The OSCA 750 of Gordon/Bentley when owned by Oliver Collins. Credit Lucine Collins

In 1960, shortly after the team of John Bentley and Jack Gordon won the Index of Performance at Sebring, Karl Ludvigsen asked them if he could drive the car for an article in “Sports Cars Illustrated.” The report was published in the August 1960 issue. Karl has given VeloceToday express permission to republish that article. Also, read Jack Gordon’s account of the race.

By Karl Ludvigsen

One of the most consistently successful makes of cars in racing over the past decade has been one of the smallest machines from one of the smallest factories: the OSCA.

The cars from Bologna only occasionally put in brilliant performances and have often been defeated by more modern sophisticated sports-racing cars, but in the background there’s a steady, impressive record of wins and high placings notched up primarily by private owners. Within this framework, one of the most consistently competitive OSCAs has been the superb little 750, whose most recent major win has been reviewed by John Bentley on the preceding pages.

“I used to kid people about that big box with 5000 rivets in it, told them it was the steam boiler that made the car go.” Jack Gordon.

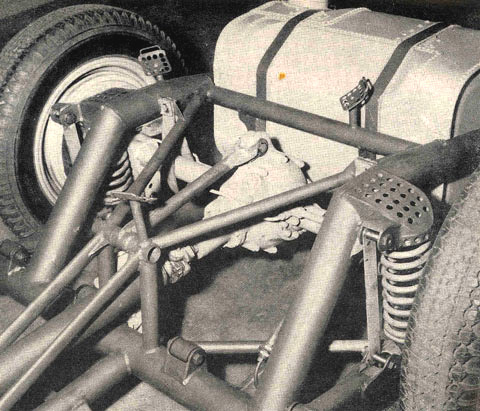

When the Maserati brothers first visualized a 750cc car, to be ready for the 1956 season, they saw it as having a space frame of small-diameter tubing, with a rectangular-sectioned U-shaped front cross member on which the front suspension was to be mounted. This idea was dropped in favor of the perennial OSCA two-tube ladder frame, with one important break from the past. All previous OSCAs had, first, plain semi-elliptic rear suspension and, later, a trailing quarter-elliptic plus radius-rod layout much like that now used in the Healey Sprite. The 750 was the first to use the coil-sprung triple trailing arm system that’s now employed on all OSCAs.

Square to Oversquare

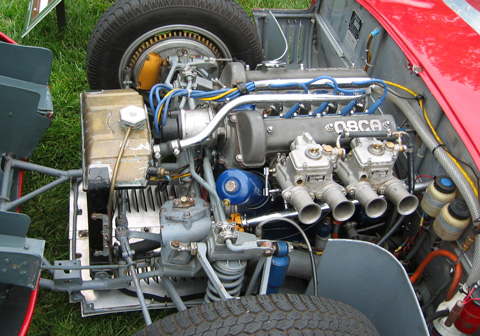

Designated the S187, the original 750 cc OSCA engine was and is a beautiful little piece of work, characteristically over-designed, like the rest of the car, to guarantee reliability and maintenance ease.

This is the OSCA 750cc engine, three quarters of a liter, 45 cubic inches, smaller than anything on the U.S. market today. The Smart fortwo has a 1000 cc engine.

This is the OSCA 750cc engine, three quarters of a liter, 45 cubic inches, smaller than anything on the U.S. market today. The Smart fortwo has a 1000 cc engine.

Photo credit Lucine Collins

From 1956 until recently, its dimensions had been unchanged (62 x 62mm), as has been its power output (70 bhp at 7500 rpm). Perhaps in response to the pressure that’s being applied by Mr. Abarth’s very quick twin-cam Fiats, the Maserati brothers have finally given the 750 a complete top-to-bottom redesign, ending up with the car we show here: the type S187N. By OSCA standards this is revolutionary change, though the difference is far from obvious to a casual glance.

If you are enjoying this article, why not consider a donation to VeloceToday? Click here for details

Most fundamental are new dimensions of 64 x 58mm, producing a displacement of 745.9 cc against 748.7 before. Up at the top the cylinder head has been completely revised, the most obvious change being the relocation of the carbs on the left and the exhaust pipe on the right. This had been done a couple of years ago on the 1500s for the first time, and seems to be beneficial to the exhaust layout and carb linkages. Also, the V inclined valves are placed at smaller angles to the vertical than they were before, a change which makes it possible to slant the intake ports up a bit more to gain a straighter run for the incoming mixture. In turn this slant has been made practical by a new design of Weber carburetor designated 33DS, which has the customary twin throats cast at an angle to the central float chamber. These very nice new carbs also have a revised top lid with a single circular cover that can be removed to get at all the most-used jet and float components.

Another change has been in the location of the pivots for the finger-type cam followers, which are now all placed in the central vee, possibly to give maximum room for ports along the sides of the head. As might be expected, the timing is generous:

Intake / Exhaust

Opens 48 degrees BTDC / 75 degrees BBDC

Closes 66 degrees ABCD / 31 degrees ATDC

Duration 294 degrees

Overlap 79 degrees

With compression ratio at 9.5 to 1, the S187 N engine delivers 75 bhp at 7700 rpm, and develops its peak torque of 58.6 lb-ft at a very high 6000 rpm. Here are the factory recommendations on rev limits:

7200 through the gears is absolutely safe. Maximum to be sustained for any length of time is 7400 to 7500, while the maximum for short periods is 6600 to 7800. Winding through the gears at Sebring, the Bentley/Gordon team saw 8000 frequently with absolutely no difficulty.

Behind the Wheel

This was obviously an automobile worth getting better acquainted with, so arrangements were made with George Weaver to take the Sebring-Index winning car to the new Thompson track for some fast lappery. Thompson was perfect for the OSCA since it’s a twisty course that puts a premium on precise handing, but unfortunately it offers no level straights that would allow performance checks to be made.

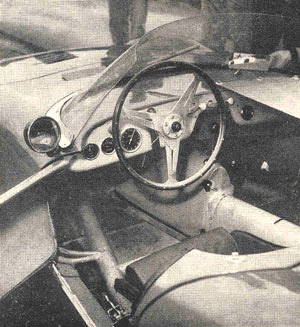

Since it has a low, simple frame, the 750 can have a genuine door that makes it fairly easy to clamber in and out, while keeping an eye open for easily-bent paneling. Placed very low, the bucket seat is a snug, comfortable fit and offers good lateral support. Thanks to the change made by the customer in the steering-column height, there’s adequate thigh space, but the leg room is not exceptionally generous and the pedals are placed high in relation to the very low seat. With the high windshield up close and the half-tonneau cover buttoned in place, it’s cozy.

Cockpit is classic, note gearshift lever.

The “office” is laid out strictly for business, with a small diameter tach at the left, next to the dials for oil pressure and water temperature. There’s a big cut-out at the center for the stubby, round-knobbed shift lever which is placed well forward, calling for a short reach. Reverse is guarded by a pull-type lockout latch. To fire up the mechanism, you press hard on the stiff, short-travel clutch and tug on the starting lever to the right of the shift tower.

Clutch In and Away

To get rolling, the usual non-racing start is made: quickly pop the clutch in at low revs, just a bit above idle, then apply judicious throttle just before the engine stalls. This method is the easiest on drive lines, and is a snap with this OSCA’s remarkable engine. Belting off down the track, I found that from 2000 rpm on up the 750 pulls cleanly and steadily. At 4000 is starts to deliver useful power (you wouldn’t want to get below that point when racing it), and at 6000 and above it comes to life and runs rapidly away, piling up rev upon rev with furious haste–accompanied by a striving rasp from the exhaust. The sound isn’t annoying, since it’s away on the right under the car, but crisp, clear and reassuring.

Recently, SCI has been trying some Fiat-powered Formula Junior cars that offer power peaks much like that of the 750, but the feel is entirely different. In a highly tuned pushrod Junior you can reach and exceed 6000 rpm but the engine usually feels a hair nervous doing it, with all that monkey motion thrashing around. In contrast, the thoroughbred twin-cam OSCA feels hard, solid and free no matter how high you spin it, actually biting in and performing best when it passes 6000. And remember that our OSCA impressions were gained after the car had traveled for twelve hours at Sebring, with no subsequent attention at all. The initial investment for a car like this is high, but he upkeep should be minimal.

Learning the Gears

There is effective synchromesh on third and fourth gears, where most cog-swapping is usually done on faster tracks, but the non-synchro second gear takes a bit of learning. Both when coming up from first and going down from third it can be elusive, especially in the latter case when the rather wide shift pattern slows down your approach. But the key to mastery lies in a positive “you’re going in or else” attitude, which the husky-feeling gears seem well able to withstand. Actually, after only the shortest acquaintance second gear starts snicking right in, and the rest is easy. With its 5.00 to 1 rear-axle ratio, this car was geared just right for both Sebring and for short courses like Thompson.

Huge in size for such a small car (it weighs 948 pounds dry) and newly transverse-finned, the brakes are more than up to all demands. Pedal pressure required is lower than on many competition cars, with the new front linings that were fitted just before our trial. Twin fluid reservoirs feed a new Lockheed master cylinder, which incorporates separate circuits for the front and rear braking systems.

Excellent Handling

Happy Karl.

Now for the best part; taking the OSCA through Thompson’s challenging corners. Conditions weren’t perfect, with a damp track and Firestone tires with a relatively hard tread compound, but they were good enough for SCI to classify the OSCA as one of the finest-handling cars it has ever tried. First, the steering is quick with a very good lock (turning diameter : 33 feet). It has that elusive just-right ratio that provides fingertip lightness without ever making it necessary to remove your hands from the rim for the tightest corners, and transmits a steady, reliable indication of the prevailing “bite” at the front end. The steer characteristic is perfectly neutral, or as near as makes no difference, which means that the car goes where you point it and is absolutely viceless. The throttle pedal can usually be called on to swing the tail into position, depending on how fast you’re going and what gear you’re in. Does it lean? It may, perhaps on drier surfaces, but I never detected it. Adding all together, this is the most predictable, controllable and utterly sweet-handling car you can possibly imagine, and as Chevy says, it’s better than that!

The most lasting impression the 750 OSCA gives is of complete solidity and durability. The Maserati brothers obviously build them to stand up to the rigors of the classic races like the late Mille Miglia and the Targa Florio, leaving a generous safety margin when the cars are used in short club events on smooth tracks. British builders have made lighter cars by paring this margin to suit the track, which is why you never hear of a Lotus or Elva, say, doing anything in the Targa. Its careful, correct breeding from a classic layout gives the OSCA an harmonious feel, a vigorous, competent air. It is without question the finest automobile of its class, and is among the greatest sports cars of the world.

0.75 litre is indeed smaller than a smart but the performances are a world apart.

the osca had full road equipment, head & tail lights, license plate light, horn, windshield wiper (no turn blinkers, you use hand signals).

in the 1960’s when living in rockaway new jersey adjacent to interstate 80 i used to occasionally borrow a dealer plate from kas krag’s store where i was working part time & go out at night & cruise the superslab when traffic was light. molto funissimo.

> jack

I had a freind who raced a 750cc OSCA engine in what I was told was a Maseratti chassis. His name was Jim Scott and he owned VW dealership in McHenry Ill. The owner of the car was Ollie Schmidt. He virtually eliminated the chances of those of us who were racing Crosley powered cars in H-Modified, but I didn’t care since the car was the sexiest one I had ever seen.