Review by Pete Vack

Photos from the book courtesy Peter Larsen

On March 21, 1942, Jacques Kellner (owner of one of the greatest French coachbuilding firms), Georges Paulin (automotive inventor, designer), Robert Éntienne (shop foreman at Kellner Carrosserie), and Roger Raven (metal worker at Kellner Carrosserie) were tied to a post and shot to death by the Germans for acts of espionage. At the same time, Aileen Schoofs was sentenced to five years in prison for her role in the espionage.

They were all members of a French Résistance spy cell known as Phill.

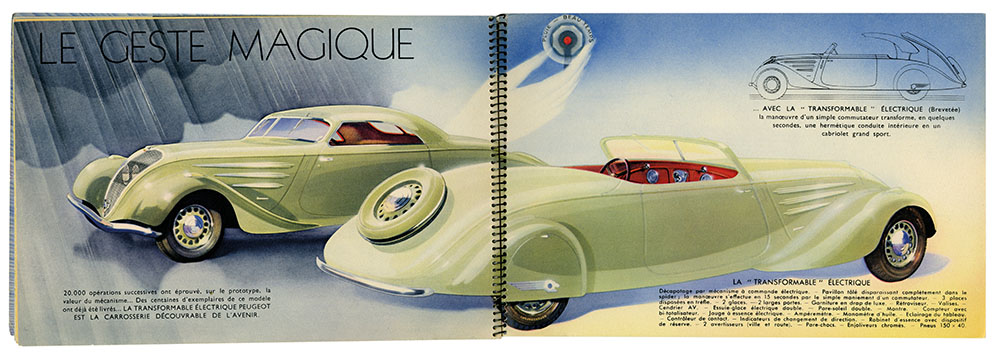

Georges Paulin may be best remembered as the designer of the transformable hardtop. He was also a French Résistance hero.

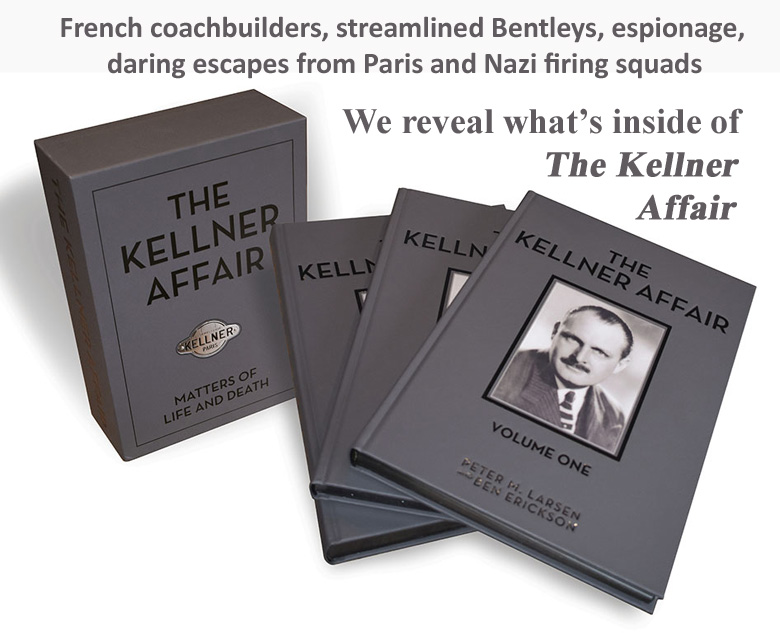

With an overabundance of motivation, time, energy, focus, and documentation, Peter Larsen and Ben Erickson have told the story of these French resistance heroes as completely as possible, leaving no pebble unturned. While the story of the Kellner ‘affair’ has been previously published in a variety of sources, Larsen has found new official German and French documents, family remembrances, photos and memoirs to create an updated, comprehensive and exciting true life spy story about the Résistance in occupied France. It is also so well illustrated that one can lose sight of the narrative. But how many non-fiction spy thrillers are so well presented with hundreds (there are 1,568 printed images in the three volumes) of contemporary photos of the streets, buildings, countryside, cars, people, and background, shedding light on both the tragedies and adventures.

Along the way Larsen writes of the history of the Kellner Carrosserie, Paulin’s role in the creation of the Embiricos Bentley, and the close-knit group of people involved in the automotive industry who played a role in supporting the various espionage cells. The subtitle to Volume 1, “Matters of Life and Death” indicates that these volumes will not concentrate on the frivolities of the rich and their stylish automobiles.

Evocative photo of a dying age. June 24, 1938, Princess Stella of Karpurthala behind the wheel of the Figoni et Falaschi Talbot Lago at the Trocadéro. Larsen writes “A perfect cameo of what once was. Who cares that she was born Stella Mudge and used to be a dancer at the Folies Bergère?”

To give the reader a better understanding of these agonizing times, Larsen and Erickson tell us about the sinking of the French Navy at Mers-el-Kébir by the British Navy in July of 1940 and the awkward consequences that followed, the formation of the French Resistance, the collaborators, the heroes and the politics. With great research, insight, and a bit of speculation, Larsen sets a multi-layered stage. He does so with a considerable amount of talent, making his readers care about each subject and to wonder about their fates. His ability to handle the complex social and military history with multiple characters while reading French, German and English is astounding.

Walter Sleator plays a major role in the book. He was the Director of Franco-Britannic Automobiles in Paris, brother to Aileen Schoofs, and managed the Alibi and Phill cells from Madrid during the war.

He writes in depth and often takes us on paths we can’t at first fathom. Why are we reading about the jet-powered Messerschmitt? Whatever does the bombing of a Shell building in Copenhagen have in common with anything? And who cares about Violette Morris (a.k.a. The Hyena of the Gestapo)? Just when you think you have been led astray, you find that most everything leads to something in an intricate plot that thickens as the story progresses. As the list of characters is fairly long, the author has thoughtfully provided a list of characters and people, which we found very useful.

With great research, insight, and a bit of speculation, Larsen sets a multi-layered stage. He does so with a considerable amount of talent, making his readers care about each subject and to wonder about their fates.

Larsen first became interested in the Kellner affair as he was writing his work of Jacques Saoutchik, a French Jew who was labeled (incorrectly as Larsen would uncover) as a collaborator after the war. He then began a similar work on Figoni and Falaschi, and the Figoni saga kept including references to Jacques Kellner and the Phill group. He put aside the Figoni manuscript and concentrated full time on Kellner. In addition, Larsen had his own story that kept the fires burning. His father was a member of the Danish Résistance, and was tortured by the Nazis during the war. He lived to tell the tale but rarely spoke of it, leaving it to his son to delve deeply into the past looking for answers and details. Larsen is a driven man.

In February of 1938, Walter Sleator and W.A. Robotham took the Paulin-designed Embiricos Bentley to Germany for tests on the Autobahn and averaged 112 mph for five minutes. Sleator in the sailing cap.

This is an unconventional book in three volumes. The first question one might ask, is a lengthy sojourn about the occupation of France and the resistance relevant to a book about French coachbuilders and designers? The heroism and death as a spy is certainly relevant, but to this extent? Larsen would argue that the full story must be told, but an editor might argue otherwise. It is a probably the one and only time that such a story has a chance for publication, might as well go the whole nine yards and be done with it, or so the author might argue.

The text also deals with other members of the resistance, such as Jean Boutron, a dashing French naval officer who devoted his wartime years to assisting the resistance network, Marie-Madeleine Fourcade, who is perhaps the greatest heroine of the French Résistance. Walter Sleator, who acquired a Rolls-Royce dealership in France and worked with Kellner and Paulin on various prewar projects, was, like his sister Aileen, a member of Phill and worked from Madrid during the war. Sleator recruited both Kellner and Paulin, who would be asked to set up a radio transmitter from Paris, an effort that would lead to their execution.

Volume 1 begins with In Memoriam, Introduction, Notes on the Collaboration and Resistance, A Note on the Title, Dedication (to his research assistant) Acknowledgment and Sources, and a Prologue. Larsen goes to pains to explain what he is doing and why, and is not shy to include everyone who helped him. Chapter One is, somewhat surprisingly, ‘The Rise of Aerodynamics’, a feast for the car enthusiast. This in turn leads to several chapters on the stunning Embiricos Bentley as many of the characters are linked by the creation of the first streamlined Bentley, designed by Paulin inspired by Jean Andreau. A too-short history of the Kellner Carrosseries follows before the author gets deep into the fall of France and the development of the Résistance.

Larsen finds a photo for every character in the book. Here is a postwar photo of a true Résistance hero, Marie-Madeleine Fourcade.

Volume 2 tracks the arrest and deaths of Kellner and Paulin, as well as the arrest and incarceration of Aileen Sleator Schoofs, Walter’s sister who was married to his good friend Jean Schoofs, both involved with Phill. Larsen describes in detail, with numbered photos of the journey, how Jean Boutron literally stuffed both Jean Schoofs and Marie-Madeleine into a Traction Avant and brought them both to safety from France to Madrid in a harrowing wintertime journey. These adventures are tangential to the story of Kellner, the connection being that all had a role in the French espionage network and knew each other. Larsen explains, “The post-execution story about Jean Boutron and Marie-Madeleine Fourcade lay the groundwork for explaining how and why Walter Sleator was able to take over Franco-Britannic Automobiles so ignominiously after the war. And more importantly, it clears the name of Jean Schoofs who for decades has been fingered in France as the traitor who denounced Phill. This alone is perhaps the single most important new truth in the book.”

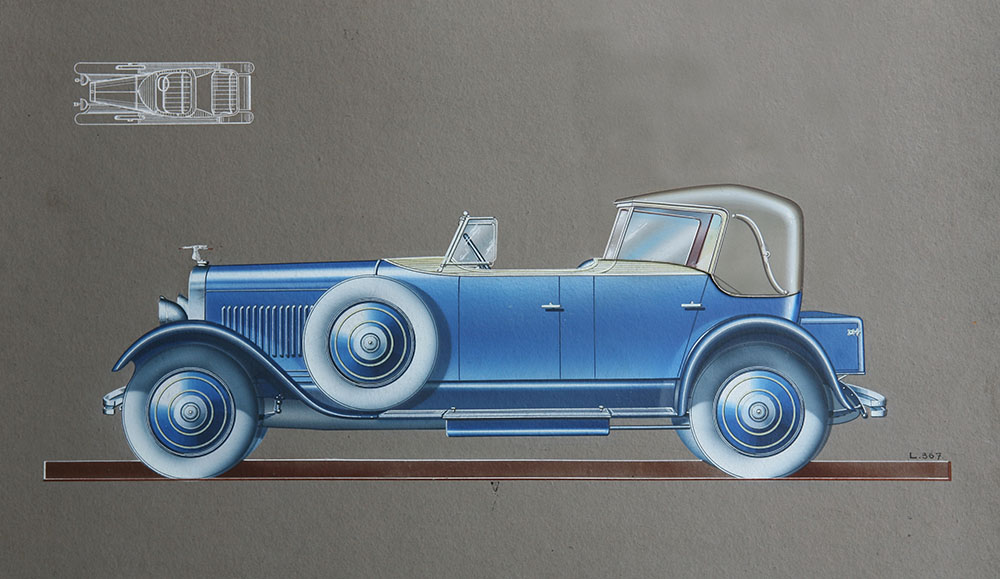

The spy thriller over, Larsen devotes Volume 3 to documentation, even including a USB flash with further documentation, mostly French and German. But then comes a Portfolio of Kellner Design Drawings, which includes blueprints, brochure renderings and drawings enough to warm the heart of any French car enthusiast. “…here’s your fix”, writes Larsen.

The drawings, brochures and photos of the Kellner designed cars are superbly reproduced. Kellner made few car bodies after 1935 and diversified.

This is followed by a Portfolio of Cars Bodied by Kellner in alphabetical order. Neither is complete of course, but a good cross section. But Hispano Suiza fans will be astounded by the number of Kellner-bodied cars in this section, including one made by Skoda Hispano Suiza H6Bs. (Skoda made about 100 under license). The Renaults, and Rolls-Royces bodied by Kellner up to about 1935 are well-illustrated. More than half of Volume 3 is devoted to Kellner and well worth the wait.

Speaking of diversions, allow us one. This photo was in the book but did not explain that at the Monte Carlo Rally in 1949, Louis Chiron accused Hellé Nice of being a Gestapo agent. ‘Vôtre place n’est pas ici, vous’, said he. It was never proven but the accusation ruined her life. Here is Nice with an Omega 6 in 1929.

His handling of history is, overall, superb and on par with the work of academically trained historians. Of course we have some quibbles. We asked Larsen (who has a Ph.D. in English linguistics and semiotics from Brown in Providence, Rhode Island) to comment on our criticisms below and included his responses in italics:

1. Inopportune juvenile remarks about the Nazis (however accurate) demean the text as unprofessional. Everyone knows Nazis were evil, but such comments are unworthy.

I deliberately do not keep dusty historical distance and reserve the right to call a spade a spade. I wanted the book to read almost like a novel and not like a doctoral thesis. I want people to feel the emotion. I am also not particularly flattering to Maréchal Pétain, Charles de Gaulle, various French generals and politicians, etc. so I think I dispense my vitriol pretty evenly. It is also important that younger generations – if any young people ever read my book – are not left with a feeling that the Nazis were pretty nice people, OK dudes after all, and just like us. They were not. I have written this book lest we forget.

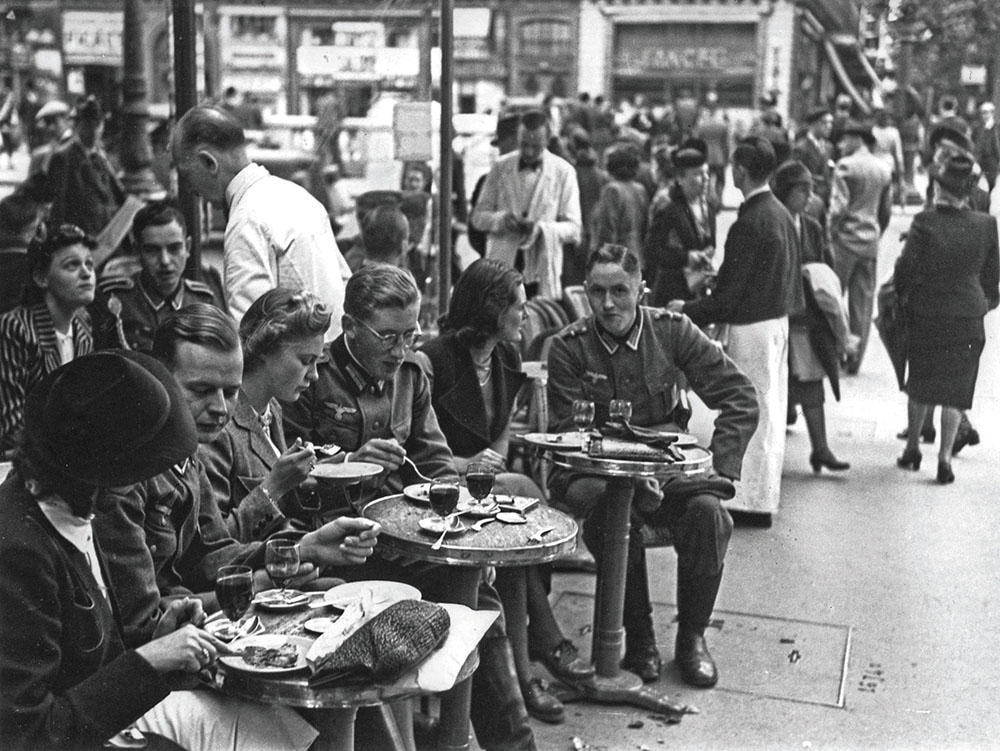

2. While many Nazis were indeed evil personified, the German army, as a whole, was well behaved throughout their occupation; they could have widely raped, robbed, bombed and pillaged – one looks to what happened as the Russians took over Berlin for contrasts. Larsen tends to lump all the German officers and soldiers as Nazis, which most were not. (Larsen does note that Paris was not put to the torch, as Hitler demanded.)

It is a popular and dangerous ratiocination these days that hardly any Germans were Nazis that a majority of innocents were caught up in the tide. This thesis is simply not true and it is a dangerous modern distinction to make. And even if it were true, it does not matter as the enormity of the deeds speak for themselves. By that token, if you wore the uniform, pushed the button that dropped the Zyklon B canisters in the showers of Auschwitz, flew the bombers, shot the guns, you were a Nazi, no matter what lies you told yourself and the world after the collapse of the Reich. Further, I come from a country that was occupied by the Germans, and the idea that they were personable occupiers that behaved nicely is another pernicious untruth. The very concept of a well-behaved invader is absurd, as I think Danes, Norwegians, Dutch and French will agree.

3. No footnotes. If a historian (or someone attempting to create a serious work) wants to be taken seriously, footnotes are a must. That said, facts in the book are well documented, even if it is not always easy to pinpoint the source. A necessary pain.

This criticism was also leveled against me with the Talbot-Lago and the Saoutchik books. It is a fair criticism, and not to have footnotes is a deliberate decision on my part. I simply hate the things. I provide copious bibliographies and I lay out all my reference material on the USB.

4. While providing a great deal of divergent background, Larsen does not, however, even mention two other heroes of the French resistance, Grover Williams and Robert Benoist, both of who were also executed by the Germans.

Many were executed by the Germans, and some of them were racing drivers. I could have included the two, but there is no reference (to my knowledge) that they were connected with Phill, Alibi or Alliance. To include them just because they were racing drivers and executed is a spurious connection.

German soldiers and French women during the occupation. The question was, what is collaboration? No simple answers.

We noted with pleasure that the books contain a glossary of places and terms, nomenclatures, a full bibliography, and detailed index.

The verdict? A supreme, worthy effort weighed down by detailed diversions and documents; a masterwork flawed by lack of restraint. Yet it’s all here, for the first and probably the only time. Take it as it is and be happy, for over the years, we have all wondered what our automotive heroes did during the war years. Concerning the activities of certain French carrosserie, Larsen has answered that question in a definitive and unforgettable fashion.

Luxurious hardbound edition (includes bonus material on USB)

ISBN regular edition 978-1-85443-291-9 US$445

Limited to 1,000 numbered copies signed by the authors

3-volume leatherbound in a solander box (includes bonus material on USB)

ISBN Deluxe editon 978-1-85443-296-4 US $1,950

Book size: 219 x 304 mm

Page count: 1,056 / Flash Drive: 401 pages

Total printed images: 1,568 / Flash Drive: 388 images

Here is an interesting question to mull over with the advantage of hindsight.

If a Parisian women with a young child who is Jewish, hides her daughter in a convent

and befriends a Nazi officer which gives her protective cover and avoids the random stops and searches by the Melice and the Gestapo, either of which would have consigned her to a death camp “in the East”, was she a ‘collaborator’? Certainly her fellow Parisians who were not Jewish, would have treated her so at war’s end and shaved her head. But how was she to be judged with hindsight, if at all?

Hard to imagine living through those times.

It is difficult not to become emotional reading the first two volumes, so much so that for me it was a bit of an uplifting moment when I read volume three. Hard to speculate how much time went into the research for this book. Parts I found to be overwhelming, but without a doubt informative and a bit of a historical eye opener for me.

When you tell us the key figures were shot to death, you expose the punch line of the book, you take the passionate question that many would ask, and blow it open before we even get started. Kill the reviewer, well, metaphorically.

Alan,

Thanks for your comment. We wouldn’t give away a plot. This is history, not a mystery.

Ed.