By Wallace Wyss

In 1959 Carroll Shelby won the biggest race there was in sports car racing, and that was the 24 Hours of Le Mans. He quit driving shortly after that, and just in time, because a heart condition he had managed to hide from the SCCA medical techs was threatening to take him out if he didn’t quit. He wasn’t worried about what he would do next; he was already was working on a plan to build his own sports car.

Although he was known for winning most of his victories in Ferraris and Maseratis, if you search deep down in the racing records you find that, among the fifty different marques of cars he drove was a Buick-powered special called “Ol’ Yaller”.

Shelby knew that the biggest expense in developing a new car was designing and engineering the chassis, the engine and transmission. If he could find a ready-made chassis that already had an existing engine and transmission, well then the problem was considerably smaller– only clothing it in an appropriately Italian sexy style and promoting it. He had spent too much time in Italy not to know that there were great designers and coachbuilders there. He also knew there was a snob appeal to having a car bodied in Italy. He probably had it in for Enzo Ferrari [according to historian Willem Oosthoek, when Shelby boasted of all his victories in the U.S., an unimpressed Enzo asked him: “But what was your competition?” Ed.]

so he thought why not stick it to the old man by having Ferrari’s own body builder build it?

His first idea was to use the All American Corvette. Hence the Corvette Italia.

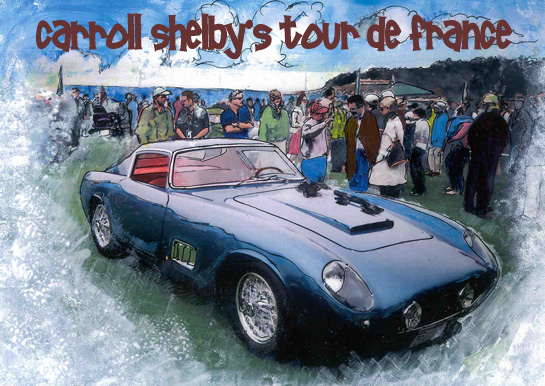

It wasn’t formally named that, it’s just the Corvette from Italy. Some others call it the Corvette Scaglietti, (pronounced SCAL-YETTI). At the time Shelby got the idea circa 1958-59, Scaglietti was Ferrari’s in-house coachbuilder, building the Ferrari 250GT in the TdF (Tour de France) body style. So it’s natural that the Corvette got much of the same lines. It could also be called Shelby’s Tdf, like our title.

SMUGGLED OFF THE LINE

Shelby planned to borrow the necessary chassis from his buddy at GM, Ed Cole, a real gearhead engineer who is largely credited with engineering the small block Chevy V8 and the Corvair. Cole figured he’d just divert a few chassis from the St. Louis Corvette assembly line.

Since Shelby, even after winning the 24 of Le Mans, didn’t have two nickels to rub together. He had to find investors, and did so, one being Gary Laughlin, a Texas oil man who had been running Ferraris and was miffed at blowing engines and gearboxes. [in fact the Corvette Italia idea may have originated with Laughlin..Ed.]

A guy by the of name Jim Hall was also involved. Hall, also a tall Texan like Shelby, is as quiet as Shelby is loquacious. Hall was a graduate engineer of Cal Polytech at this time and, while going to school in California took race driving lessons from, you guessed it, Carroll Shelby (who later ran a high performance driving school). Hall’s brother, Dick, was also partnered with Shelby in a business called “Carroll Shelby Sports Cars Incorporated,” importing various British cars from Lister race cars to Rolls Royces. Hall and his brother had inherited an oil business when their parents were killed in a plane crash. They dutifully kept the oil business going but got into the sports car business as well.

BOX STOCK

The specifications of the three Corvette Italias built were straightforward—box stock, right out of the Chevy catalog with no special suspension or engine tuning. Two of the three had automatics and one a four-speed manual. The chassis was a standard 1959 Corvette, including the entire braking and suspension systems, and if they had made a lot of them, they could have been serviced at any Chevrolet dealer. At least one of the three had Rochester fuel injection system mounted on its 283-cubic-inch V8 which would have given it a 315 horsepower rating. The gearbox on the one car with a manual was a 4-speed Borg-Warner T-10 with an aftermarket Hurst shifter and linkage.

The clue that this does not house a Ferrari engine is how wide the hood scoop is. Vertical front bumpers seem more like American ‘nerf bars’. Photo Wyss.

The bodywork was made in Italy by the then-common method of first making a full size “body buck” of wooden formers, and then having some apprentices hand-hammer sheets of aluminum into the separate shapes for the fender, hood, trunk lids, etc. , constantly comparing them to see if they fit the body buck.

The project died a-bornin’ as they say, although three cars were completed. Partly because it took two long years to build the three cars, a pace which would have never been enough to keep a car company going. And partly because Sergio Scaglietti was feeling the heat from his chief patron, Enzo Ferrari, who had thought of Scaglietti as his private coachbuilder, a relationship that would soon be formalized.

Born in 1920 Sergio Scaglietti began his career in the automotive industry at age 13. His father had suddenly passed away, with a little lying about his age, Sergio was employed at the same coachbuilder that had employed his father. (read Lynch on Scaglietti)

But he was ambitious like Shelby. At the age of 17 he joined a company formed by his older brother and a partner to build their own bodywork. They handily located the shop in downtown Modena smack dab across the street from a Alfa Romeo’s racing arm called Scuderia Ferrari, and in short order were repairing wrecked race cars.

Following WWII, Ferrari continued to bring the Scagliettis smashed cars to repair. Ferrari didn’t think of Sergio back then as someone who could create a body from scratch. That changed in the early 1950s when a man from Bologna brought in a damaged Ferrari barchetta with a body by Superleggera Touring. Ferrari happened to see the repair job and thought maybe these guys could build new bodies from scratch and began delivering new chassis to Scaglietti.

A major difference from the other coachbuilders like Ferrari was employing—Touring, Farina, Bertone, Zagato, was that the Scaglietti factory was not set up for mass production or even series production. Each car was still designed by the “eye” of the master so there are big differences from side to side and even from car to car even though they are in the same model series.

Among the most remembered Scaglietti-styled and built bodywork on Ferraris is the 500 Mondial and 500 TR and TRC, the classic pontoon-fendered 250 Testa Rossas, the 290 MM, 315 and 335 S, and, above all, the immortal 250 GTO, though in the last case the car was first cobbled together with body filler atop another body (nicknamed “the ant-eater”) and then delivered to Scaglietti with orders to re-do it in aluminum.

By the late 1950s, with Enzo Ferrari sweet talking a banker into giving him a loan so he could expand, Scaglietti was building coachwork almost exclusively coachwork for Ferrari.

When Ferrari sold out to Fiat in 1969, Scaglietti saw a chance to cash out and become an employee again. He hadn’t enjoyed the later years as much, when labor strife was common in Italy. Though he sold his firm along with Ferrari, he continued to run the custom coachbuilding shop at Ferrari until his retirement in the mid-‘80s.

Interior looked Ferrari except for American sourced gauges which no doubt worked better anyway Side vents similar to those on the TDF. Photo Wyss

THE BRASS INTRUDES

What also stopped further Shelby Italias from being built was the big brass at GM who made it abundantly clear to Ed Cole that the firm had decided to go along with the Automobile Manufacturer Association’s ban on a tie-in with racing. You had to be there to understand it, but basically car racing then was thought of as some reckless hillbilly thing—go like hell and devil take the hindmost. American teenagers were being killed right and left and there was a safety crusade where the do-gooders thought banning automakers tying in with race promoters would make cars safer, when in fact it was the equipment that came out of racing–like seat belts and disc brakes–that eventually made cars safer.

There were also practical considerations. In Detroit, there was something called a “line speed,” and that referred to how fast cars came down the line. Corvettes had a slower line speed than most anything Chevrolet built but you can imagine the chagrin of the plant manager when those three regular Corvette bodies appeared from Molded Fiberglas Co. in Ashtabula, Ohio and they were three chassis short! Ed Cole got his ear roasted off by the brass.

At Corvette, Zora Arkus-Duntov was taking great pleasure in skewering Shelby’s plan. Duntov, who had raced a Porsche at LeMans in ’53, and was GM’s most knowledgeable man in terms of endurance racing, also saw Shelby as a rival. He knew it was “give him an inch, and he’d take a mile” so the best idea was to head Shelby off at the pass. Only four years later Duntov had his own race car project going, the ill-fated Corvette Grand Sport, also killed off by management.

Well, what to do now. Shelby was seen moping around, waiting for a shot, and good luck was just around the corner. Around 1961, he had lunch with John Christy, an editor at “Sports Car Graphic”, who happened to mention that A.C. Cars Ltd., makers of the beautiful A.C.-Bristol sports car, would be ceasing production of their car because the engine supplier, Bristol, would no longer be making the BMW-based six cylinder engine available. Shelby coupled this information together with the fact that, while visiting the Pike’s Peak hillclimb a buddy, Dave Evans, a Ford engineer, had spilled the beans on an upcoming Ford project– a little 221 cu. in. V8 that was cast iron but still lightweight and since it was a truck engine, damn durable. (By the time sample engines got to Shelby it was already upsized to 260 cu. In.—Ed.) Shelby, by about his third martini, decided when he got back to the office, the first thing he’d do was call A.C. and tell them that he had an engine for the “Ace” and then he’d call Ford and tell them he had a sports car to wrap around that engine.

He knew that a fellow named Lee Iacocca at Ford was a young up and comer, who had let it be known he was interested in developing a Ford that could humble a Corvette. The Thunderbird had been raced, but found wanting. It was too heavy, too clumsy, and had the wrong engine.

So it was that the idea of the A.C. Cobra was born.

What about the pizzazz of being able to put a badge on it that said made-in–Italy? Shelby figured that although it was nice thing to be able to say about a car but, seeing as how the Italians were so slow at making a car, that made-in-Italy label didn’t do him much good anyway.

From that point on, Shelby went British, and the Corvette Italia was reduced to the status of a footnote in history.

Wallace Wyss is the author of SHELBY: The Man. The Cars. The Legend. It can be ordered from straight from the publisher, Iconografix , on their toll free order line (800) 289-3504

Fascinating article. Thanks for this glimpse into the older stepbrother of the Cobra. And I love the art!

Congrats to Wally Wyss for the fascinating story and artwork accompanying it!

Please bring more of his stuff…