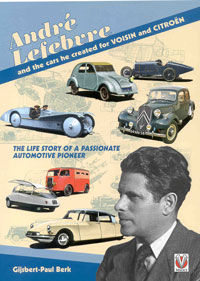

André Lefebvre and the cars he created for Voisin and Citroën

by Gijsbert-Paul-Berk

Veloce Publishing, 2010

$39.95 USD

Order here

I admit to being heretofore unaware of the importance of André Lefebvre. There are two reasons I knew so little about this brilliant and accomplished French engineer. According to his biographer, Gijsbert-Paul-Berk, the first is that engineers, particularly in France, work more or less “incognito”. The second is that in 1958, Lefebvre suffered a stroke which prevented him from writing his memoirs. Lefebvre however, was also not one for self promotion. We might add a third. Few people in America today are cognizant of any type of French car. Should we expect much ado for the mere engineer?

Of course not, and that’s why VeloceToday does what it does, and why we are thankful for Paul-Berk to have gone to considerable lengths to bring us Lefebvre’s very interesting story.

For André Lefebvre was in large part responsible for the Traction Avant, the H series Citroën trucks and vans, the 2CV and the DS. (Paul-Berk refrains from hero-worship and gives plenty of credit and text to the many engineers and managers who were as instrumental as Lefebvre.) To have been responsible for just one of these cars would have been worthy of a nomination to the Engineering Hall of Fame. And as Paul-Berk discovered, Levebvre had a good bit to do with Voisin as well.

Let’s dispense with the criticisms of the book before we go further. It is a slim volume, 10 x 7 inches with only 144 pages and very well illustrated throughout. The font, refreshingly large, is accompanied by a similar but Italicized font for the long captions, and often the text and captions seem to run together as one tries to find out what happened to the rest of the sentence. This is a layout problem, not one of the author. A few subjects did not need to constitute an entire chapter…chapter five, for example, is one page describing the effects of the Depression in France. The book is not footnoted, though references are usually clear and in the text. It does have a small index, with appendixes that include a bibliography. None of this greatly detracts from the whole, but there you have it.

Attempting to write a biography of someone who departed our world in 1964 and left few diaries or personal notes, was not included in many contemporary articles andwhose peers are also long gone, is not an easy task. But as the author points out, two books, long out of print and never translated into English, were essential for the biographer. The first was Roger Bioult’s two volume history “Citroën, l’histoire et les secrets de son Bureau d’Etudes” which provided much needed anecdotes and insights. Lefebvre’s first employer, Voisin, considered him his ‘spiritual son’ and had several references to Lefebvre in his autobiography, “Mes mille et une voitures”. In addition, Lefebvre’s sons (and daughter-in-law) all contributed stories, anecdotes, recollections and most of all the many personal photographs which serve this book so very well. Therefore Paul-Berk rarely resorts to speculation for fill in, though it does occur at times.

Lefebvre was born in 1894 to a father who ran a successful corset factory (corsets were expensive, but ultra fashionable) and a mother who was a paramedic. The family enjoyed an upper middle class environment. Young André was interested in math and mechanics, particularly if associated with those new flying machines. At 17, he entered the Ecole Supérieure de l’Aeronautique et de Construction Mécanique, or “Supaéro”, a new college which trained aeronautic engineers. In 1914, WWI broke out and Lefebvre was ruled out of the military service due to rheumatic fever and was further saved by getting a job in the new aero industry, hired by Gabriel Voisin (1880-1973) himself. Aside from a brief and unhappy period at Renault (he and the old man did not see eye to eye), Lefebvre would be employed by only Voisin, until 1930, and Citroën (1934 to 1958).

Throughout the 1920s, Lefebvre was both an engineer and responsible for the Voisin records cars. Lefebvre is in the light coat next to the driver. From the book.

All’s quiet on the western front until about 1919, when there’s a photo of the handsome young man himself next to the new C1 Voisin, driving it with his mentor from Paris to Cannes while setting some very impressive but unofficial times. Exactly what Lefebvre was responsible for at this period is not certain, but by 1922 he was definitely deeply involved in the creation of the Knight engined (and therefore out of serious contention) C6 Course, that ugly but efficient Tours Grand Prix race car. In fact, Lefebvre entered the race and placed fifth, the only C6 to finish. But it was a salient point in the young man’s career. From then on, his star was ascendant.

Early on, and including a time at Voisin, Lefebvre was interested in the latest lightweight materials and the use of front wheel drive. His belief in front wheel drive was so intense he argued to the point of dismissal with Louis Renault on the subject. Renault refused to consider it, “I won’t waste five minutes on such nonsense,” Renault reportedly said of front wheel drive. Lefebvre was out, and it would not be until the R-4 of 1961 that the firm employed front wheel drive. Fortunately, someone else was all ears for a new front wheel drive car and that was André Citroën.

There was nothing conventional about the Traction Avant. It embodied all of the bold ideas of both Citroen and Lefebvre. From the book.

Citroën already had a team in place, the idea, and the nerve to create a truly radical front wheel drive sedan. Lefebvre came along at the right time, with the right talents and was told to lead the engineering team to build a completely new car within an unheard of 13 months. It wasn’t easy, there were horrible teething problems, but in time, the Traction Avant prevailed and saved the company.

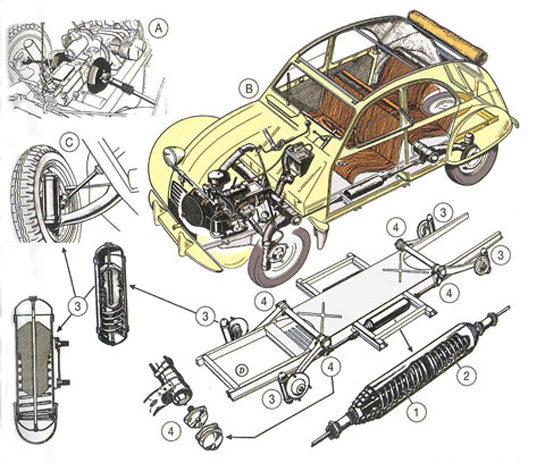

Two people are generally acknowledged to be the fathers of the 2CV—Pierre Boulanger and director of the Bureau d’Etudes Maurice Broglie. But again it was Lefebvre who was put in charge of the development of the Deux Chevaux particularly in the chassis department (he left Maurice Sainturat and Becchia alone with his unique hemi head two cylinder). The result was even a more successful car than the Traction Avant.

The 2CV, conceived by Boulanger and realized by Lefebvre and his team, was a masterpiece of original thinking. From the book.

By the early 1950s, while a total of 759, 123 TAs were being built, it was obvious that a new car was necessary. And what a new car it would be. The Citroën DS of 1955 was and remains one of the most advanced cars of the twentieth century, an absolute landmark in engineering and sheer inspiration and another effort headed by the still energetic Lefebvre.

Along the way, Paul-Berk provides dozens of diagrams, photos and images related to the development of every car discussed and gives full mechanical details. Get inside the design, and you will get inside the designer; we give full points to the author for both illustrations and explanations.

An interesting, somewhat tragic and ironic story: First, the man who hired Lefebvre, André Citroën died of a heart attack shortly after the TA was introduced. Michelin steps in, and Citroën is headed by Pierre Michelin, who got on well with Lefebvre, allowing him to fulfill the promise of the Traction Avant. In December of 1937, Michelin went off the road and was killed, driving a Traction Avant. Upon his death, Pierre Boulanger took the reigns of the company, created the concept of the 2CV, and began to plan the DS along with Lefebvre. But in November of 1950, Boulanger was killed in a road accident. He was driving a Traction Avant. The losses, both occurring with the Lefebvre-designed TA, hit the designer very hard. It was almost too much to imagine.

Always on the cutting edge, Lefebvre's last effort was the Coccinelle. This C10 was built in 1956. Photo by Simon Wright.

Nevertheless, even after the success of the DS, Lefebvre pursued the car that would eventually displace the now beloved 2CV. Called the “Coccinelle” (ladybug) project, the planned replacement was shaped like a teardrop, be ultra light, very aerodynamic, a four seater with plenty of room for luggage. “This concept was so advanced that I exceeded everything Lefebvre had created before,” wrote Paul-Berk. For the first time the famous artist and designer Flaminio Bertoni who had perfected the TA and DS, was not involved as it was too streamlined. Ten prototypes were said to have been built and the C10 remains. Lefebvre’s illness in 1958 put an effective end to the project. Perhaps all for the better. Times were changing, and the management at Citroën were no longer willing to take on the huge risks associated with such an advanced car as the Coccinelle. The 2CV was eventually replaced by the much more conventional Ami 6.

Rest in Peace, André Lefebvre.

Further reading

The 2CV: Improbable, Impertinent, Imponderable

Citroen Prototypes

Other books about Citroen available at our bookstore:

DS Buyer’s Guide

2CV Buyer’s Guide

Nice book with good price: I bought at once in July 2009

The first part, about Voisin, is almost complete, not the second one (Citroen) too poor of pictures and superficial analysis of the projects’s histories…[what a pity ]

]

>>