By Clyde Berryman

A large wooded area on the western edge of Paris played a crucial role in jump-starting motor racing on the European continent after World War ll, exactly 70 years ago this week. Clyde Berryman sums up the racing history of the famous Bois de Boulogne park in Paris, and takes us on a park visit not quite like any other. Part 2 will cover the 1946 event, and Part 3 will focus on the last few races in the Parisian park

In August 1945, the mushroom clouds of atom bombs, and neat rows of white-clad sailors lining the decks of the battleship USS Missouri for VJ-Day in Tokyo Bay were the dramatic images coming from the other side of the globe. Smoke still rose from the rubble of German cities pounded into oblivion by massive strategic bombing. Adolf Hitler had committed suicide in his Berlin bunker as recently as May 1945. The most cataclysmic war in history had come to an end, leaving national economies destroyed, and entire populations ravaged, displaced, and distraught. Seemingly, it was no time for a motor race.

In August 1945, the mushroom clouds of atom bombs, and neat rows of white-clad sailors lining the decks of the battleship USS Missouri for VJ-Day in Tokyo Bay were the dramatic images coming from the other side of the globe. Smoke still rose from the rubble of German cities pounded into oblivion by massive strategic bombing. Adolf Hitler had committed suicide in his Berlin bunker as recently as May 1945. The most cataclysmic war in history had come to an end, leaving national economies destroyed, and entire populations ravaged, displaced, and distraught. Seemingly, it was no time for a motor race.

However, the city of Paris was spared much of the physical devastation endured by other cities of its size and importance, mainly due to the German “Blitzkrieg” defeat of France in May-June 1940. Its citizens had endured four long years of Nazi occupation, but the city of lights was saved a second time when the German garrison commander, General Dietrich von Choltitz, mercifully disobeyed Hitler’s orders when asked, “Is Paris burning?” French General Leclerc’s “2e DB” armored division was given the honor of leading the Allied armies into the city from the Porte d’Orleans, coming home to an emotional hero’s welcome in late August 1945 (while Ernest Hemingway and friends busied themselves liberating the bar of the Ritz!). After the war, Paris rapidly found its way back to its zesty pre-war lifestyle. Maurice Chevalier, Charles Trenet, and Edith Piaf famously led the way.

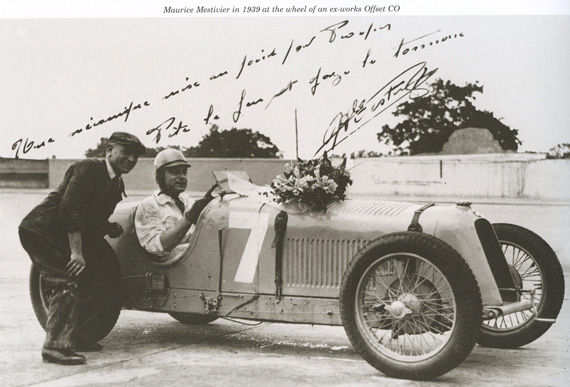

By contrast, a modest man named Maurice Mestivier remains to this day a forgotten footnote even in the automobile world. Few know that it was largely through his efforts that motor sport in Europe made its first comeback from the war. A privateer amateur driver, Maurice’s greatest day of glory had taken place ten years earlier on May 26, 1935.

The Circuit d’Orleans was a 25-lap voiturette race on a short street circuit along the banks of the great Loire River city. Spanish driver Genaro Leoz-Abad took the lead at the start in his Bugatti T 37, but Maurice very soon got the better of him in his aging 1100cc Amilcar and amazingly, went on to defeat all the other 1500cc entrants that day!

He bravely raced his little Amilcar right up to the eve of World War ll, but his best result after that win at Orleans would only be a fourth place on the beach at La Baule in 1938. On September 3, 1939, Tazio Nuvolari crossed the finish line first in the politically uneasy Yugoslav Grand Prix run around Kalemagdan Park, Belgrade, just three days after German troops had stormed into Poland. This marked the premature end of the 1939 season and of all international motor racing for the next six years.

Now in May-June 1945, Mestivier, aided by an even more obscure colleague named Picard, worked feverishly with the A.G.A.C.I., the Groupement National des Refractaires et Maquisards (a war veteran group), and the Automobile Club de I’lle de France, to resurrect the sport with a series of three races to take place in the Bois de Boulogne on a single day: 9 September, 1945.

Considering that motor racing did not resume in Great Britain until June 1946 (a field of eight drivers showed up for a three-lap event called the Gransden Lodge Trophy organized by the Cambridge University automobile club around an abandoned airfield), Mestivier’s achievement so soon after the close of the war was a real “tour de force.”

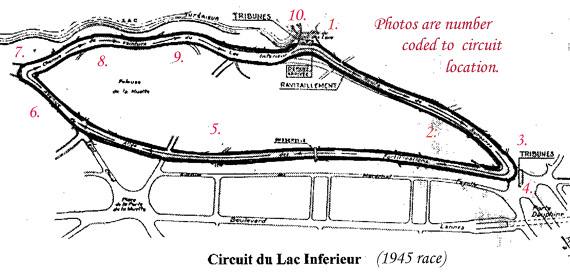

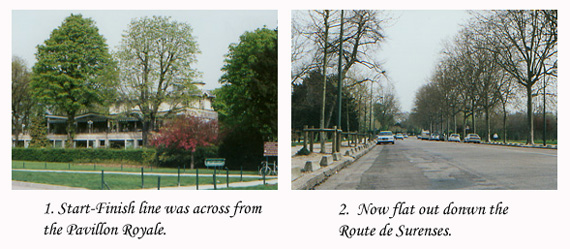

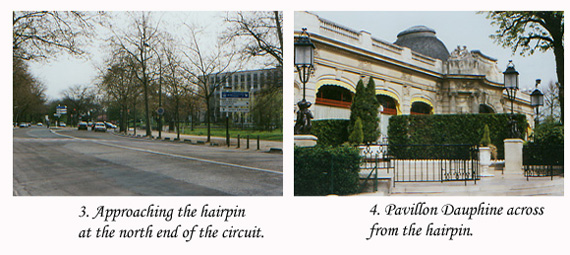

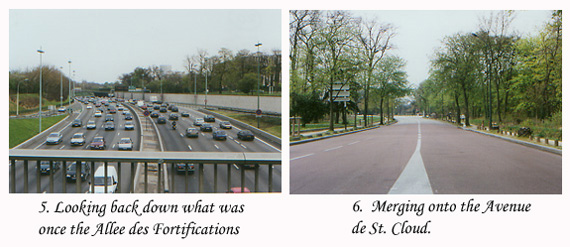

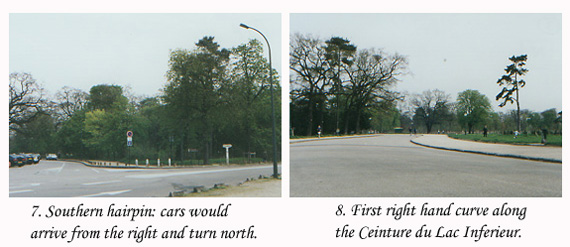

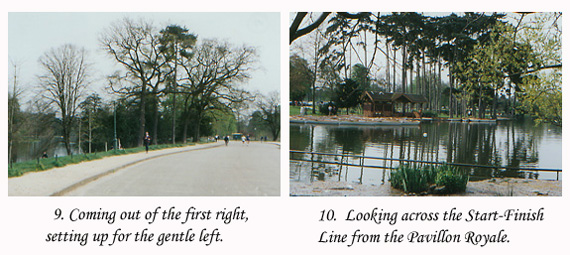

An oblong-shaped 1.99 mile track was marked out in the Bois for the day of the races. It reached from a point southwest of the Porte de la Muette up to the Porte Dauphine, making use of the principal alleyways and roads in the park between the artificial Lac Inferieur and the edge of the city. The Start/Finish line was at an intersection at the northern tip of the lake, just in front of the Pavillon Royal. The pits were set up on the inside of the circuit just beyond the start line along the Route de Suresnes which was a broad tree-lined avenue leading straight to Porte Dauphine. A grandstand was erected opposite the hairpin turn, formed at this north end of the track and no doubt, the more fortunate spectators could watch the cars approaching from the posh Pavillon Dauphine located on the left side of the road. The drivers would then veer sharply right around this hairpin to plunge down the Allee des Fortifications, a long stretch of road which ran parallel to the apartment buildings of the well-heeled residents of the 16th Arrondissement of Paris, and on down past the Place de la Porte de la Muette.

Today, this is the part of the original circuit which has disappeared entirely, having been swallowed up by the modern eight-wide asphalted lanes of “Le Peripherique,” the circular Paris beltway which travels through underpasses with exit ramps at both the Portes Dauphine and La Muette.

Back then, the Allee des Fortifications joined the Avenue de St. Cloud, which swung gently to the right, and brought the cars to the southern hairpin of the circuit, marked out by those proverbial straw bales. After another sharp second-gear corner, the cars would negotiate the loping right-left-right curves of the Ceinture du Lac Inferieur back to the Start/Finish. Although the Bois had changed enormously since 1945, this is the portion of the circuit which probably has been the least affected. One is immediately struck by both its narrowness, and how it is remarkably flat with no camber at all in any of the curves. Certainly, any jostling between cars here could have easily projected a competitor toward the outside of the track through rows of spectators, and down the sloping grassy lawn into the waters of Lac Inferieur!

Stroll through the Bois today and it is doubtful you will come across anything which will make you remotely aware that motor racing once took place in the park. This is not Reims or even Rouen ,where until a few years ago the dilapidated remains of pits and grandstands still recalled the ghosts of the past. There is a small stone building looking rather abandoned at the southern edge of the Pelouse de la Muette, the only remaining structure in sight with perhaps the right vintage to have been around in 1945.

A memorial to Jean-Pierre Wimille was subsequently built at Porte Dauphine. Good luck to those who can find it today: Five anodyne blocks of concrete with the bronze medallion turned-green of Jean-Pierre in profile with his soft racing headgear. His life dates are beneath with no further explanation. There’s also the usual graffiti which curses everything today. It sits forlornly on the north side of the “rond-point” of Porte Dauphine, visible to anyone who happens to glance in the right direction from the ramp to “Le Peripherique.”

A memorial to Jean-Pierre Wimille was subsequently built at Porte Dauphine. Good luck to those who can find it today: Five anodyne blocks of concrete with the bronze medallion turned-green of Jean-Pierre in profile with his soft racing headgear. His life dates are beneath with no further explanation. There’s also the usual graffiti which curses everything today. It sits forlornly on the north side of the “rond-point” of Porte Dauphine, visible to anyone who happens to glance in the right direction from the ramp to “Le Peripherique.”

The metropolis of Paris, starting with the incessant din from the nearby ring road to the stately façade of apartment buildings on Boulevard Lannes, is very close by, encroaching in a palpable, physical sense. Once inside the park, joggers, bikers, and in-line skaters are still out in force daily for their dose of oxygen and exercise along the leafy alleyways. Then with the approach of nightfall, the fauna of the woods begins its ritual transformation, and the jocks and the mums head for home.

Left, Robert Bresson’s movie about a prostitute in the Bois de Boulogne was made in 1945.

Left, Robert Bresson’s movie about a prostitute in the Bois de Boulogne was made in 1945.

The cars now entering the Bois proceed at a snail’s pace that is unacceptable anywhere else in Paris. Headlights flicker before the beams catch signs of the first quarry of the evening: long legs in a garter belt and fishnet stockings backed against the bushes. A bit further are more fleeting figures, but in greater density and nudity. The silhouettes at one time used to only leer and beckon from the shadows but today, their audacity defies description in a non-adult magazine publication.

After so many years (and we choose our words carefully here), the red-light action in the Bois after dark has become just another titillating fixture of the Paris night scene. There’s no roar of engines anymore, just “odd” muffled sounds and the occasional car door slamming after dusk along some of the same pathways where over seventy years ago, a couple hundred thousand passionate French citizens had stood proudly, the spirit of their nation reborn. On September 9, 1945, they had wildly cheered-on as their heroes, men like Jean-Pierre Wimille and Raymond Sommer, tore about the woods in multi-colored machines, all-the-while helping put their country back on the road to recovery from war.

Next: The first Postwar Race

Thank you Peter for publishing this important piece of history by M. Berryman.

Pete–

…Just the sort of esoteric material we have come to

enjoy and expect from “veloce today”.

Had there been a European(World) champion then, then

J-P Wimille would have been the obvious choice with

his skill and maturity. Alfa Romeo so powerful until the

new dark horse Ferrari came along.

Jim Sitz

G.P. Oregon

Thank you for writing this amazing obscure part of my history. I learned how to drive in Paris in my twenties and I’m very familiar with those roads. I’m chuckling because I not only know them well, but we used to race with my friends there. Although I lived there at the time of the Peripherique, I remember pushing my then little Corsa to very unstable speeds…

Thanks for such a spot on article!