By Patricia Yongue

Our scholarly scribe, Patricia Yongue, explains a period of indecision about racing at Renault, while Dale LaFollette

(vintagemotorphoto) provides the period photography.

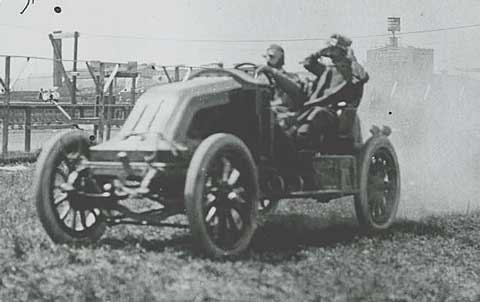

Renault driver Louis Raffolovitch passes the Allen Kingston car on his way to win the 24 hour race in Morris Park New York, September 1907. Louis Renault was not pleased.

It is somewhat ironic that, upon winning the prized driver’s and manufacturer’s awards for the 2005 Formula One GP series, Renault should announce its intention to quit F1 racing with the 2007 season (which in fact it did not) in order to concentrate on the manufacture of improved passenger vehicles.

Louis Renault racing his Renault

in the Paris- Madrid race in 1903.

Courtesy Renault.

A second F1 championship in 2006 did not produce a retraction–or did it? The irony is that a similar scenario had transpired a hundred years earlier, in 1907, when Louis Renault, fresh from victory in the French Grand Prix at Le Mans in 1906, but only a second at Dieppe in 1907, threatened to get out of racing. The business of Renault, Louis declared, was to produce passenger (i.e., touring) cars.

The Death of Marcel Renault

In 1903, the Auto Club de France had temporarily banned racing as a consequence of the disastrous Paris-Madrid race, in which eight people died and many more were injured, before the race was finally halted at Bordeaux. Louis Renault, who had himself participated in and for a time led the race, had lost his brother, Marcel, to the Paris-Madrid, and he was adamant that his works drivers resist the irresistible temptation to race. Racing was dangerous for spectators as well as for drivers, as the ACF declared and Louis thunderously repeated. At the time, there was no closed circuit racing. Road courses were open–and human, road, and mechanical vagaries too often superseded the safety measures implemented by local police and race officials.

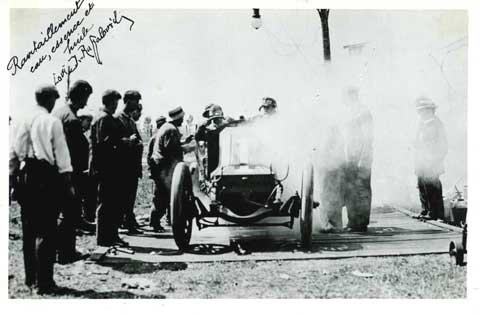

Raffolovitch leaves the pits after refreshments. New York, September 1907, Morris Park 24 hour race.

But given the highly movable object at hand and foot, the irresistible force to race prevailed. From 1905 through 1906, both France and Louis Renault consented to minimal racing and Renault, with driver Francois Szisz, won the 1906 French GP. After Szisz’s car placed second in 1907 to Felice Navarro’s Fiat, Louis, backed by Michelin, reinstated his ban. But there would be challenges and more temptation. First, Fiat had been hell-bent on upending the French in their own GP, a matter not to be taken lightly. Then, in 1907, Brooklands in England opened as the first purpose-built closed circuit racing track, to be followed in 1911, in America, by the track at Indianapolis. All countries were keen to race on the track–and to race, period. The November 1908 Grand Prize Race in Savannah, Georgia, brought Szisz and Renault to America.

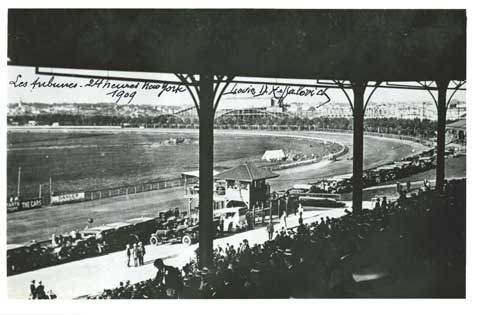

The grandstands, New York, September 1907, Morris Park.

But in 1910, irascible Louis Renault, boss at Billancourt, ordered another ban, one that would last for about fifteen years. He claimed that racing contributed nothing–Rien!–to the improvement of the automobile. Moreover, he declared that the financial and other costs of racing far exceeded revenues from whatever sales resulted from the nascent “race on Sunday, sell on Monday†market formula that was as much European as American.

Louis’ disclaimer, however, followed upon a large increase in Renault production and sales after 1906. Mais non, insisted Louis, the business of Renault was to devote all financial, human, and technical resources to developing the passenger vehicle.

But what about Louis Raffolovitch?

Needless to say, beyond the geographical boundaries of Billancourt and, in this case, the arguably myopic vision of Louis Renault, the racing of Renaults by employees was inevitable–not only because of the uncontainability of testosterone, but also because the nationalism that would define interwar competition had already begun. In America, “Renault Brothers (Renault Frères) Selling Branch,†under the leadership of brother Fernand, (who was ill of health and would die in 1909, shortly after Louis bought out his shares of the business) had welcomed the call to race as a demonstration of both the technical excellence of the marque and the skill and courage of French drivers.

Raffolovitch wrote on the photo, “Changing the tires on the detachable rims,” New York, September 1907, Morris Park.

In 1907 and 1909 in New York, on the horse racing tracks of Brighton Beach and Morris Park, Renault achieved stardom. Its greatest claims to fame were victories at the Twenty-Four Hours New York Race at Morris Park, first in September 1907, with Paul Lecroix and Maurice Bernin alternatively at the wheel of a Renault 35/45 CV, and again in September 1909, at Brighton Beach, with a schoolmate of Louis Renault, Russian born mechanic Louis Raffolovitch, taking Lacroix’ place, and the mechanic Basles taking Bernin’s place.

On this photo, Raffolovitch wrote: “I play the cavalier, alone.” He may mean he is the only one on the track at that time. New York, September 1907, Morris Park.

The material prize was $1000 and a diamond tie pin in the shape of a horse. When the overjoyed Raffolovitch improvidently cabled his friend Louis Renault with the good news, he received the following reply: “We are not amused. [We remain] behind the Michelin-Renault official ban on racing. Louis.†Raffolovitch did not let the boss’ stern disapproval destroy his victory celebration, but very soon after his few minutes of fame, he returned to his first love: auto mechanics.

Montlhery beckons

And so Renault remained stubborn. But after World War I, with the opening of the closed circuit auto race tracks in Berlin (AVUS, 1921), at Monza (1922), and at Linas-Montlhéry just outside Paris (1924), the honor of France, and of Renault itself, forced an end to Louis’ boycott. In fact, and here is another irony, Louis would soon order his troops to win world’s records, and he finally conceded that such records did help the sales of his passenger cars. (Today, by the way, we face yet another irony, as the Montlhéry Autodrome is threatened with dissolution.) In 1925, following a year of initiatory events, Montlhéry became a venue for breaking world records, at that time a dimension of constructors’ building and testing and of national chauvinism.

Raffolovitch has written in the photograph: “Refreshments–water, air, oil.” New York, September 1907, Morris Park.

Besides the fact that racing was, as we know, an

influential laboratory for passenger vehicle construction, the improved passenger vehicle influenced racing by creating a greater demand among the manufacturers that in turn motivated more competition and production, etc. Continually improved open road surfaces based on improvements to closed race tracks, especially Montlhéry, would become a salient achievement of the 1920s. Better road surfaces encouraged more car sales and continuous road building, which, for the more pastorally minded, opened up the wonders of the world to close and distance inspection, and, for the capitalistically minded, generated the establishment of new businesses and the demand for more automobiles and racing. And this time, an American living in Paris would do for Louis Renault what he could not or would not do for himself.

Acknowledgments

William Boddy, Montlhéry: The

Story of the Paris Autodrome, 1924-1960/ (London: Cassell, 1961)

Dale LaFollette, and Gilbert Hatry, Renault et la Compétition: Les folles équipées/ (Paris: Editions J.C.M.-Jean Claude MANGIN, 1985).

Did you know that Renault was the first car to run for 24 hours at an average speed of over 100 mph? And it did so due to the the amazing yet unheralded efforts of an American in Paris! Patricia Yongue tells the story in an upcoming edition of VeloceToday.

Dear Patricia Yongue,

I read your article with interest and I note some mistakes.

First of all, the french driver was RAFFALOVICH and not RAFFOLOVITCH.

About the pictures

– The picture of the Renault #129 in Paris-Madrid 1903 was driven by Grus and not by Louis Renault (#3 in this race).

– The six pictures of Raffalovich are about the 24 hours race at Brighton Beach in 1909 and not at Morris Park 1907. (in the thrid picture, you can see the year writing on…)

– In the caption of the picture 5, you wrote “(…)“I play the cavalier, alone.†He may mean he is the only one on the track at that time. (…)”, not exactly : “faire cavalier seul” mean that you lead the race easily without rivals.

Same with the picture 6, the correct translation is “Refreshments–water, gasoline and oil.”

About the text

– The Indianapolis Motor Speedway was built in 1909… 1911 was the year of the first most famous “International 500-Mile Sweepstakes”,

later call “Indy 500”.

– The 24hrs at Brighton Beach was held the 27th and 28th august 1909, not in september.

Hope to be useful…

Regards

Jean-Yves Lassaux

Paris – France

References:

– “The New York Times”, August 29, 1909, Sporting News, page S1.

– “A Record of Motosport – Racing before WWI”, Darren Galpin, page 520.

– “Chroniques du sport automobile mondial”, vol.2, 1907-1914, J-P Delsaux, 2007.

– And more… 😉