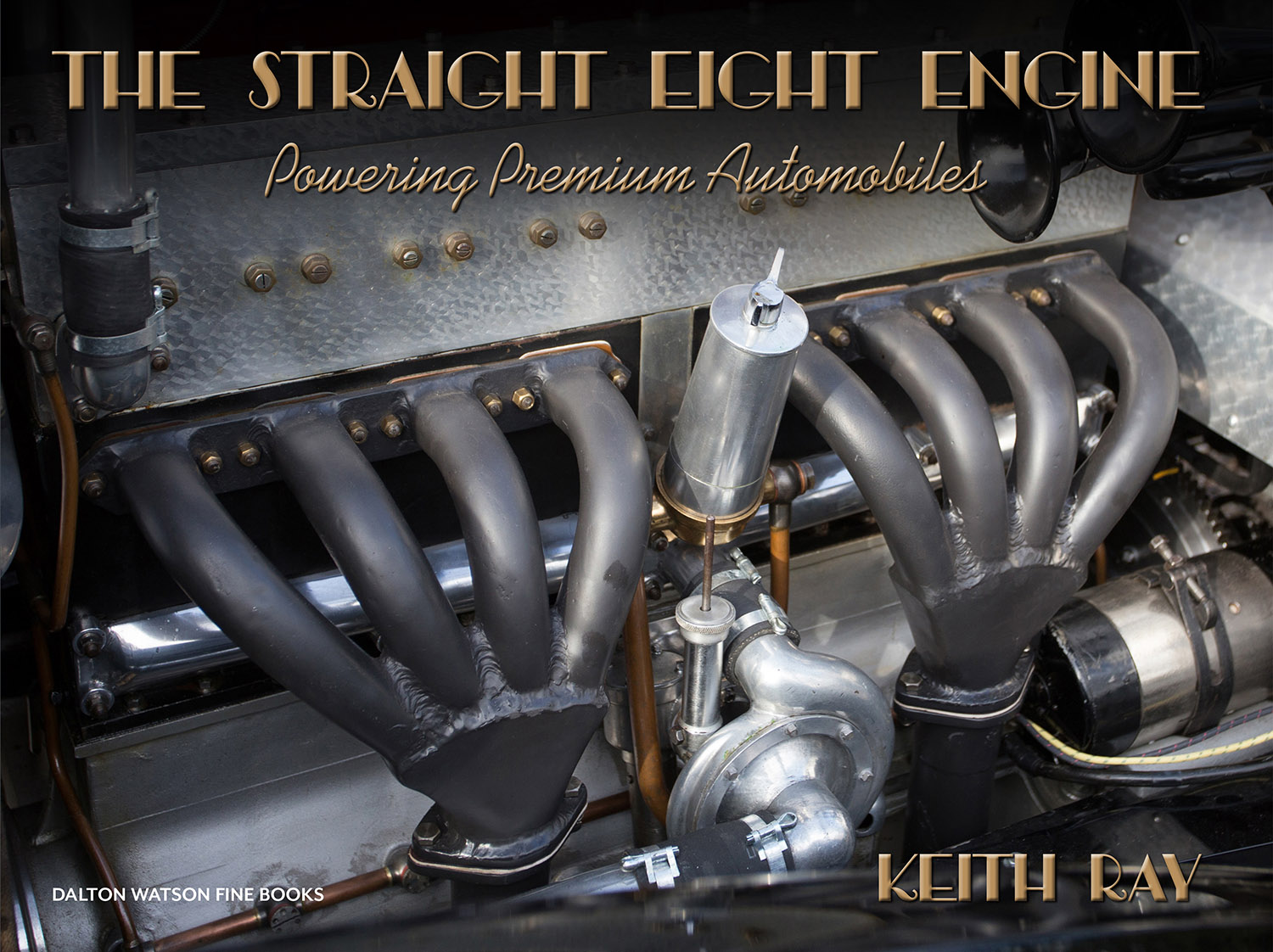

The Straight Eight Engine

By Keith Ray

Dalton Watson, October 2020

ISBN 978-1-85443-306-0

Landscape format, 219 mm by 290 mm

Hardcover, 404 pages, 479 photos, dustjacket

Price $95

See pages and table of contents

Review by Pete Vack

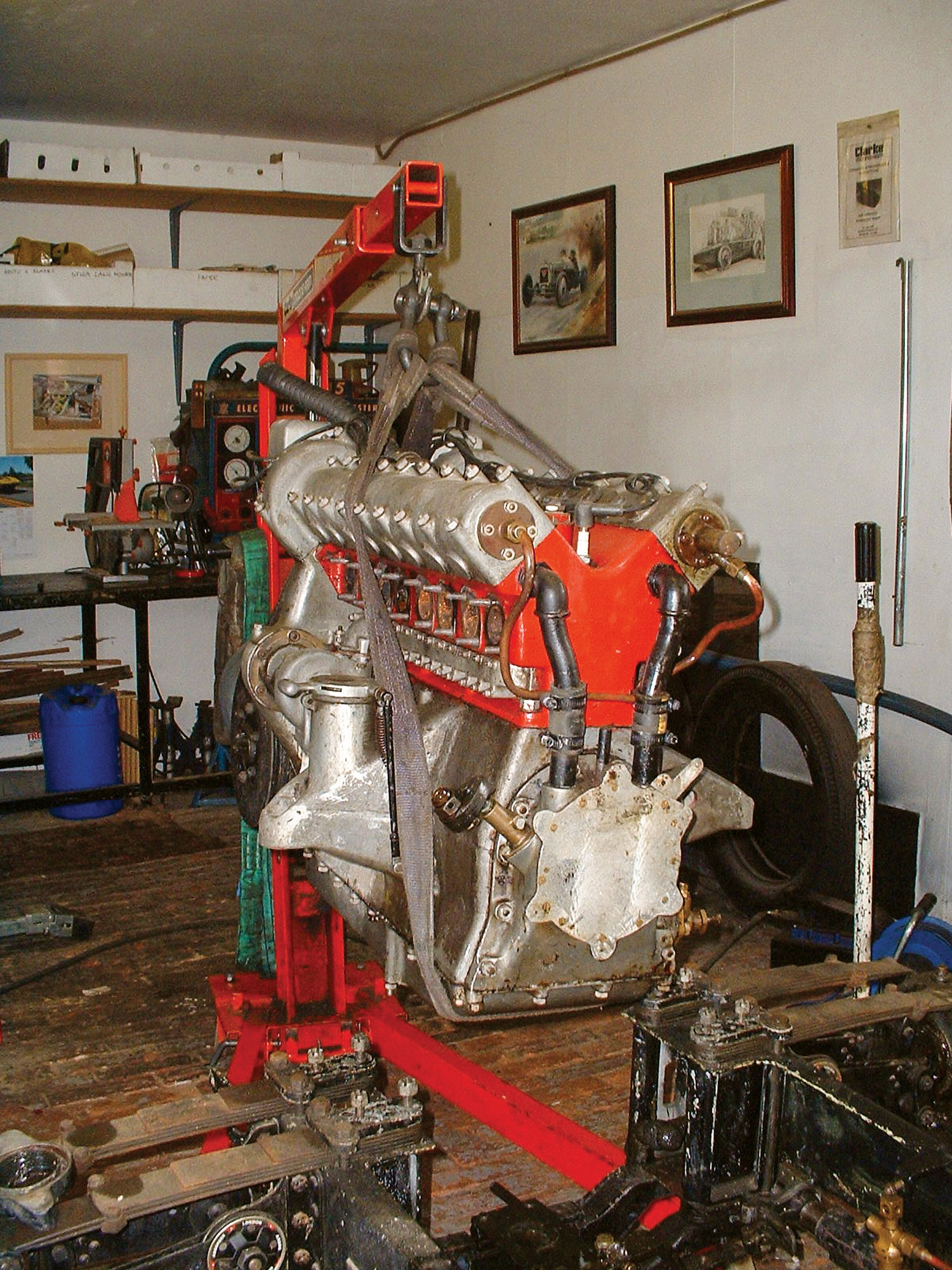

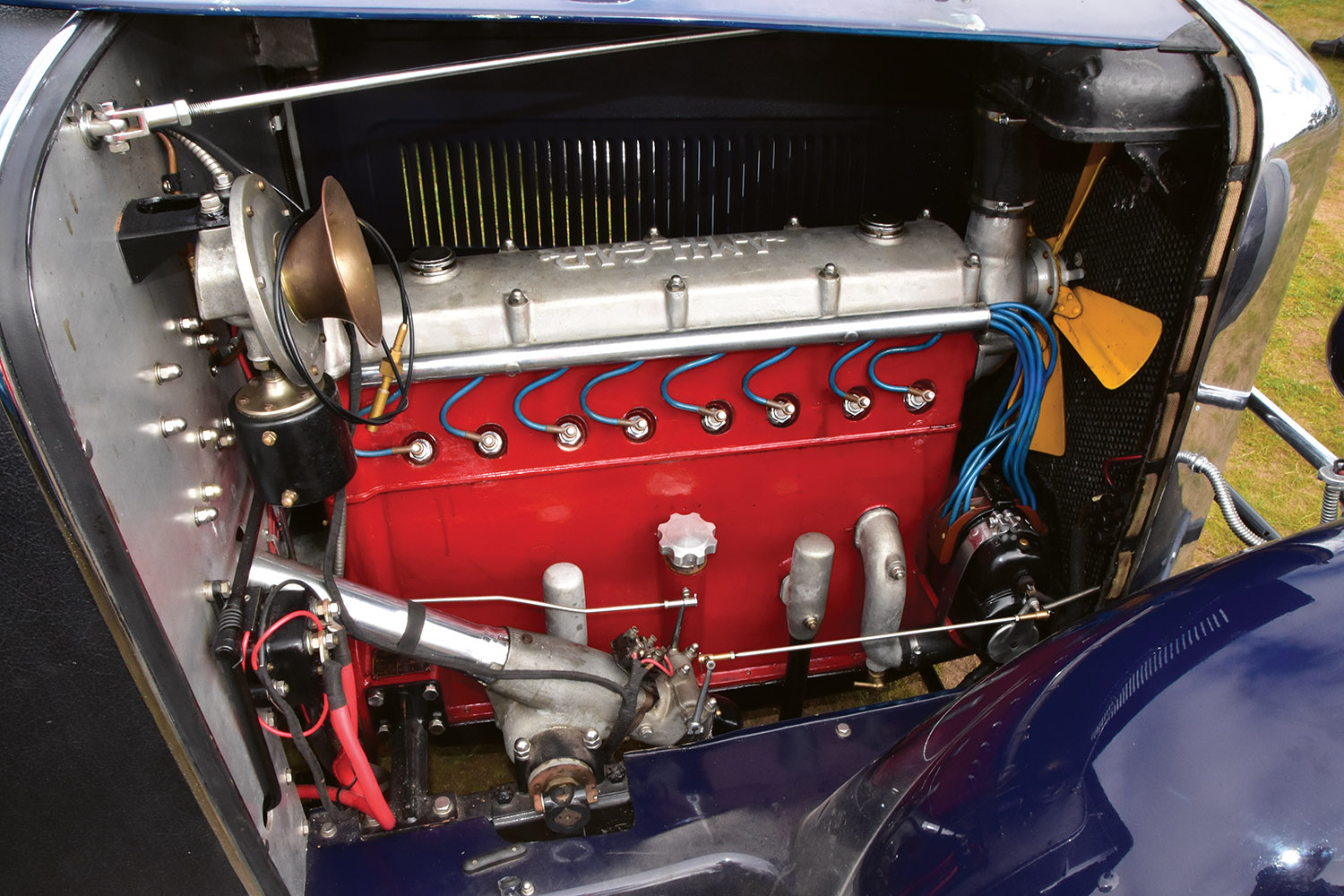

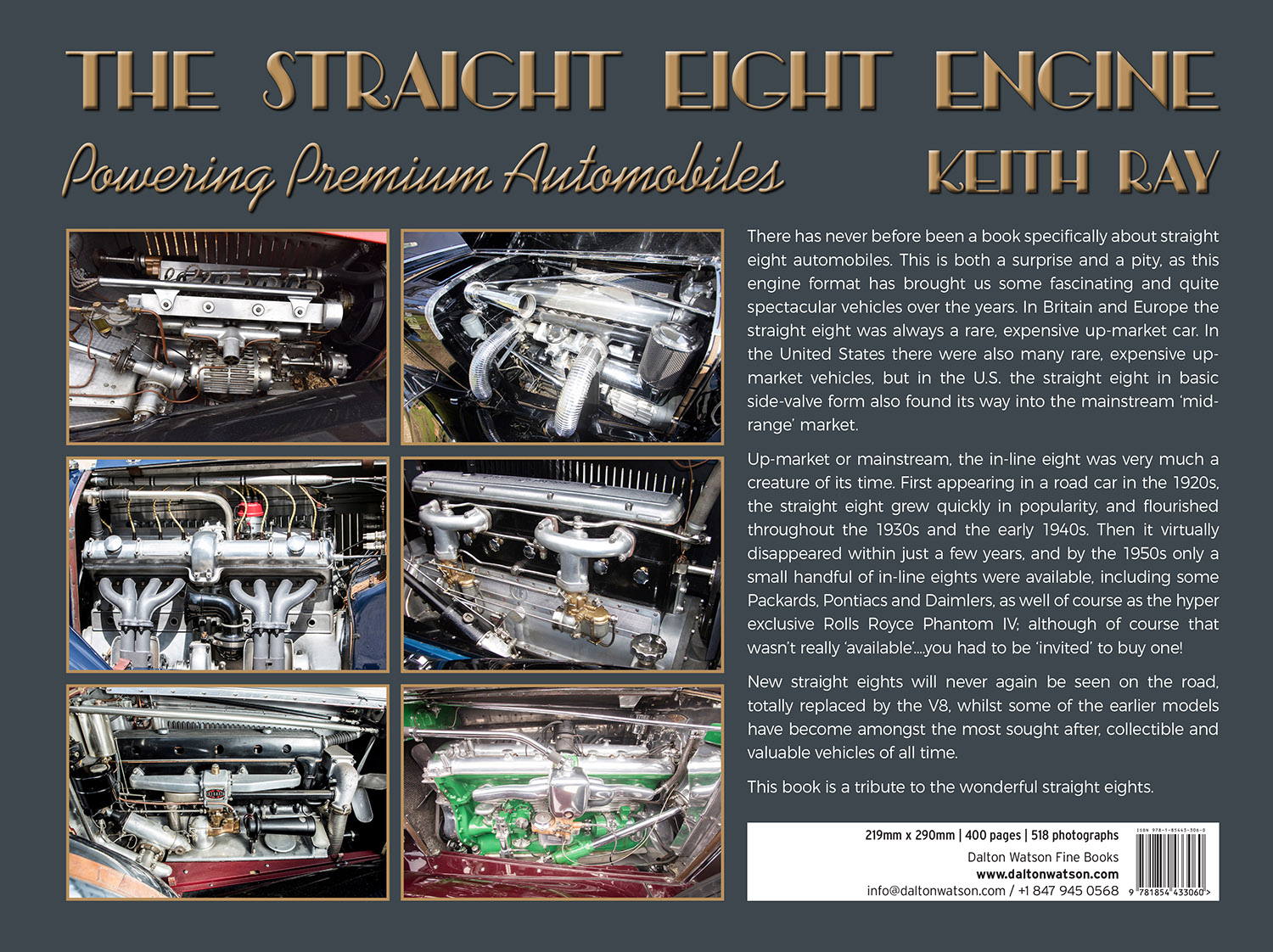

Keith Ray’s new book The Straight Eight Engine is a diverse and interesting read, bursting with color photos and welcome information. It covers everything from a rare Alvis to the very common Buick your uncle used to drive.

Ray, who lives in the U.K., found his passion early on while learning about Bugattis from the Observer’s Book of Automobiles. About eight years ago, he met Bryan Tyrrell, a member of the Railton Owner’s Club, and the two discussed the idea of writing a book on straight eights, like the Hudson that powered the Railton.

Years later after tons of research, Ray had found enough fascinating information and photos to proceed. Did you know that there were at least 92 manufacturers that made use of the longest engine ever installed in a car?* And of those approximately 92 manufacturers, 43 were manufactured in the U.S., 19 in the U.K., 11 in France, 7 in Italy and 6 in Germany. The long eight continued after WWII for a few years, but the glory days were during the 20s and 30s as designers looked for power delivered smoothly and quietly.

The U.S. variety were mostly rather pedestrian units, using flat head or side valve intake arrangements. But on top of the heap in any country was the Duesenberg Model J that rivaled the best Europe could offer. The author doesn’t leave out those lesser units meant to power Pontiacs and Buicks though, nor is the Alfa and Bugatti contingent forgotten.

In a series of short chapters at the beginning of the book, Ray explains why so many used the layout, and the technical advantages and disadvantages of the straight eight.

Why a straight eight anyway? Why didn’t the V8 take hold instead? Surprisingly, according to Ray, a lot has to do with the limitations of chassis design and steering; “In cars with a chassis frame that had to be narrow at the front to allow a reasonable steering lock with semi-elliptic suspension, there was limited room width for a vee-engine.” In addition, the current style called for long hoods, so the extra length of the eight was also desirable. Finally, Alfas and Bugattis were tearing up the racetracks with their high power straight eights and that, of course, was status.

So why not a short stroke eight? Ray answers this as well. Though it was fine to have a long eight, if the bores were large, it would add considerable weight and length to an already lengthy affair. And the required long stroke resulted in a machine that was flexible with high torque. “The flexibility also allowed smooth running at low speeds, which suited the upper part of the market where many of the more expensive cars would be chauffeur driven.”

Ray devotes a chapter to explain the limitations of the straight eight and why it eventually was displaced by the V8. Six areas of deficiencies in design such as torsional vibrations, carburation, and inlet and exhaust design all interact, “…and in reality, nearly all straight eight engine designs are a big compromise.” As long as the revs were kept low – below 4000 rpm – straight eights were manageable. But in the end, the V8 had fewer design constraints, and the advent of the independent front suspension and unit chassis favored the V configuration.

Straight eights were also found in the air and on waterborne craft, and Ray devotes a chapter to describing those efforts, along with a section of advertisements featuring straight eight automobiles.

Alvis went out on a limb with a DOHC straight eight incorporating front wheel drive for the 1927 Grand Prix season.

In most cases there are great color photos of the engines, but there are a few chapters which address the cars without photos. Still, it is remarkably complete and we found photos of the Alvis and eight cylinder Amilcar worthy of note. In 1926 Alvis designed and built a Grand Prix straight eight with horizontal opposing valves. He provides photos for this, as well as the more conventional 90 degree DOHC that quickly replaced it. Neither were successful, but as the DOHC engine was not familiar to this reviewer, we dug out Borgeson’s Classic Twin Cam Engine to see if we had missed something. Alas, it was Borgeson who failed to mention the Alvis DOHC, while Ray didn’t catch the last Grand Prix Gordini of 1955-56, but Ray admits there may have been a few that slipped through the cracks. Another rare DOHC eight was attributed to the Rally. As it was not certain if Rally’s DOHC straight eight of 1927 was a prototype or actually in production, this one is a bit of a mystery. Ray got the specs, but no photos, Georgeano listed a DOHC straight eight as a prototype and Borgeson ignored the marque entirely.

The book covers almost every manufacturer of straight eight models alphabetically; the author found 92 and there is a chapter for each. Our readers, rest assured, are more than familiar with Alfa and Bugatti eights, (multiple pages are devoted to both with excellent color photos) but we found an interesting selection of lesser know straight eight Italian and French engines to examine.

Amilcar

Known for its voiturettes, in 1928 Amilcar introduced two eight-cylinder models, called the 11CV and the 13CV, the first with a 1980 cc engine, the latter with a 2326 cc unit. Both featured a SOHC head with two valves per cylinder. Ray had to search to find a photo of a 13CV, but finally found one in the famous “Baillon Barn Find” collection.

Known for its voiturettes, in 1928 Amilcar introduced two eight-cylinder models, called the 11CV and the 13CV, the first with a 1980 cc engine, the latter with a 2326 cc unit. Both featured a SOHC head with two valves per cylinder. Ray had to search to find a photo of a 13CV, but finally found one in the famous “Baillon Barn Find” collection.

Ferrari’s First Straight Eight

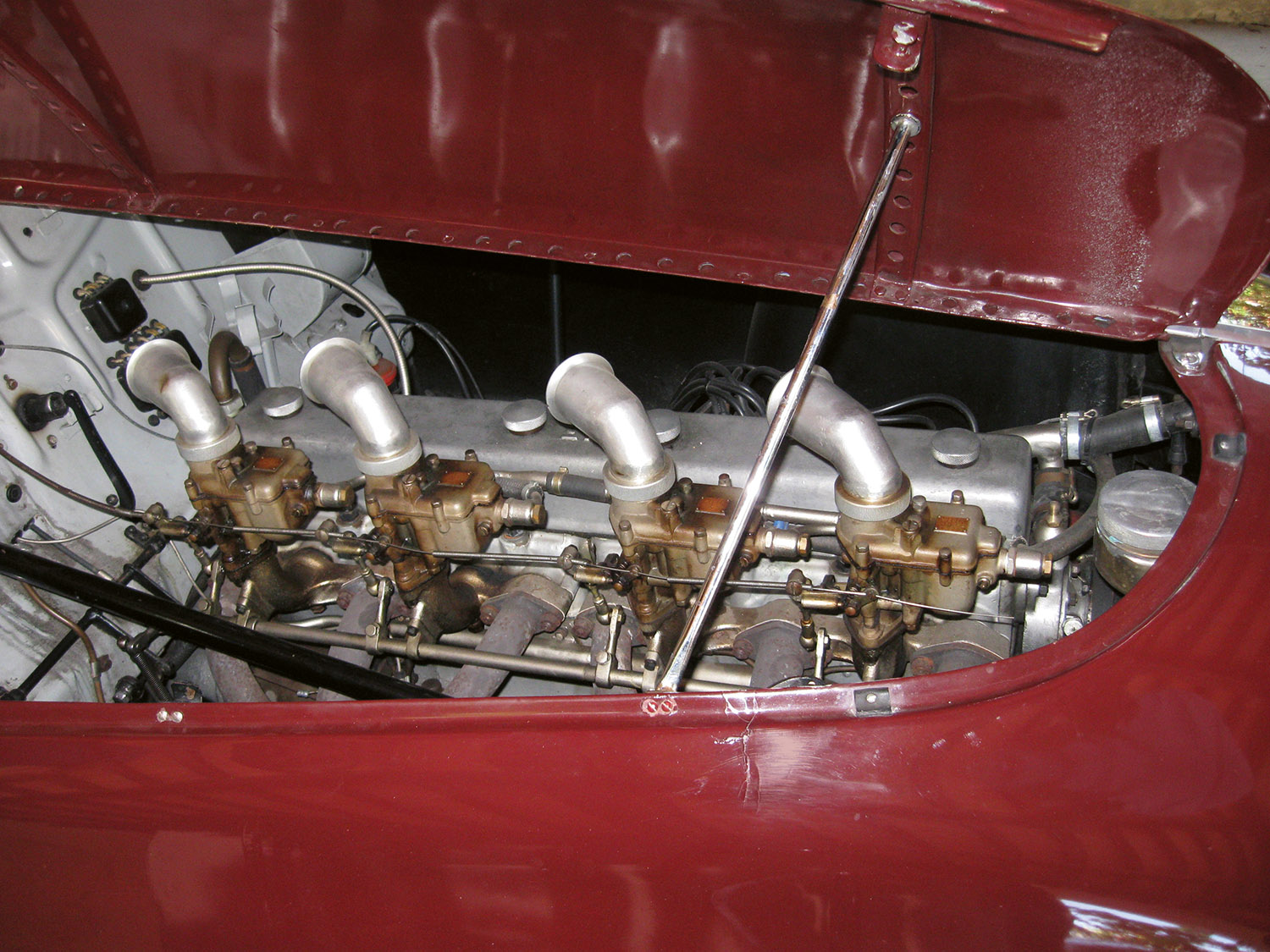

And last of course. The Auto Avion 815 used two Fiat Balilla 508 1100 ccc blocks connected with an alloy crankcase with five main bearings. Ray notes that it used four downdraft Webers, making the intake more evenly distributed but required some careful balancing.

Isotta Fraschini

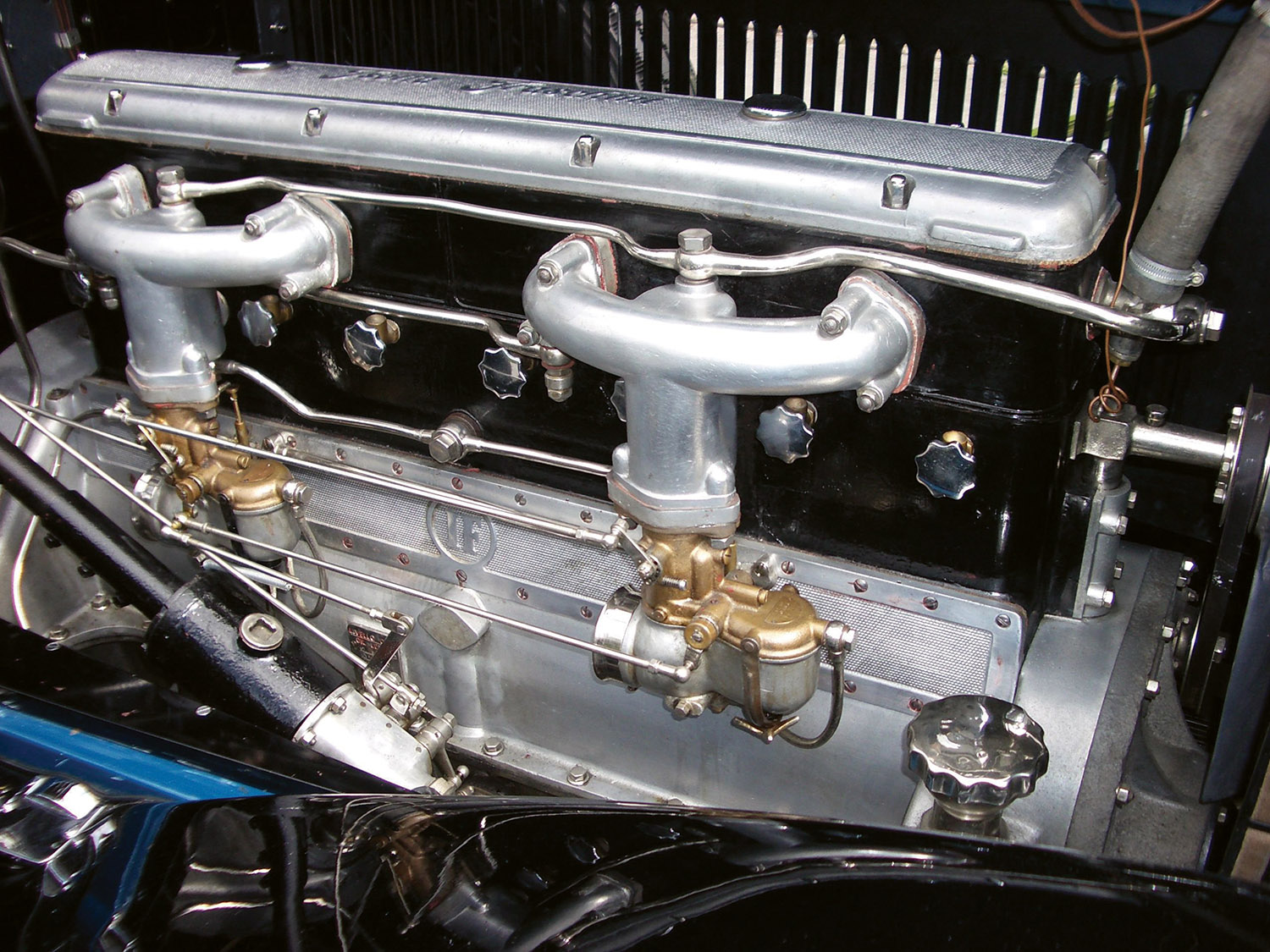

VeloceToday has never done much on this marque; readers, historians, let’s fix that. In the meantime, Ray reminds us that I-F 8A had no intake manifold, but two ‘stub’ carburetor mountings feeding an internal passageway to the cylinders. According to Wiki, in 1919, I-F was the first to introduce a straight eight in a production model.

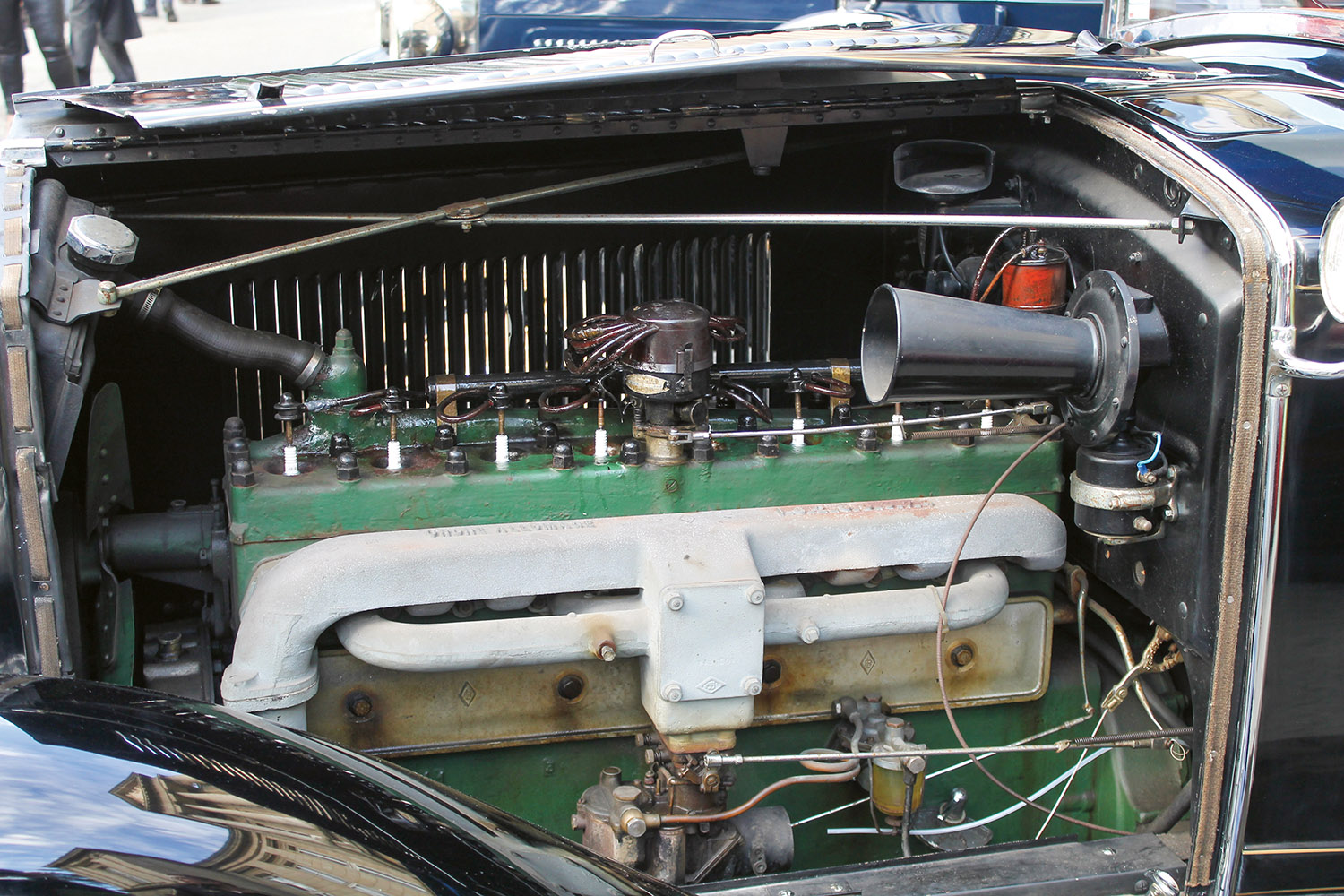

Renault

Easy to forget that the high-end Renaults of the thirties were straight eights including the Reinstella, Nervastella, and Suprastella models all with sidevalve heads and significant displacements over 4 liters. Before 1929, Renaults were mainly six-cylinder affairs and after the War, four cylinders. Pictured above is the unit in a Nervastella model.

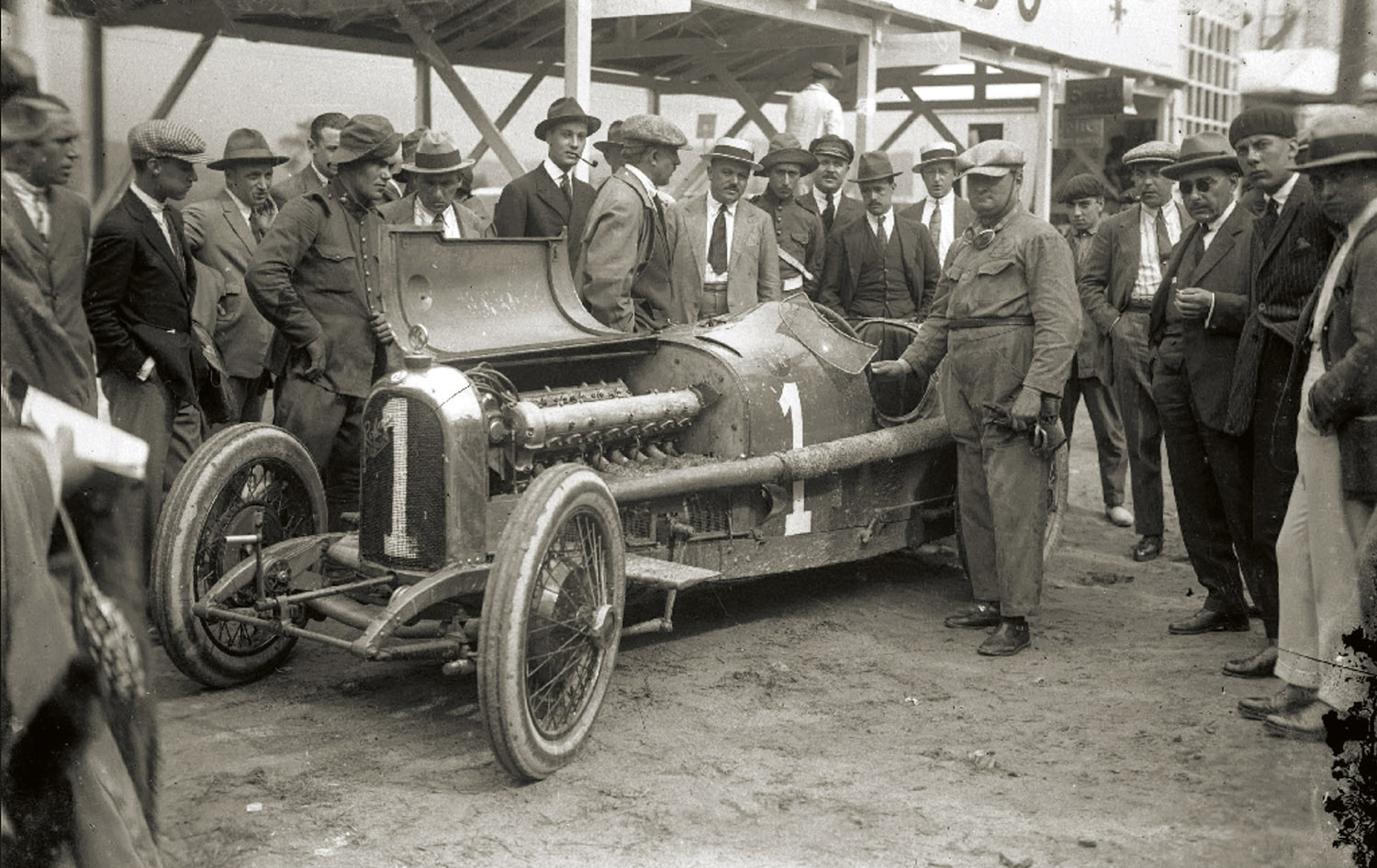

Rolland Pilain

One of the most advanced eights of the 1922 Grand Prix season was built by Rolland Pilain, with a thirteen-piece crankshaft, five main bearings, roller bearings for the con rods, magnesium pistons and one design with desmodromic valves. It was not a success and photos are rare.

Bottom line: We enjoyed this book. Not quite Ludvigsen’s The V12 Engine but an excellent value. The lack of an index is not the norm for Dalton Watson but alleviated by light chapters arranged in alphabetical order by car. Great layout, reasonable price and a welcome addition to the library.

*Exceptions are Voisin’s straight twelve of 1934, and Packard reportedly built a straight twelve prototype.

an early ’54 Packard catalog called their engine the most highly developed straight eight in the world. the Bugatti club took ’em up on that, and their next catalog omitted the phrase and substituted a cross section drawing of the combustion chamber. although my mother’s Caribbean had an aluminum head with 8.7 compression–the highest in ’54–I bought an offenhauser finned aluminum head for it, which had a differently shaped combustion chamber. of course it felt peppier after the change but I never did a comparison test, darn it. when we sold it to a local collector he put the original head back on!