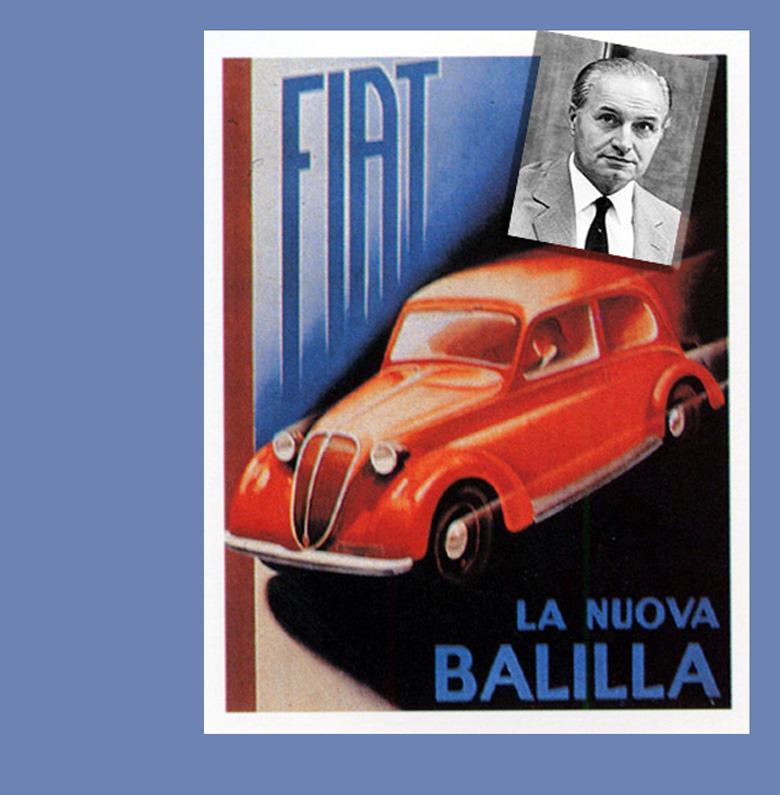

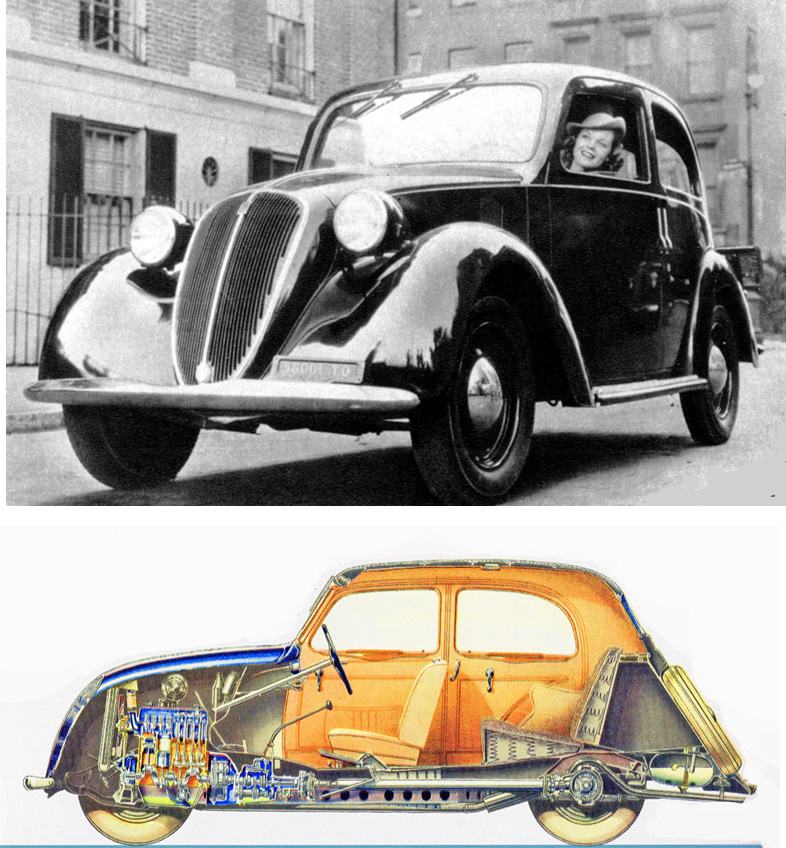

First called the Nuova Balilla, the new Fiat quickly became the 1100, or Millecento as the Italians called it. Inset: A 30-year-old engineer named Dante Giacosa was responsible.

Eighty years ago, in November 1937, Fiat introduced its first 1100 cc four-cylinder engine with overhead valves. This small, mass-produced engine not only powered a great number of Fiat’s bread and butter automobiles, but also became the heart of many exciting Italian and French specialist sports and racing cars. This article covers the years 1937 – 1940.

Story by Gijsbert-Paul Berk

In 1935 Italy was in the middle of a controversial colonial war in Abyssinia. In Turin that same year, Antonio Fessia, the manager of Fiat’s engineering department, asked the thirty-year-old engineer, Dante Giacosa, to develop a successor to the popular Balilla model. Giacosa had earned the respect of the Fiat management for his brilliantly designed 500 model, nicknamed Topolino (little mouse). Fessia explained that the new car should fill the gap between the small 500 and the recently introduced flagship of the Fiat range, the modern six-cylinder 1500 model.

A new challenge

As Giacosa describes in his autobiography Forty Years of Design with Fiat, Fessia wanted him to design simultaneously two engines: a four-cylinder and a six-cylinder, both with the same cubic capacity.

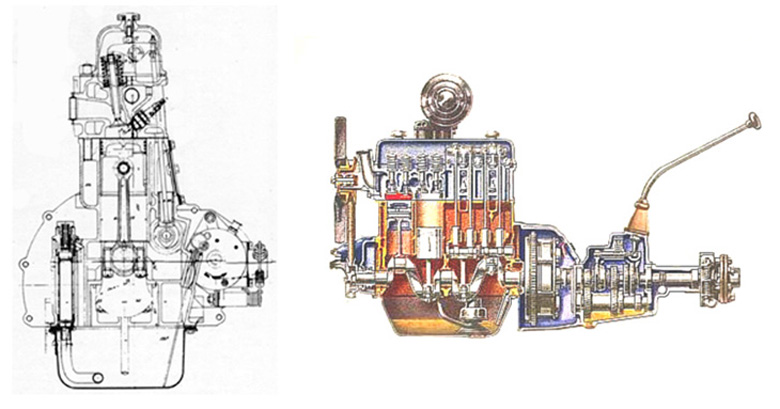

Cross sections of the 1937 Fiat 1100 engine and drive train. The new four-cylinder OHV engine was a very straightforward design. It had a three main bearing crankshaft and two valves per cylinder, which were operated by pushrods and a single chain driven camshaft in the cylinder block. Basically, the bottom half of this new engine was so similar to that of its side valve predecessor that it could be produced with practically the same molds and machine tools. But the new designed light metal cylinder head with overhead valves and the increase in cubic capacity (from 995cc to 1089 cc) made all the difference: 33% more power! (Illustration courtesy Fiat)

Aided by a team of about fifty draftsmen, he started on his task. “Our reference for the new engine was the ohv version of the 995 cc/508CS engine which was fitted in the Balilla Sport,” explains Giacosa. For an outsider, this replacement seems somewhat surprising – the 1492 cc six-cylinder of the Fiat 1500, which had been in production since 1935, already had overhead valves. But the engineers had to bear in mind that Fiat’s factories were equipped with the machines and tools to manufacture the 4 cylinder Balilla side valve engine. Since 1932 Fiat had produced 132,130 of these units.

“Therefore the choice makes economic sense.” Giacosa continues. “We increased the diameter of the cylinders (bore) to 68 mm. In the design, special attention was given to the shape and size of the combustion chambers, and to the position of the spark plugs. Our objective was to achieve a rapid progressive combustion.” In addition, the head was cast in aluminum.

“In accordance with my instructions,” wrote Giacosa, “we designed at the same time a six-cylinder. Being lower it permitted a lower bonnet and better streamlined front of the car, but being longer it needed a larger chassis. This engine was also substantially more expensive to manufacture; the four-cylinder configuration won the day.”

Experiments with independent suspension

After many experiments and studies of the ingenious Dubonnet suspension, which was used on the first 1500 series, Giacosa decided to design a totally new independent suspension system with coil springs, which would cost less to manufacture than the Dubonnet units. With this new configuration, he not only solved the vexing ‘shimmy’ problem that affected the Dubonnet system, but saved weight as well.

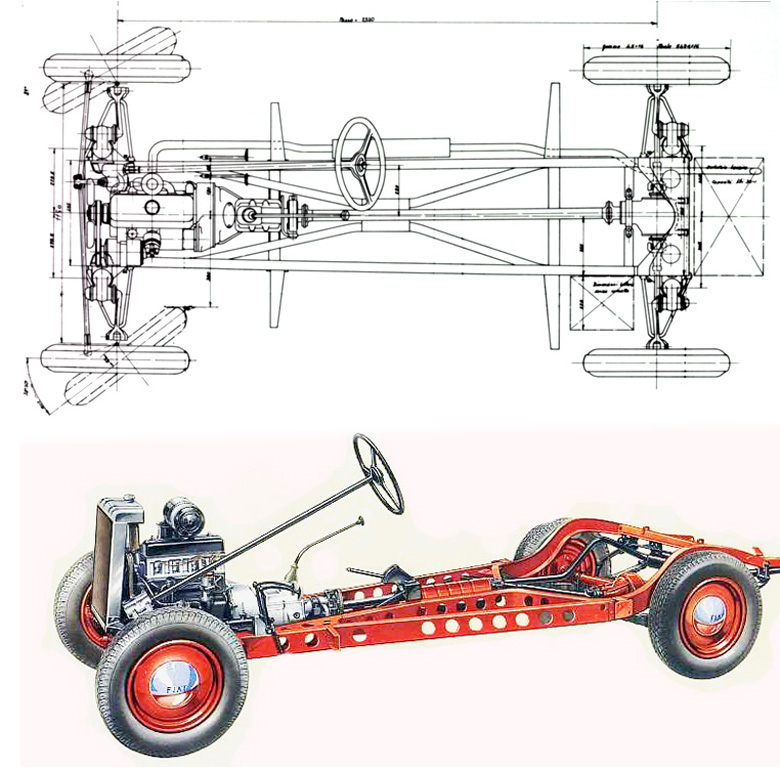

What might have been, with both independent front and rear suspension, top. Final product, conventional but well designed, bottom. For the chassis frame Giacosa chose a similar construction he had used for the 500: longitudinal members with large holes for lightness, flexible in itself but sufficiently rigid when the all metal body that was bolted onto it.

(Illustration courtesy Fiat)

However, road tests showed that the advantages of independent rear suspension did not justify the complications and the increased production cost. Giacosa abandoned his original idea to have independent suspension fore and aft and retained a conventional live rear axle and leaf springs.

Family resemblance

With its rounded roofline and heart shaped, sloping “waterfall” radiator grille, the 1100 Balilla looked like a slightly scaled down version of the 1500; not surprising, because that car was the Italian interpretation of the new fashion of “streamlined” automobiles, which had been pioneered by Chrysler’s Airflow, among others.

The shape of the 1500 was born on the drawing board of Mario Revelli di Beaumont, who then worked in the Special Coachwork department at Fiat. A mock-up of the design was tested in a wind tunnel to verify its aerodynamic qualities.

Mario Revelli di Beaumont later became a consultant to companies like Fiat, Bertone, Ghia, Pinin Farina, Stablimenti Farina, and Viotti. He was also a teacher at the School of Art and Design of Turin and at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena (California).

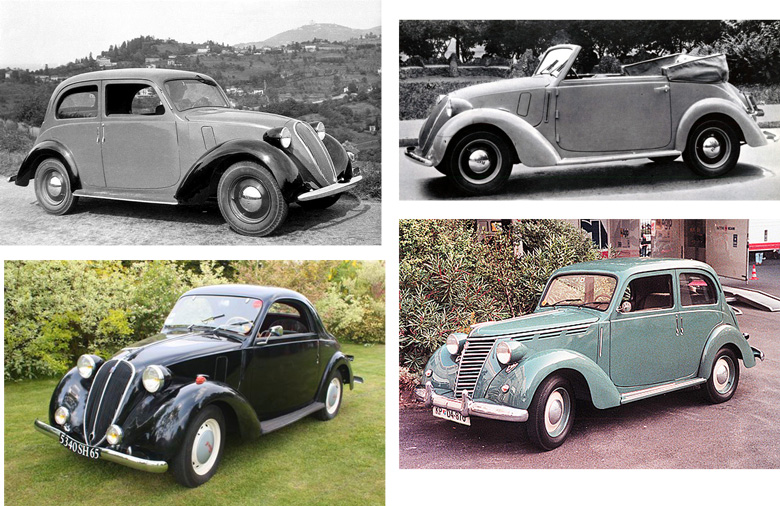

Top Left: One of the first official Fiat publicity photos of the new 1100 508C. Top Right: The 1100 had several variants, here the popular convertible. Bottom Left: Smart Simca 8 Coupé. Fiat and Simca both marketed a two door coupé and cabriolet model on the 1100 chassis. This Simca version had a windshield that was hinged at the top and could be opened slightly to provide better ventilation on hot days. Bottom Right: By the end of 1939 the Fiat 1100 was subjected to a face lift. American influence? (Illustration courtesy Fiat)

Simca and Fiat

The new Fiat 508C, or Balilla 1100, was presented at the 1937 Milan Motor Show. That same autumn the car made its debut at the Salon de l’Auto in Paris as the Simca 8. Mechanically the Fiat and the Simca were indeed twins. This similarity was understandable, because Simca (Société Industrielle de Mécanique et Carrosserie Automobile) was founded in 1934 in Suresnes near Paris to build Fiat cars in France and so circumvent the sky-high French import duties.

Italian and French rivals

Lancia also chose the 1937 auto exhibitions in Milan and Paris to launch its four-door Aprilia (Ardennes in France). With its monocoque body, independent suspension all round and equipped with a modern 1352 cc V4 ohv engine, it was without doubt a trendsetting newcomer. However, it cost roughly 45% more than the Italo-French Millecento. In January 1938 Peugeot unveiled its 202. This had a 1133 cc ohv four-cylinder engine, independent front suspension, and was technically and price wise a more serious rival. The four-door body was shaped in the same fashion as the Fiat/Simca, but its headlights were protected behind the sloping grille.

Favorable reviews

Top: The Topolino was popular but the Millecento more useful. Giacosa had another hit on his hands. Bottom: Under the skin the Fiat 1100 and the Simca 8 were identical. (Illustration the French Revue Automobilia)

The 1100 Balilla and Simca 8 were well received and the articles in the critical motoring press were favorable. The simple, but effective, independent front suspension gave the Fiat/Simca predictable and safe road holding. Compared to the previous generation they also provided a larger interior and a comfortable ride for their passengers. In those days, most of popular mass-produced European cars were still powered by sluggish side valve engines. Most had only three forward gears. Therefore, a four-door, four-seater saloon with a dry weight of only 850 kg, powered by a peppy, modern four-cylinder engine with overhead valves combined with a well-spaced four-speed gearbox and a top speed of 110 km/hr (68 mph), was considered an important step forward in this category. In fact, as historian Michael Sedgwick put it, “The Millecento was “a thoroughly modern mille,” which was a reference to a popular play of the time.

Even if the 1100 Balilla did not have the charm of the endearing Topolino, it was clear that Giacosa and his team had again created a bestseller. Up to 1948 Fiat would produce 148,000 units of this newcomer against 122,000 Topolinos. But what only a few technical specialists at the time noted were the promising specifications of the new 1100 engine: with a bore and stroke of 68 mm x 75mm (2.68 x 2.14 inch), it had a bore/stroke ratio of 0.91 and a cubic capacity of 1089 cc (66.455 cu in). The compression ratio was only 6:1, which permitted use of lower grade petrol). Fiat claimed that at 4000 rpm the small engine developed 32 HP (24 kW).

Competition potential

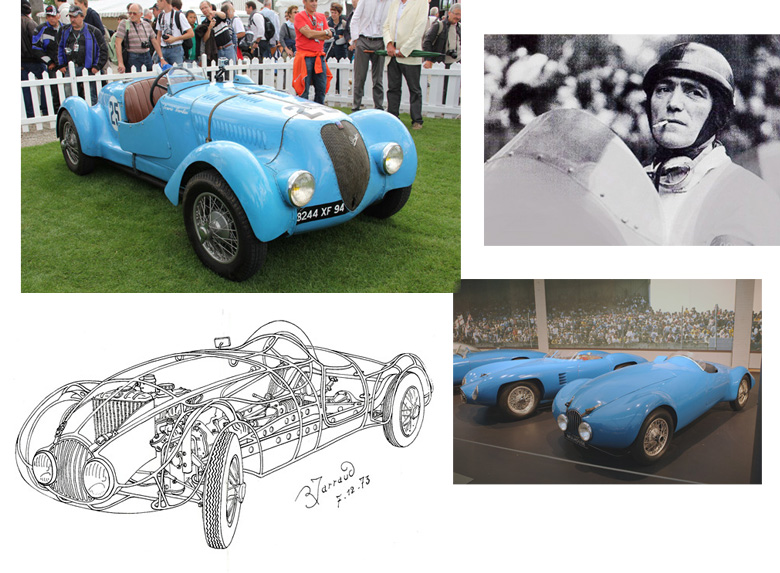

One of the first to spot the competition potential of the new 1100 engine was Amédée Gordini. This gifted Italian born technician and racing driver operated a workshop in Paris specializing in tuning Fiat and Simca cars. He was also a talented driver who regularly won races and rallies with his Simca based sports cars. This led to a friendship with Henri Pigozzi, who was the CEO of the Fiat/Simca assembling plant in France. Even before the presentation at the French Motor Show, Pigozzi arranged a preview and a trial run of the new Simca 8 for Gordini. Gordini was impressed and immediately started the construction of a sports car using this new engine. By carefully preparing the various components, raising the compression ratio and replacing the standard carburetor with a Solex 35 AIP, he managed to increase the maximum power output from 32 to 60 HP.

Top The streamlined version of the Simca Huit by Gordini created in late 1937. This is chassis 823 885 which was first in class at Bol d ‘Or on June 6th 1938. AmédéeGordini, race driver. Bottom: The famous Simca Huit Gordini 810404 T8 which won the Index and class at Le Mans in 1939.

In June 1938, together with his co-driver José Scaron, he participated with his streamlined Simca-Gordini ‘tank’ in the 1.1-liter class of the Le Mans 24 hours race. Unfortunately, they had to abandon after 140 laps (1,988.880 km), but a few weeks later they won the Paris-Nice Rally. In the 1939 Le Mans event, the same Simca-Gordini team and their ‘tank’ were first in their class and won the Index of Performance. (read about PreWar Gordinis.) (read about PreWar Gordinis.)

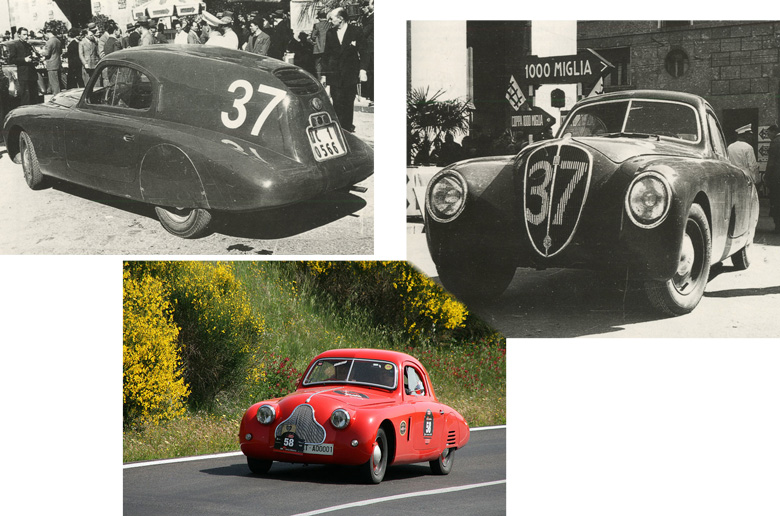

Fiat’s Mille Miglia contender inspired by a delivery van

In the meantime, Giacosa himself was developing another sporting derivative of the 1100. In his biography, he calls the MM coupé one of the most interesting sport models, because its superior performance was mainly achieved through a careful study of its aerodynamics. During tests with a prototype for a van on the chassis of the small Topolino, the design team discovered that the van was faster than the standard two-seater.

This unexpected revelation was a quarter of a century before Ugo Zagato discovered the same Kamm effect. Giacosa realized that the van had lower air resistance and this recognition led him to pay special attention to the shape at the rear of the coupé they were preparing for the Mille Miglia. They made a number of 1:5 scale models which were submitted to test in the wind tunnel which had been set up by Professor Panneti of the Turin Polytechnic. These tests confirmed the form having the lowest air resistance.

Top: One of the first public appearances of the Fiat 1100 MM coupé was at the start of the 1938 Mille Miglia in Brescia. This car was manned by the team of Casalegno-Di Rovasenda and was one of seven 1100 Fiats to be entered in the 1938 Mille Miglia. One can imagine that at the time its shape created mixed reactions. Some called it the Fiat Gobba (hunchback)

In color, the 1939-40 version of the 1100 MM Fiat.

One objective of the MM l’indice de performance was to provide a publicity boost for the 1100cc 508C by participating in competitions. This condition implied that the coupé had to use the standard chassis, which prevented the designers from making the coupé much lower. To achieve the lowest possible ‘drag’ the shoulder room inside the cockpit was sacrificed as well as the rearward visibility. Just like the BMW 328 coupé, which Carrozzeria Touring made for the 1938 Mille Miglia, the Fiat MM belonged to the first generation of sports cars with a ‘pontoon’ body (no separate mudguards). Fiat outsourced the series-production of the MM coachwork to Savio, one of the many specialist body shops in Turin. Antonio and Giuseppe Savio were first class craftsmen, who used aluminum for most of most of the non-stress bearing panels and thereby reduced the weight of the car to 820 kilos. The power of the 1100 engine was increased from 32 to 42 HP at 4400 rpm by raising the compression ratio to 7:1 (the maximum possible with the then available petrol in Italy) and using a different carburetor (a Zenith 32 VIMB). The combination of a higher power output and a lower air resistance resulted in a top speed of 140 km/h.

Fiat’s participation in the Mille Miglia was highly important. For many years, the Mille Miglia in Italy and the 24 Hours of Le Mans in France counted in Europe as the most important international races for sports cars. During the pre-TV years following WWII, the Mille Miglia became a favorite Italian spectator sport. Tens of thousands ‘aficionados’ stood or sat for hours on both sides of the roads along the route from Brescia to Rome and back This event was comparable with football, the Giro d’Italia, the annual bicycle race traversing their country, and the Grand Prix at Monza.

In the 1938 Mille Miglia a Savio bodied Fiat MM coupé, driven by Taruffi and Carena came first in its class and 16th overall, setting a record breaking average speed of 112 km/h. In that event, no less than 58 cars used the new Fiat 1100 engine. Some were more or less standard saloons; others were purpose-built specials prepared by firms such as Savio, Siata, Stanguellini and Viotti.

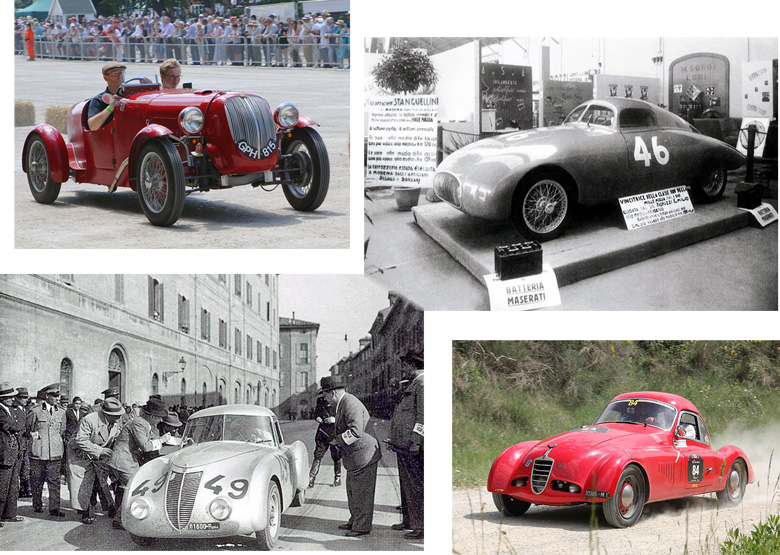

Other prewar 1100 Sports

In addition to Gordini and Fiat itself, the new 1100 was a instant success with tuners and small race car builders. In the UK, V.H. Tuson, already well known for his success with Balillas, immediately constructed a lightweight body on the 1100 chassis and raced it at Brooklands. In Italy, the introduction of the Millecento corresponded with the creation of the Italian Championship for Sports, which sanctioned four displacement classes for sports cars at many Italian events. These classes were: 750 cc, 1100 cc, 1500 cc and over 1500 cc.

Top Left: Back in the UK, V.H. Tuson, known for his exploits at Brooklands with Fiat 509s and Balillas, quickly upgraded to a new 508C, creating one of the first 1100 Specials. Here at Brooklands in 2017. Top Right: Publicity photo of the 1940 Fiera Campionaria in Modena (the yearly festival and trade fair), where the local Fiat dealer and sports car manufacturer Stanguellini, proudly presented its Mille Miglia car. Of course powered by a Stanguellini tuned Fiat engine. Bottom Left: A Fiat 1100 powered Viotti Berlinetta at a checkpoint during the 1938 Mille Miglia. Bottom Right: Siata (for Società Italiana Auto Trasformazioni Accessori) started as a tuning shop and manufacturer of performance parts for Fiats. But they also build cars. Here we see the Siata 1100 Berlinetta Aerodynamica, designed for the 1940 Mille Miglia.

Sources: “Forty years of Design with Fiat” by Dante Giacosa, “Cisitalia” by Nino Balestra & Cesare De Agostini, “Gordini, un sorcier, une equipe” by Christian Huet, several issues of the Hors Series edited by René Bellu and published by the French magazine “Automobilia” plus websites and Wikipedia pages. The latter were very useful to check race results.

Acknowledgements: Images courtesy Fiat, Hugues Vanhoolandt, Jonathan Sharp, French Revue Automobilia

Next: 1940-1950

Read the entire seven part series!

Formidable article !!!

Avec dates et carrossiers, ce qui devient rare, même chez vous ……….

Hervé

I found this a fine piece of history that has been neglected before

So interesting of FIAT and SIMCA 8 derived, and the wonderful

Mille Miglia connection. Well done !

Jim Sitz

Appreciative of the history, research & collaboration. Thanks to all.