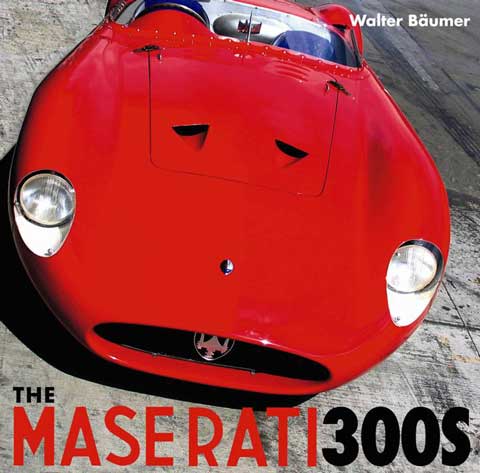

Maserati 300S by Walter Baumer

Review by Pete Vack, Editor, VeloceToday

295 mm x 290mm, 360 pages, 390 historical black and white and color, case bound with dust jacket and slip case. Price, $155 USD

The most dog eared books (the ones most referred to and therefore cherished) we have in our office library are those with the little numbers and big pictures (both literally and figuratively).

We have just received the second edition of Simon Moore’s Immortal Alfa Romeo 2.9, and already have his even more magnificent Legendary 2.3. A long time favorite is Marcel Massini’s Ferrari by Vignale, in need of an updated second edition but still as close to hand as a GTO gear lever. Speaking of GTOs, Bluemel and Pourret’s Ferrari GTO is indispensable, and poor Luigi Fusi’s All Alfa Romeos Since 1910 is almost falling apart from use. We couldn’t go to sleep without knowing that the Orsini/Zagari OSCA book is safe at hand. Willem Oosthoek has given us the individual histories of the great Maserati 450S, another favorite with a short shelf life. There are many others but you get the drift.

And now comes Walter Baumer, a historian and consultant for classic Maseratis with a will, passion and ability to hunt down the twenty eight known Maserati 300S sport racers. Baumer has done a compelling, interesting job and assembled a great number of previously unpublished photos; his book is also the first to present the complete history of the 300S. In the opinion of many, the 300S itself was best all around sport racing car of the 1950s, Ferrari be damned. A veritable 250F with mudguards, the 300S was the favorite of Moss, Fangio, Behra, and many other lesser lights. The combination of the two, Baumer and the 300S, while not quite magic, is most certainly worth the paltry $155 charged by Dalton Watson for the pleasure of adding this to your shelf. It will be, and in fact already is, one of our favorite dog eared books.

As should be expected in such a work, included in each of the chapters, approximately one per serial number, are the list of known races in which the car participated, a rundown of each significant event, identifying features and most owners to the present day.

The Maserati 300S goes the extra mile, including in the text interesting and informational chapters. Baumer provides a full technical description, a breakdown of the physical changes of the cars, a full chapter on numbers and numbering system for the chassis, engine and internal serial numbers, and illustrates the sales and ads featuring the 300S. He provides a competition background, discussing the racing activities in Europe, Italy and the U.S. He lists the surprising number of Mystery Cars, discusses the rare 350S, and provides copies of the 300S owner’s manual. Finally, Baumer provides a chapter about the personalities associated with the era of the 300S and includes figures such as Mimmo Dei, the man behind the famous Centro Sud racing team.

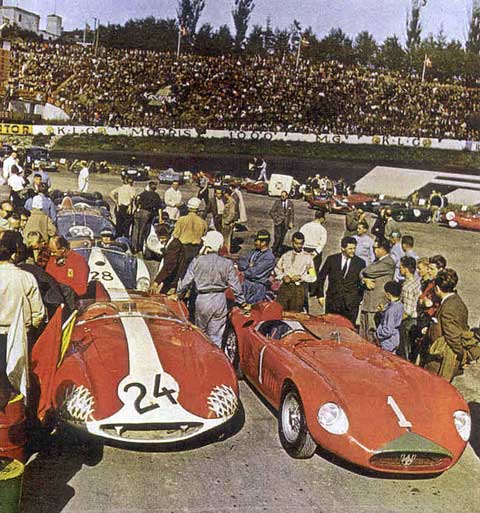

We must also mention that the 390 historical photographs are large, fresh, and thoroughly enjoyable. If there is any complaint here it is that some of the original photos were enlarged perhaps too large and lose some focus and quality. This is offset by the stunning original color photos that are liberally sprinkled through the book. From these, it is easy to see the shade of red most often used by factory cars–definitely and orange/red, far from the local fire truck red often used even today. Baumer has made good use of his relationship with the Cahier family—just thumbing through the book one notices the really excellent photographs are inevitably by the late Bernard Cahier. Good photos need good paper–in this case 170gsm Stora Enso Matt Art, 295 by 290 mm in size. That’s an excellent, semi gloss heavy paper which allows the historical photos to be to presented in the best light.

Moss driving the battered 300S owned by Bill Lloyd to victory in the Bahamas in 1956. Courtesy Walter Baumer.

The Maserati 300S was a favorite choice of the cognoscenti; Briggs Cunningham ordered the first three built; chassis 3051, 3052 and 3053. The new Maserati immediately made its mark. 3051, raced and possibly actually owned by Bill Lloyd, entered its first race at Thompson, in Connecticut, on May 1, 1955, winning the first time out. Lloyd campaigned the car throughout the 1955 and 1956 SCCA season, with good results. At the end of 1956, he entered 3051 at the Bahamas Speed Weeks, bashed the nose in one race and handed the battered Maserati over to Stirling Moss for the feature, which Moss won.

Privateer and Maserati customer Franco Bordini presents the quintessential image of the 1950s Italian race driver. Courtesy Walter Baumer.

As Baumer finds, a number of the 300S cars were built specifically for the factory team, but were often lent to privateers at times for a variety of reasons, most of which having to do with money, which was always short.

Chassis 3055 was a factory car, in which Jean Behra took to a win at Bari, Italy, in May of 1955; Perdisa and Mieres took third with the car at Monza and Musso and Valenzano used the car at LeMans in June but DNF’d. Then, privateer and good customer Franco Bordini borrowed 3055 for a hill climb and took first place. By November the car was back with the factory and Luigi Musso drove it at Caracas but again did not finish. Needless to say, the very Italianate life of a racing Maserati made Baumer’s job tracking each car somewhat miserable.

Rarely seen mistakes of the master. Fangio looks over the damage he has wrought on Godia-Sales 300S. Courtesy Walter Baumer.

The life of chassis 3066 followed a similar pattern, a factory works chassis delivered to Francisco Godia-Sales, a good, solid amateur driver who also owned and raced a 250F. The new owner raced the car throughout the 1956 season on his own, but at Sweden in August, 3066 was appropriated for the team and Godia-Sales co-drove with Joakim Bonnier. In January of 1958, the Godia-Sales 300S made an appearance at the 1000Km of Buenos Aires, and in the hands of Juan Fangio it suffered moderate damage–a result of one of Fangio’s rare mistakes. Godia-Sales was reputed to have remarked that’to crash the car, I wouldn’t have needed Fangio!’

On of the many of the era color shots in the 300S book—note the orange/red color of the Maserati paint. Courtesy Walter Baumer.

Another problem chassis detectives must solve is the confusion resulting as a result of a chassis being re-numbered by the factory and then resold. Chassis 3080 was a bit of a mystery at the beginning, but Baumer tracked it down to a car used by Stirling Moss at Oporto in 1958, and borrowed again by Moss for a series of races held in Sweden and Copenhagen later that year. At that point, 3080 was returned to Modena, apparently renumbered as 3083, and sold to the U.S. Maserati dealer in Long Island. In 1971 the same car appeared in an ad which claimed it had only 2000 miles and had never been raced.

The most tantalizing part of the book deals with the dozen mystery cars that appeared in races but lack a positive id. Many may still be lying in a shed, (probably in South America, where a large percentage found a home late in life). Baumer lays out the evidence, tries to put the pieces of the puzzle together, and hopes that in publishing the book, some of the mysteries will be solved.

While happily tromping through the many pages of Baumer’s book, we noted a few niggling errors but none serious enough to make light of. Maserati historians, known at times to be pretty critical, will probably find something objectionable between the covers, but that is how things are learned and facts corrected. Baumer’s book is not the last word on the subject, but it will be some years before another attempt is made to chronicle the history of the 300S.

With Christmas just around the corner, make sure you put this book on your list of things you can’t live without.