By Pete Vack

When I first discovered Thoroughbred & Classic Cars magazine in the mid-1970s, I was beyond thrilled. But until now, I knew very little about how it came about, so I asked an early contributing artist, Rodney Diggens, to give us his insights. He did so, then got in touch with TCC’s founder Lionel Burrell, who in turn emailed first editor Michael Bowler and features editor Jonathan Wood, and suddenly we had a great story! We hope you enjoy this as much as I enjoyed those early, breakthrough issues of this incredible magazine that changed our hobby.

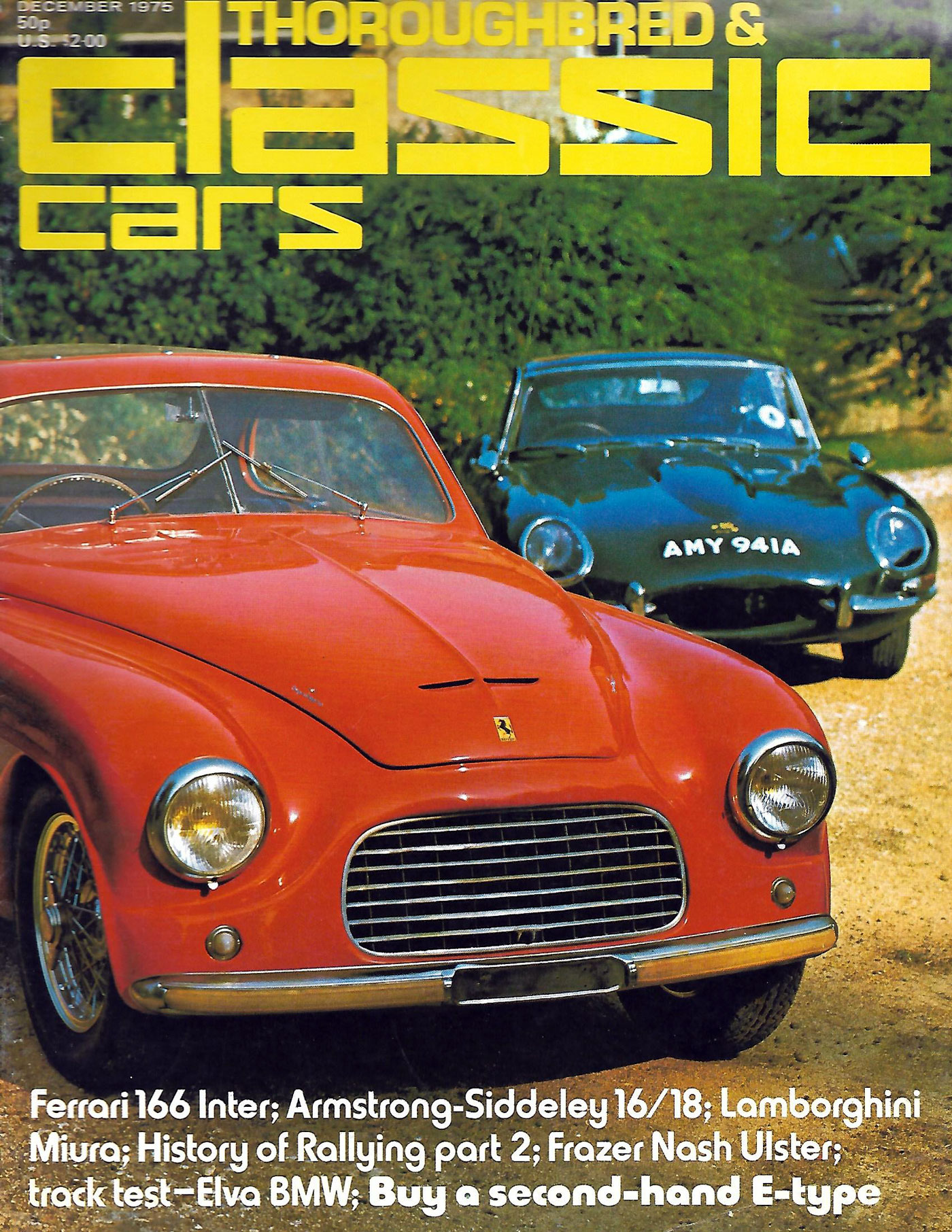

Today, with all the classic car media, it is hard to realize the significant impact TCC had on the hobby when it was first published in September, 1973. Here in the U.S., we had little to choose from as there were very few magazines devoted to classic cars. Notably The Bulb Horn, Antique Automobile and Horseless Carriage Gazette were around and are still, but for club members only. The Classic Car and Car Classics catered to the American car crowd, and only Special Interest Autos had much about post war European classics. Road & Track offered up a few historical articles and the Salon feature, but that was the extent of it. And there was Automobile Quarterly, great but only four times a year and very expensive and subscription only. TCC’s great rival, Classic and Sportscar, didn’t come along until 9 years later!

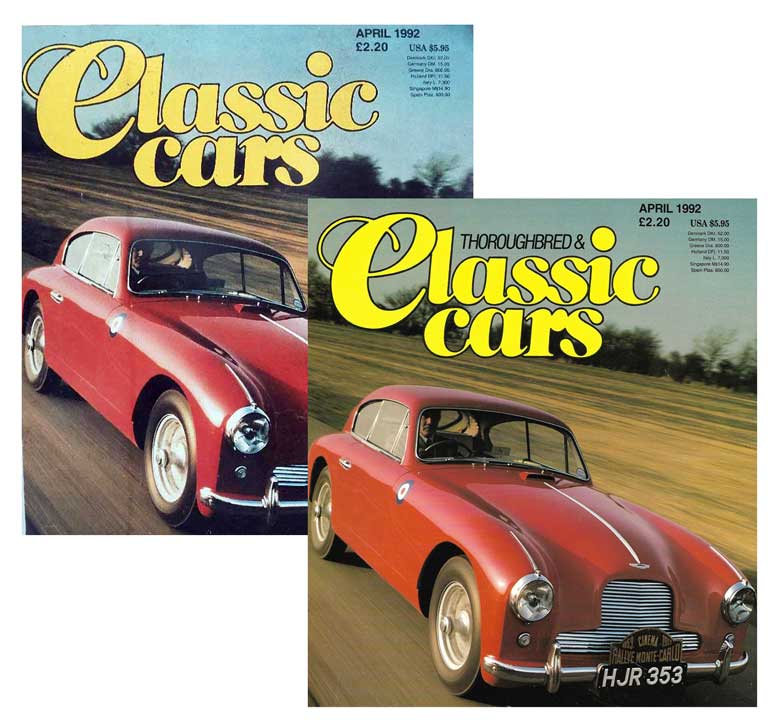

In the early 1970s the VSCCA in the US was growing rapidly, and Steve Earle was about to unleash the Monterey Historics, which would change the nature of, well, everything. TCC was at the right place at the right time, and what a joy it was to read. The magazine was launched as Classic Car magazine but to get a foothold in the U.S. market – again something no other foreign magazine sought out – it was named “Thoroughbred & Classic Cars” for use in the States as several U.S. interests objected to the short moniker.

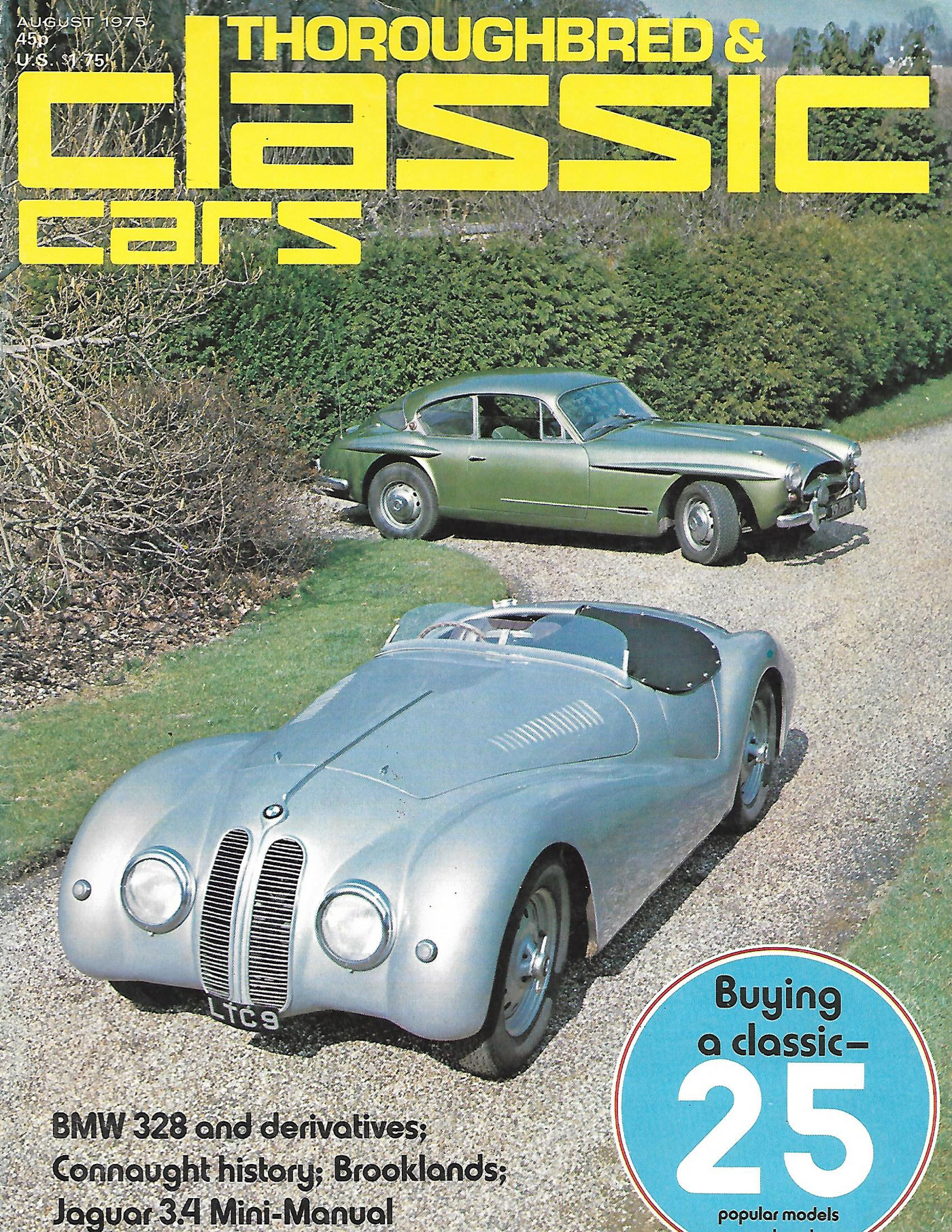

TCC really struck a chord not only in the U.K. but in the States. By the time I discovered the magazine and subscribed, I had missed more than the first year. But when it finally arrived it was a godsend. I received my first issue in August of 1975 and there on the cover was Michael Bowler’s BMW 328, and inside was packed with great columns, histories, ‘Our Cars’, classified ads, how to, models and you name it, everything possible for the classic car enthusiast. In addition, the contributors were the tops in their field: Paul Skilleter, Graham Robson and George Bishop and even Simon Moore! Below, founder Lionel Burrell, editor Michael Bowler, features editor Jonathan Wood, and contributing artist Rodney Diggens recall the birth of the magazine.

Lionel Burrell

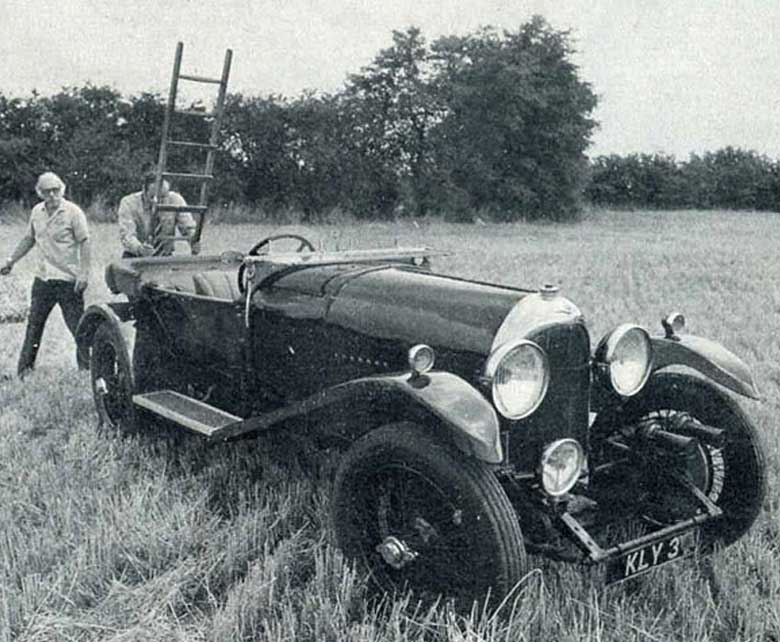

Writes Burrell, “One of my cars. It is because of my Bentley KLY3 and my job at Autocar that my idea for a new magazine called Classic Car came about in 1973.”

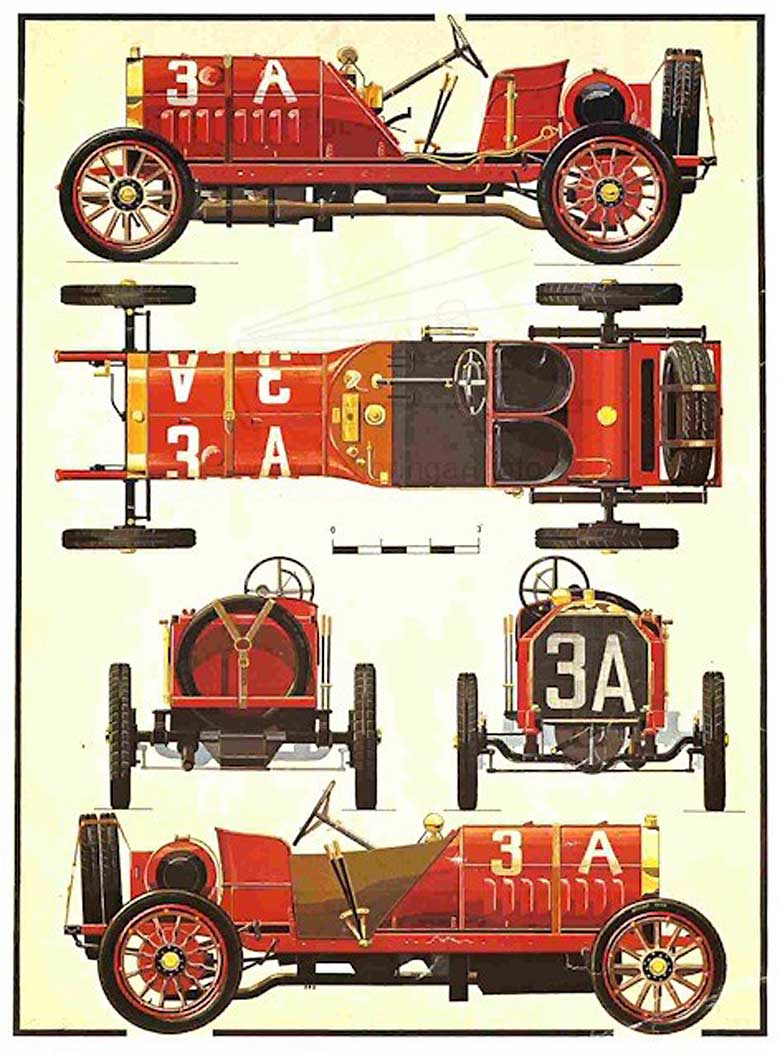

The man behind the magazine was Lionel Burrell, who after a spell as art editor of Autocar, was the originator of what was to become the world’s best-selling classic car magazine. Burrell was art trained in Manchester at the Junior Art School and then at the Regional College of Art. He joined IPC magazines in the late ‘50s before becoming Art Editor of Autocar magazine in 1968, and in 1973 launched Classic Car. His artwork was always somewhere in each issue, usually on the back page, such as this of the Fiat.

Burrell freelanced from 1960 to 1995 for Car magazine, Classic Car Profile publications, The Motor magazine, Eagle Comic and a number of national newspapers. He has owned over 40 vintage and classic cars and a 1946 Piper Cub Aeroplane and also helped start the world’s first classic restoration course at The Colchester Institute.

He has owned and restored Jaguars, Aston Martins, Triumphs and MGs, including an MGB. Has just sold his Bentley after 60 years and still has a 1955 and 1953 Sunbeam Alpine.

Burrell emailed a copy of his April 1992 edition of TCC. Note the lack of Thoroughbred & in the title, whereas the bottom cover is the U.S. version with ‘Thoroughbred &’ in smaller font. The cover shows another car which was restored by the Colchester Institute was a 1955 Aston Martin DB2/4. “After the car was finished had cost me, not the magazine, about £24,000. I had to sell it and it went to Germany.” wroet Burrell.

Michael Bowler

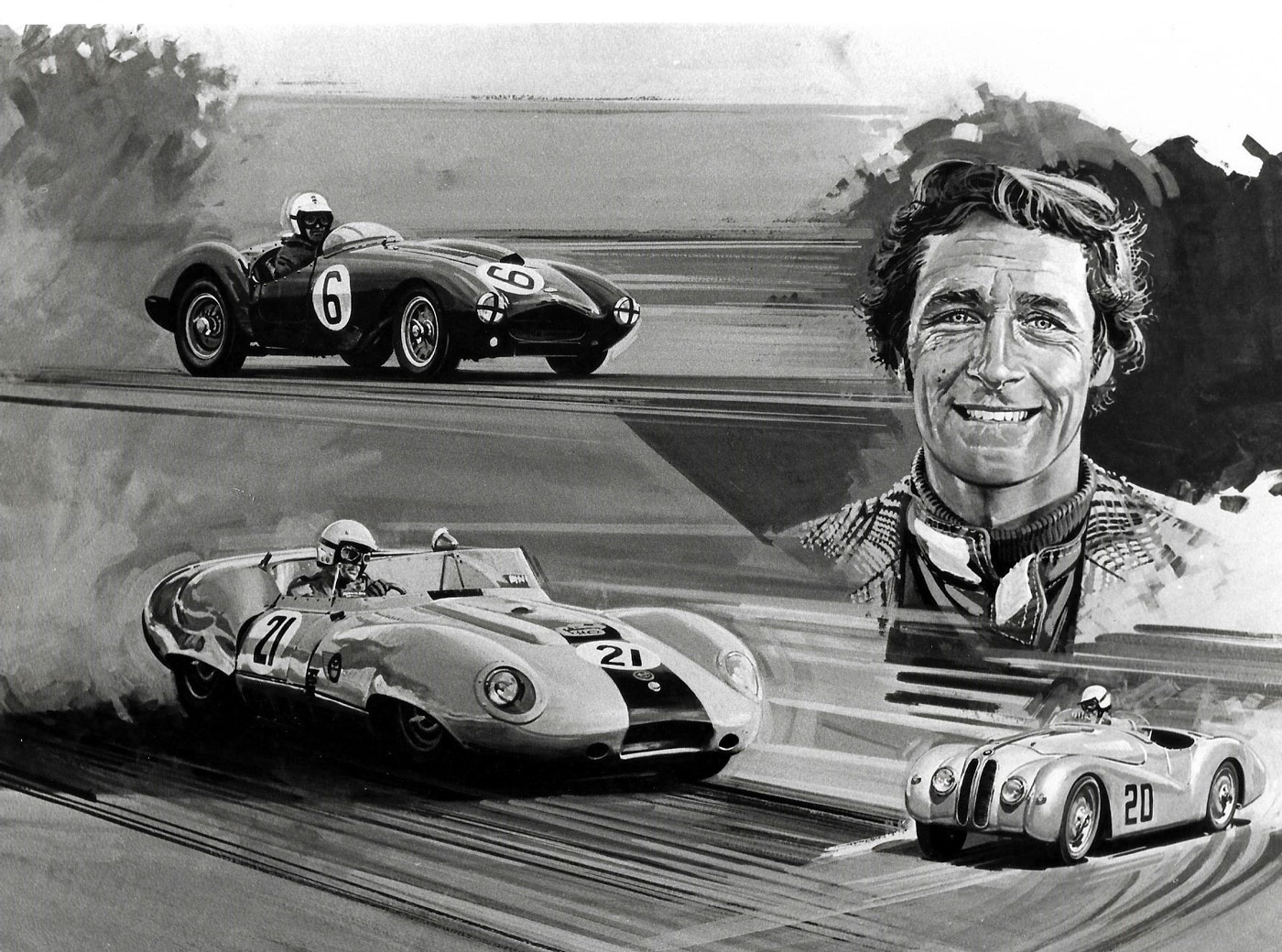

Michael Bowler was the first editor and brought a great deal to the fledgling publication. He was an excellent driver, and participated in JCB vintage race series for many years with a variety of interesting sports racers. In almost every issue Bowler would present a remarkably comprehensive marque history, often detailing Italian cars such as the Maserati 250F. Rodney Diggens caught a few of Bowler’s automotive adventures in this drawing which also appeared in TCC.

Michael Bowler commented on this Diggens’ montage: It was given to me by Rodney and Lionel as a leaving present when I left TCC and went to work for Victor Gauntlett at the end of 1980 – still much appreciated! Art by Rodney Diggens.

Writes Bowler, “While I had never set out to be a journalist, I happened to know two important people at The Motor – editor Dick Benstead Smith and publisher Harold Nockolds. Dick had read my newsletters to members of the Cambridge University Automobile Club, so was aware I could put words on paper. My interests then were firmly fixed on modern cars and all forms of competition. I was interviewed, employed as a road-tester and then had to learn to write and type back in 1963.

“I had been brought up on pre-war cars with my father, Harry Bowler, who was a Brooklands Bentley racer and then a VSCC committee stalwart. We went to all the vintage meetings after the war. Working on The Motor – it became Motor in 1964 – allowed me to keep modern cars as the job and retain old cars as the hobby. Most of Motor’s old car articles, including track tests, were mine over the next ten years.

“Then along came Lionel. I think it was at the 1972 Brighton Speed Trials that he cornered me and explained what he then had in mind for an old car magazine. We then began to chat on the back stairs of Dorset House where both Autocar and Motor were housed.

“It wasn’t an easy decision to make hobby and job into one. I had to give up a much-appreciated job as Sports Editor after just three years, but the challenge got me. We started work in a back room of Dorset House in July 1973. I knew nothing about putting a magazine together with page lists, balancing the features according to ages and types of car, contributors and their payments or even just writing a general editorial intro each month. Lionel knew it all, so I just did as I was told and we got along fine.

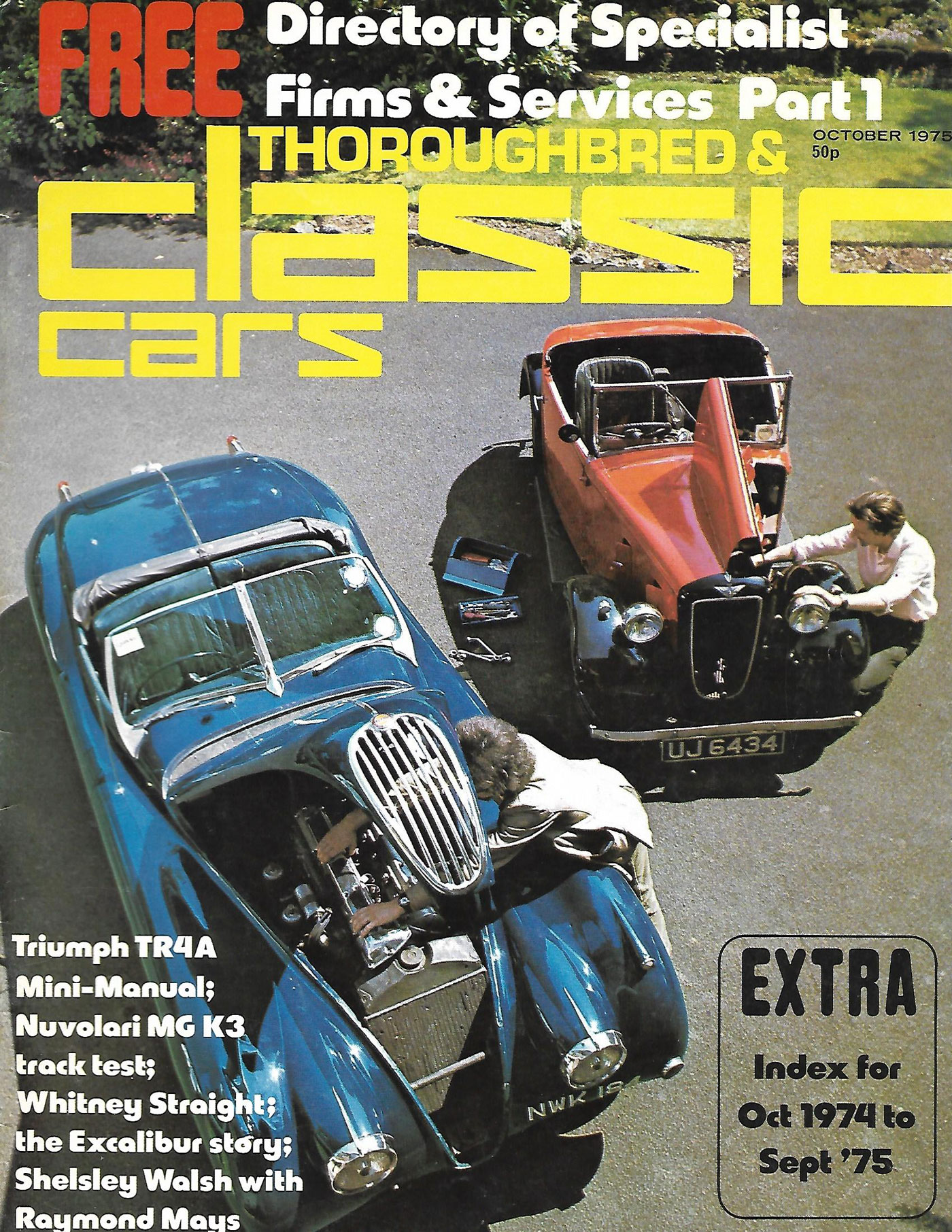

From the October, 1976 issue of the magazine. TCC photographer Paul Skilleter is seen at the left wondering what Burrell is up to with the ladder on Bentley KLY 3. Setting up for high angle photos, of course! Bowler learned a lot from Burrell, who in turn kept tabs on his crew of talented photographers, writers, historians and columnists.

“I enjoyed persuading Vintage and Classic owners to let me drive their cars on road or track and research their histories. Lionel was equally adept at steering Jonathan Wood, who had already earned a reputation as a class car writer. And it was Lionel who kept tabs on Graham Robson, one of our most prolific contributors, telling him what to write. While we were soon to have our own photographer in Paul Skilleter, we couldn’t have done without ready access to The Autocar photograph files as we shared a publishing director in Maurice Smith.

“We certainly made our own contribution to the world of historic racing, reporting on the ongoing JCB championship as well as the new breed of post-war classic racers found in the Historic Sports Car Club. It was fortuitous that the international historic racing scene had been taking off. The Nurburgring Classic had started the year before and the Le Mans Cinquantenaire had been run that June 1973. We were there and would continue to be so as I had exchanged my 1955 Frazer Nash Sebring for a 1959 Lister-Jaguar. It all helped to promote the magazine.

“One of the major indicators of the absence of a true classic car magazine was the classified advert section of Motor Sport. All that 1950s car advertising and nowhere to read about them. William Boddy would write on vintage car matters and there was always Veteran and Vintage, so our coverage of ‘30s and ‘50s had no opposition. Our circulation went up through 100,000 just as Motor Sport was descending through that landmark.

“The time had come for me to move to pastures new. I was spending more time with the sporting wing of the FIA for which our new Historic Commission, formed in 1973, had drawn up Appendix K regulations for all historic racing. I then resuscitated the engineering training I had and went to work with, then for, Aston Martin and Yamaha before eventually finding my way back to writing alongside Lionel and Jonathan for The Automobile.”

Jonathan Wood

“I started my motoring career on the Mercury House journal, Car Mechanics. In 1973, I was interviewed for a post on IPC’s Motor magazine, but was unsuccessful. However, I was invited to join Michael and Lionel as features editor on the shortly-to-be published Classic Car. My role would be discovering the people who had created the cars and telling their stories, such as Stanley Edge, the 18-year-old draughtsman who co-designed the original Austin Seven. IPC moved its offices from London’s Waterloo to Sutton, Surrey in 1981, and I decided to leave to pursue a freelance career, writing books and magazine articles.”

Rodney Diggens

Selling art to the staff at TCC was fun, and scary. Diggens recalls his initiation. “I can see myself entering the hallowed portals of Dorset House in Stamford Street London SE1 all those years ago, portfolio tucked under my arm and knocking apprehensively on TCC’s office door; needn’t have bothered knocking, my knees were making enough noise! I’d been doing this sort of thing for quite a while, knocking on doors, during that transition from employed printer to self employed freelancer. Needn’t have worried of course, they were all really great, their enthusiasm was completely infectious!”

Burrell of course was an artist as well so that was also intimidating. “Lionel liked what he saw and the rest is, as they say, ‘history.’ I did rather upset him on one occasion I remember, when an illustration of Jaguars included a 120 coupe with wire wheels and knock-off hubs, had spats over the rears! A terrible oversight and unfortunately it was published!”

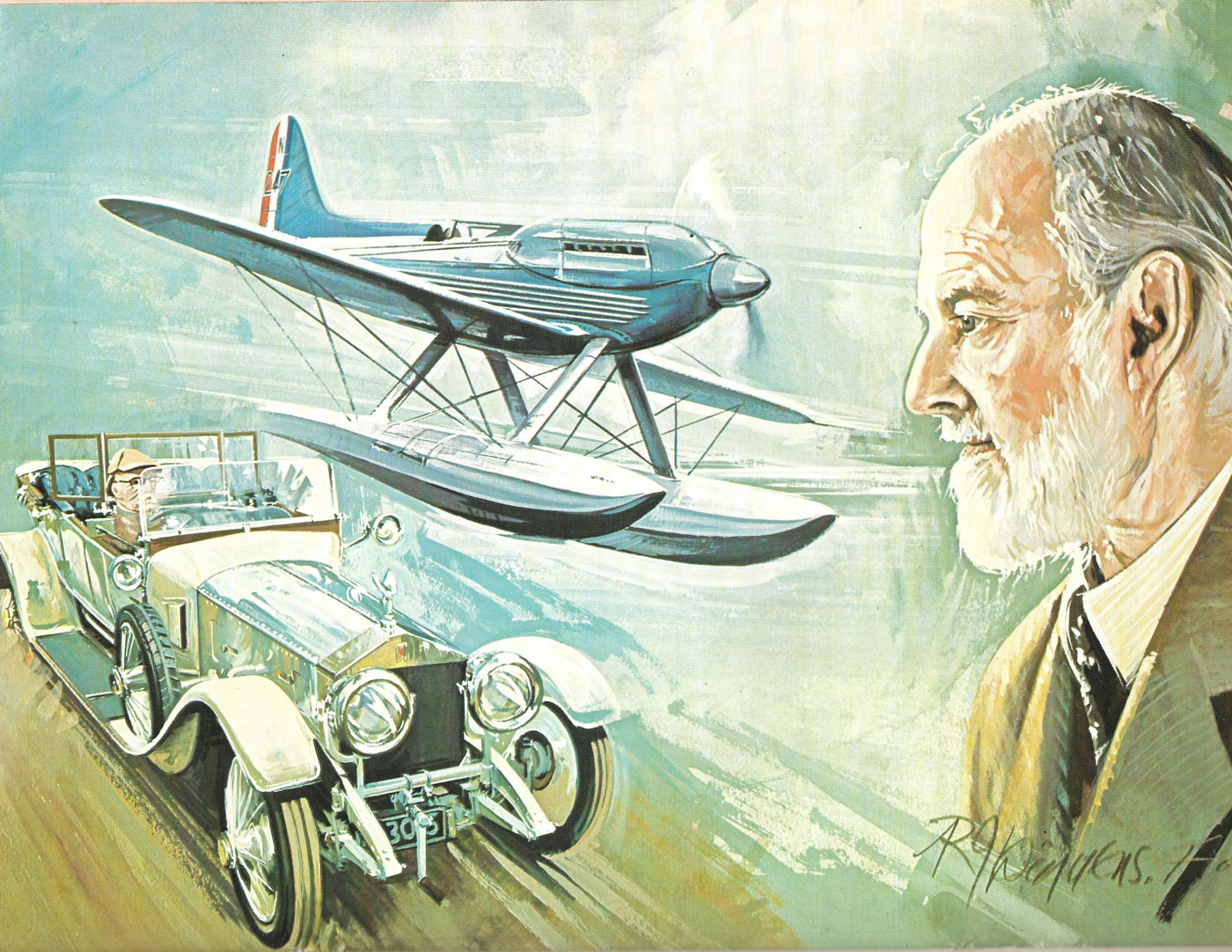

Diggens combined his interest in aircraft and cars in this tribute to Sir Henry Royce in the December, 1979 edition of TCC.

Ready or not, at TCC Diggens was immersed into the classic car scene. “I remember when Jonathan Wood wondered if I’d like to join his team of judges for Concours d’Elegance awards at various meetings around the country. The rules were very detailed and direct so provided you followed them to the letter you ought to survive; owners could get very upset at any criticisms! I’d always park my rather battered Vauxhall Cavalier well away from the judging arena!”

Diggens’ take on Bowler: “Michael is a really nice bloke. He was always very friendly and helpful towards me. He allowed me access to that fabulous photographic collection at Dorset House. He introduced me to Victor Gauntlett, who bought and commissioned work. I certainly remember watching him racing, especially with his Lister Jaguar.”

Looking back, this writer is still amazed at the depth and quality exemplified by Burrell’s new magazine. Everything was old but new, fresh, accurate and presented with great enthusiasm. We had so much to learn, so many questions, and such a thirst for knowledge. TCC satisfied those needs. We owe a good deal to the guys that made it happen.

What a lovely piece of writing, I’ve found out a lot about my Dad.

Kind regards

Nicola

When I discovered this magazine on a Denver newsstand in the 1970s, I was blown away by its broad coverage and high quality. I subscribed immediately then started collecting all the back issues, which still grace my library.