Three generations of Renault record breakers on the concrete oval of Montlhéry. From left to right: the 1956 Etoile Filante turbine car, the 1934 Nervasport a and the 1926, 40 CV Spéciale Type NM .

(photo Renault Communication).

By Gijsbert Paul Berk

Recently Renault invited a number of automotive journalists to the famous Montlhéry race track south of Paris for a demonstration of a number of their classic competition cars. Officially it was to commemorate that the French company has been over 115 years actively involved in motor racing, record breaking and rallying. But it also proved to be an unique opportunity to see and hear these wonderful machines in action.

However, some surmised that the real objective of this PR operation was that Renault wanted to boost its image as a maker of successful competition cars. One of the reasons is that the French automaker has the ambition to make a full come back in the F1 championship with its own team and not merely as an engine supplier.

In 2015 Carlos Ghosn, Chairman and CEO of the Renault Nissan Group, already had explained why: “Because despite winning multiple world championships as a supplier to the Red Bull ream, the payback in public awareness has proved to be very limited”. Read The Silent Champion

In December last year Renault bought Team Lotus, which like Red Bull uses Renault engines. However, during last year’s season, the newly designed Renault Grand Prix engines lacked in performance and reliability. And it looked as if the plans were shelved.

But the Renault F 1 engines have been fully developed and are now proving to be winners. Plus, the financial results of the company show sound progress. Perhaps the right moment to join the F1 circus again is not too far away.

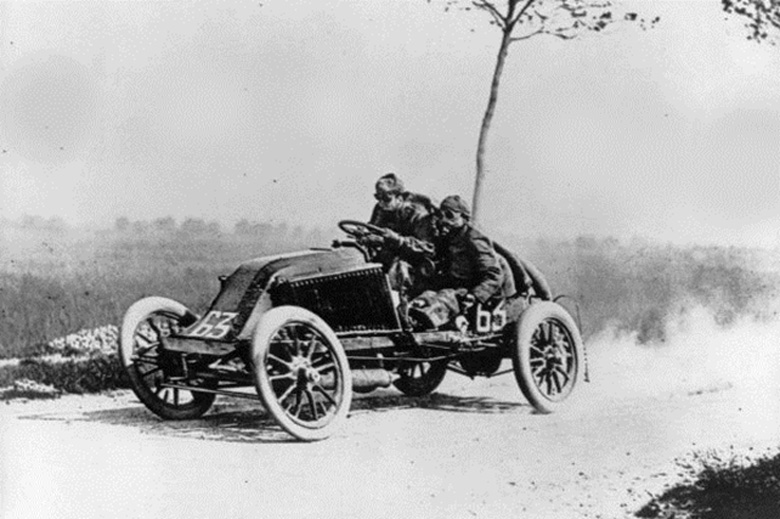

In fact, Renaults racing successes began 117 years ago. In 1899 Marcel Renault, brother and business partner of company founder Louis Renault, won the Paris-Trouville, a city-to-city race over public roads. In France in those days such races were often sponsored by the leading newspapers and magazines and thus created much media attention. Therefore, competing in them was an excellent way for car makers such as the Renault brothers to demonstrate the performance and reliability of their products. In 1900, a year after the Paris-Trouville victory, Marcel together with his brother Louis, won the light car category of the Paris-Toulouse-Paris race, over a distance of 1448 km. Their first international success came in 1902 when Marcel Renault, with his riding-mechanic Rene Vauthier, won the Paris-Vienna race, driving the Renault Type K pictured above.

Unfortunately, the 1903 Paris-Madrid race ended in a tragedy. Blinded by the dust cloud from a preceding competitor Marcel missed a curve; at high speed his car went off the road and ended in a ditch. Vauthier was thrown clear and survived. albeit with serious fractures. But Marcel Renault died from his injuries within 48 hours after the accident. After the tragic accident of his brother, Louis Renault swore that he would never again participate in a racing event. But when the French automobile club announced their decision to organize a Grand Prix on a closed circuit he changed his mind.

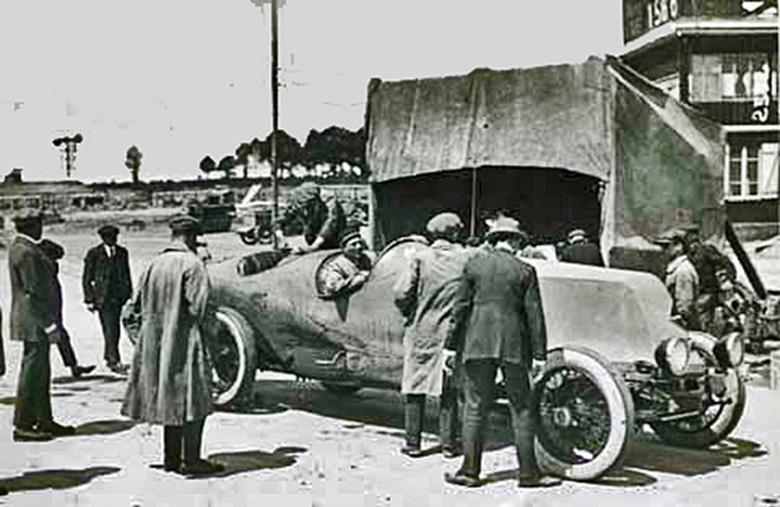

The 1906 Renault 90 CV AK has an important place in the sporting history of the car manufacturer from Billancourt. On June 27, 1906 Ferenc Szisz (born in Hungary) drove it to victory in the French Grand Prix, with an average speed of 101.195 km/h (62.880 mph), beating the famous Italian driver Felice Nazzaro, who with his Fiat Corsa, came in second. Albert Clément driving a Clément-Bayard was third. When Szisz drove his Renault over the finish line he had covered 1,238.16 km in just 12 hours and 15 minutes.

The race, as the French called it, “le Grand Prix de l’Automobile Club de France”, took place near the town of Le Mans – today well known for the 24 hour races. The circuit consisted of a triangle of public roads, with a total lengths of 103.18 km (64.113 miles). For the occasion these roads were closed to normal traffic. The event was held over two days. Six laps on the first day, followed by an overnight rest and six laps the second day.

According to old race reports the blacktop tar (bitumen), used to cover the earth road surface, melted on parts of the circuit exposed to the heat of the midday sun and this made the track very slippery. The competitors also suffered many tires failures. But Szizs’ Renault was equipped with the latest invention by Michelin; tires that were mounted on detachable rims, which made tire changes much easier and faster. The design of the 1906 Grand Prix Renault was in those days quite conventional, with a front mounted engine and rear- wheel drive, a ladder frame chassis with leaf springs all-round and a three speed gearbox. Its six cylinder engine has a cubic capacity of 14.85 liters and the cooling radiator was situated at the rear of the engine block, a solution that Renault till the mid-thirties also used for his production cars.

In the early nineteen twenties Alexander Lambin, a French industrialist, commissioned the architect and engineer René Janin to build a motor racing circuit in the Essonne Department, about thirty kilometers south of Paris. The Autodrome de Linas-Montlhéry, with its banked oval shaped track measuring 2.55 kilometers (1.58 miles), was designed to accommodate cars up to 1,000 kg (2,205 lb.) to drive at 220 km/h (140 mph). Later the so called ‘circuit routier’ was added. In many aspects Montlhéry resembled the Brooklands motor racing circuit, which had existed since 1907 near Weybridge in Surrey, UK.

Even before the inaugural Grand Prix de l’ACF on July 26, 1925, many leading French car manufacturers queued to use Montlhéry for speed and endurance records. Of course Renault was one of them. From the point of view of the industry the ambition to establish such records is easy to understand. In those days there was no global TV audience. Media coverage was mainly limited to newspapers and motoring journals and in some cases local radio. Racing cars and record machines generally used the same components and the development costs of both were largely comparable. But contrary to participating in races setting up a record attempt involves less risk for image damage. The factor ‘luck’ is limited, because your cars do not compete with a number of other cars and drivers but only with the stopwatch. So, when your car establishes a record, the resulting publicity spin-off is assured. But if you do not succeed only a few will know about it.

On May 11, 1925, the American born engineer Ellery (Alain) Garfield and Robert Plessier, both engaged by Renault, scored their first ‘world’ records at Montlhéry; over 500 km and 500 miles. The car; a Renault 40 CV, Type ML had a special open torpedo body without mudguards. They returned to the track gain on June 3 and 4, to cover 3,384.759 km in 24 hours. Their fastest lap was timed at 178.475 km/h, and their average was 141.331 km/h, This included the stops for taking petrol, checking and topping up oil and water and changing more than 100 tires during those two days.

But their record did not stand for long and Renault decided to build a faster car. The 40 CV was their flagship model and needed to demonstrate its speed and stamina in view of the fierce commercial competition in its market segment.

The ‘new’ Renault 40 CV Type NM record car was based on the short ‘sports’ chassis. The narrow single seater coupé coachwork has a more or less aerodynamic shape. Its construction used the Weymann System, with a frame of thin wooden rafters covered with leather cloth. However, the bonnet and cowl were metal. The front mounted 9.12 liter six-in-line engine drove the rear-wheels through a 3 speed gearbox. The water radiator was still mounted at the rear of the engine but the cooling air came in from the nose. To reduce the weight to a minimum the front-wheel brakes were abolished.

While the car was being build a team of mechanics was trained to reduce the times of the pit stops. Everyone was taught a specific task (14 altogether) and this paid off. The petrol tank contained 110 liters and had to be filled with a hand pump. Teams of two men each were able to change a wheel within 50 seconds, while the others checked oil and water.

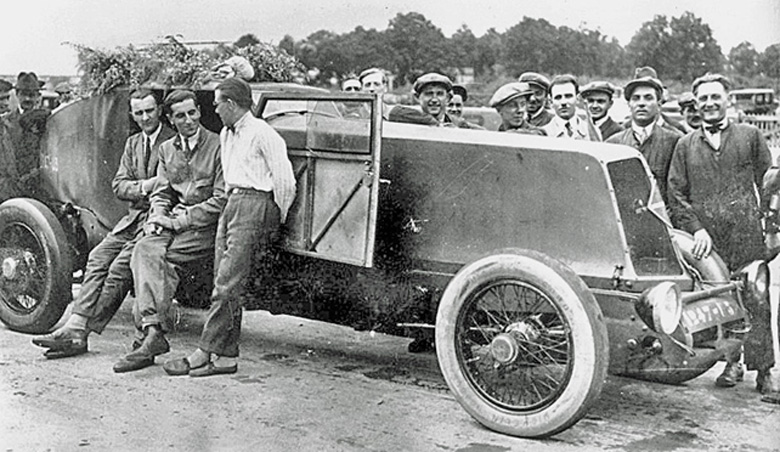

Montlhéry, July 10, 1926 Guillon, Plessier, Garfield and their team of mechanics after the successful record attempt.

(photo Renault Communication).

On February 23, 1926 Garfield drove the 40 CV Type NM over a distance of 100 km in 31 minutes 46 seconds, which comes down to an average speed of 188.867 km/h and meant a new record. On March 19, covering 536,659 km in 3 hours, another record was broken. Then on July 9 and 10, Garfield, Plessier and a third driver by the name of Paul Guillon went for the 24 hours’ record. In those two days they covered a distance of 4,167.578 km at an average speed of 173.649 km/h. During this run they also bettered the existing records for 500 and 4000 km, and those for 1000 and 2000 miles.

The car recently presented at Montlhéry was not the actual 40 CV Type NM Record beater, which does not exist anymore. It is an exact reconstruction build in 1969 by a team of engineers and mechanics for the car museum at Clères (near Rouen) and was later bought by the Renault company.

The 1906 GP de l’ACF Renault was powered by a 13 litre four cylinder engine.Great article as usual by Gijsbert Paul,keep up the good work!

Michel Van Peel

Sadly Ellery Irving GARFIELD’s name is misspelled as “GARDFIELD” on the Pichon build replica of the Montlhéry 1926 40 cv record car that the Société d’Histoire du Groupe Renault keeps in their collection. Ellery Garfield was an American by birth (July 25, 1893 Salem-Boston, USA), who started working for Renault in 1916. After a first interreption from 1919 to 1922, he was re-employed by Renault, and again after a second interruption between 1926 and 1929. On July 11, 1930 he was killed in practise for the Tourist Trophy, near Belfast in a Renault.

One of those early GP Renaults, built I think in 1907, is owned by Kirk Gibson, who lives in Pennsylvania. His father was a major collector of early cars. The Renault was discovered being used as a track service vehicle at Seekonk Speedway, in southern Massachusetts. So it’s been in Kirk’s family since perhaps the 1930s. Maybe we can talk Kirk into taking us for rides in it next summer, for a VT feature?