Traction Forward!

By Philippe H. Defechereux

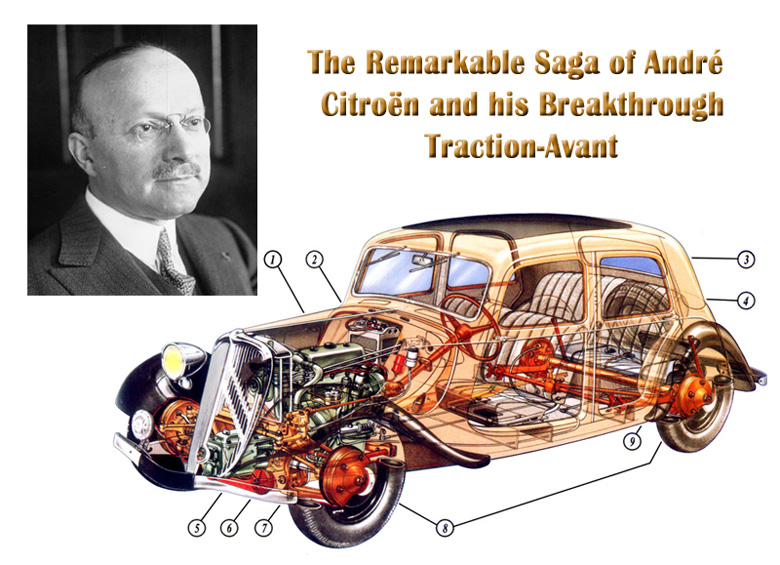

The year 1934 was to be André Citroën’s finest yet, the highest summit in a vast range of accomplishments already marked by several impressive peaks in his two preceding decades. And the year 1934 did start well for great French industrialist. After turning 56 on February 5, in mid-April he witnessed his life’s two grandest industrial creations come to life together, for they were entwined from conception: His new and thoroughly revolutionary Traction-Avant sedan began to come out fully formed and by the hundreds daily. This from his just-completed car production plant in Paris by the Seine, then by far the biggest, most modern and integrated mass-production automobile facility in Europe.

The company’s 300 dealers and agents, who a month earlier had been treated to a formal “Banquet Preview” of the new Citroën 7, as the car was first officially called based on the complex French fiscal horsepower rating, were filled with of enthusiasm. Immediately, they started selling the new low-slung wonder en-masse, in spite of serious early mechanical problems popping up in many spots on the new vehicle, due to the rushed concept-to-production schedule. But the basic design would prove flawless. Most defects were corrected before year-end, while the early buyers were financially protected, as Citroën had also pioneered a full customer guarantee policy.

The 1934 Citroën “7C”, best of the three new standard versions (A, B and C) of that first year. In-line four-cylinder 1,628cc ohv engine delivering 36 HP. [There was also the “Model 7S” in 1934.] Photo by Brandes Elitch

Dreadful Economic Winds

Unfortunately, 1934 was not a good time to have flown too close to the sun in Europe. In the middle of that year, France, like the United States and much of Europe, was still mired in the endless aftershocks of the global 1929 economic crash triggered in Wall Street. The French political system had become consistently volatile – 16 different PMs of diverse parties between late October 1929 and October 1934, or more than three new PMs per year, had succeeded one-another. Unemployment was still high and money was tight. Car sales were deeply affected. Peugeot unit sales for example, dropped by 40% between 1930 and 1932 alone.

As a result of this economic morass and his gigantic financial bet, André Citroën did not get to enjoy this fast and promising take-off for very long. Always more of a great visionary than a good accountant, he had bet and borrowed too much, too quickly, to bring his grand plan beyond birth on safe financial footing. By the middle of May, 1934, the Banque de France – France’s Central Bank -published a report indicating that Société Citroën now faced losses amounting to 200 million Francs (roughly $450 million in 2015 US dollars!).

The Citroën 7C version did not change much between 1934 and 1939. The cheapest of the growing model range, it became the staple and most seen “Traction-Avant” in Europe. It was also built in England (Slough), Belgium (Forest), Germany (Cologne) and even Denmark (Copenhagen). That in itself is remarkable for a pre WW II car. Photo by Roy Smith.

That official news almost immediately stopped all further credits to the already-heavily leveraged company. André Citroën had been his own man since early adulthood, with several ambitious initiatives having led to successful, often impressive results. In fact, he became an “Industrial Hero” during World War I, which earned him the highest civilian medals France could offer (see sidebar, below). Though André Citroën immediately threw himself full-power into the fray to save his company, seeking new creditors in endless meetings, even exploring talks with Henry Ford’s French representative, Maurice Dollfuss; it was all to no avail. The French government, itself weak, would not provide credit guarantees. In the early days of December, Citroën suddenly confronted formal overnight legal bankruptcy.

The “Quai de Javel” plant’s façade, facing the Seine River. Even when the factory was vastly enlarged in 1933, the historical façade was kept unchanged. Finally demolished in 1984, the vast space occupied by the famous plant was wisely turned into a splendid city park by the Seine, and officially named “Parc André Citroën.” Citroën Communications photo.

Saved by Michelin

As Fate would have it, a new man had just appeared onto the stage in Paris on November 8, exactly a month before André Citroën’s deadline. That was the day when the French Parliament had agreed to endorse Pierre-Étienne Flandin as the the 17th French PM since the 1929 crash. The new Government’s leader, soon enough frightened by the prospect of further massive job losses sure to follow a Citroën plant closing, took little time to find a solution, one that in the end would prove excellent for his country’s car industry. PM Flandin helped convince Citroën’s biggest creditor, Michelin & Cie, to take over ownership of Société Citroën as part of the car company’s bankruptcy agreement.

Founded in 1889 by brothers Edouard and André Michelin, the tire company from Clermont-Ferrand was financially solid in 1934. Fewer cars were being sold, but tires still wore out. They certainly were familiar with the car industry and Citroën. And so they agreed if their conditions were met. Pierre Michelin, son of Edouard, would take over as co-president of Société Citroën, with Citroën carrying the same title. This, however, would only be after the Citroën founder had handed over the 60 percent of his shares to Michelin & Cie, thus losing control of his cherished industrial creation.

And so it proceeded. But still André Citroën had reasons for hope. When a full production count of the new model was completed in mid-January, 1935, almost 20,000 Citroën 7s had been manufactured and were in the hands of customers or dealers, a mere nine months after production start. And within that same time span, two sets of significant technical improvements/enhancements (7B and 7C) had also been fully integrated into the production models, solving all the early defects to a large extent.

If the 20,000-unit count is annualized, that would represent a yearly output rate of over 27,000 Model 7s, even discounting the inherent slow start of a revolutionary model in an entirely new plant. Meanwhile, production of the Traction-Avant’s predecessor, the Citroën Rosalie, now equipped with the more modern Model 7’s ohv engine, had continued at healthy levels of over 100/day. Henry Ford used to close his highly efficient plants for months at a time when a model change-over was taking place.

A Fatal Blow

Though this forced take-over of Société Citroën was a smart move for France, it proved a crushing blow for its creator. Even those very hopeful signs would not be enough of a salve for the great Parisian pioneer and industrialist. On February 18, 1935, the heretofore hyper-energetic visionary engineer and carmaker fell ill and had to be hospitalized. Within a few weeks, stomach cancer was diagnosed. Despite an operation in May, André Citroën died on July 3, 1935, at age 57.

He left behind his grieving wife Georgina and the three children they had raised together; but also a breakthrough new car and production facility that would change the industry in profound technological and historical ways.

A few days after the passing of Le Patron, Pierre Michelin was named sole president of Société Citroën. An era had passed, but the name still lives brightly throughout Europe to this day.

A Revolutionary Legacy

Had the masterful French industrialist lived a normal lifetime for his era, say to age 75, he would likely have become the single greatest engineer/car manufacturer in European history.

How revolutionary was the Citroën Traction-Avant? Let us start with a quote from a remarkable book: “Car of the Century – The 100 Candidates” (Amsterdam BV, 1998), to which 135 veteran automotive journalists from 52 countries and five continents contributed significantly:

“The model …was a car that broke new grounds in almost every aspect of its design. Its forward-looking styling set a pattern of individual, timeless design that was to be a Citroën specialty for five decades. … In almost every aspect of its design, the Traction-Avant was years ahead of its time. …The Traction-Avant was one of the greatest success stories in the history of the automobile.”

The Citroën 7S (“S” for Sport) was also launched in 1934. It was powered by a 1,911 cc version (46 HP) of the model 7 engine, the largest yet. This attractive two-door Coupé is a 1937 production. Wiki Commons image by Lars-Göran Lindgren Sweden

As we shall see, the Traction-Avant was also an eminently adaptable car, and it was manufactured in countless versions over its 22-year lifetime, up to a grand total of a fraction below 760,000 units. It was also actively deployed in wars – by bad guys and good guys alike, featured in countless movies and even used effectively by an infamous Parisian posse of killer-gangsters for its fast getaways.

Before we count the ways Citroën and his team brought together a dozen innovative technologies in perfect harmony into a revolutionary new model, we need to give credit to the other brilliant minds who indelibly contributed to the final result.

The Great Andrè Lefèbvre

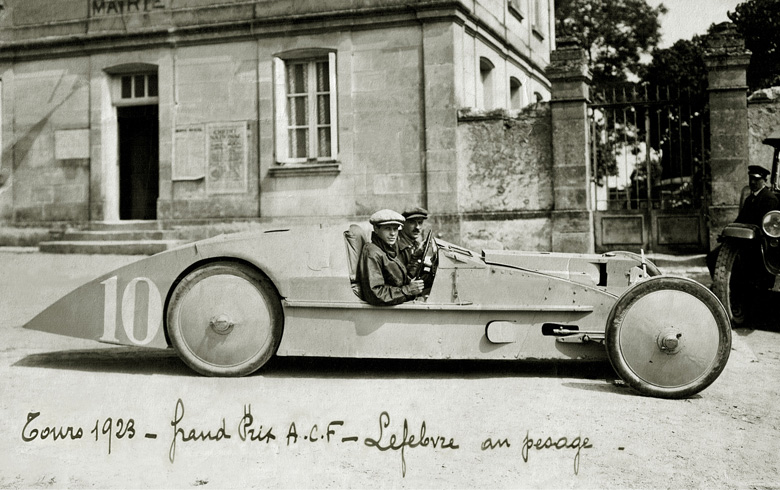

The 1923 C6 “Laboratoire” racer, designed by André Lefèbvre (here at the wheel) by request of Gabriel Voisin. The latter asked his brilliant engineer to compensate for its low-performance engine – still using sleeve valves – by creating a very light racing car with emphasis on refined aerodynamics. This sleek racer, the first featuring an aluminum unibody, unfortunately did not perform well in the 1923 French Grand Prix due to its poor power output. This led Voisin to abandon racing, leaving the later Silver Arrows without any seriously innovative French competition. Courtesy Sporting Magazine.

First was Andrè Lefèbvre (see Pete’s book review of July 7, 2010). Born in 1894, his early passions were mathematics and engineering, particularly as applied to that latest magical invention: flying machines. During World War I, in 1916, he had already gained a bright enough reputation to be hired by Gabriel Voisin, a famous aviation pioneer whose company was now building bomber aircrafts for France. Once the global conflict had ended, horrified by the human wreckage wrought by war machines, Voisin switched to making high-end automobiles in 1919, under the brand name Avions Voisin.

1934 Voisin C27 Aerodyne two-door Coupé. The Coupé has a wheelbase of 122”, shorter than the C25 sedan of the same year by 7”. The 1934 Aerodyne is one of the most desirable of Voisin’s cars. Photo by Hugues Vanhoolandt.

Lefèbvre went along and perchance found himself absorbing with fervor the most modern techniques applicable to small-series automobiles from Gabriel Voisin and his chief designer, André Noel. All Voisin automobiles (1919-1939) were exceptionally well-designed, remarkably advanced and fully idiosyncratic. Avions Voisin pioneered or emphasized lightness and the use of light metals, especially aluminum; unibody chassis construction, central weight distribution and low-slung suspension. All tagged with a price only the wealthy could afford.

André Citroën must have been an attentive admirer of his high-end colleague’s entire design philosophy. And likely intent on applying all he could to his planned revolutionary mass-production new model. So when the French economy went south in 1931, luxury cars stopped selling; Gabriel Voisin was forced to dismiss many people, including Lefèbvre, who soon was hired by Louis Renault. The two men never did see eye to eye in the least. Early in 1933, André Citroën was only too pleased to offer the 39-year-old star engineer the job of chief designer for his “Model 7 Traction-Avant.” Citroën’s bright new recruit would have excellent help, le Patron having previously hired the young but already recognized body designer Flaminio Bertoni – then 30 and having left Italy for France only two years earlier.

Polishing the Precious Stone

Michelin & Cie indeed inherited a jewel of, well, massive proportion. To their credit, the owners of the famed tire company did a superb job at taking their “diamond-in-the-rough” and turning it into the brilliant piece of automotive jewelry that the new car, soon to be re-named “Traction-Avant” by popular acclaim, would become.

Their first steps were to successfully insure that Lefèbvre would stay with the company, then to bring in a highly competent and entrepreneurial leader by the name of Pierre-Jules Boulanger. That man and his team would nurse the new Citroën to full maturity before the German Blitzkrieg attack on France in May, 1940. After the war, still along with Lefèbvre and Flaminio Bertoni, the team would further evolve the Traction-Avant, then help bring about new breakthrough models for Citroën especially the 2CV and Traction-Avant’s successor, the incredible DS.

The unimaginably harmonious integration of a dozen technical advances into a single new model meant for mass production will be detailed and illustrated in our next article. So will its crowning version launched in 1938, the Citroën “15-6,” with widened and lengthened body and powered by a new 2.6 liter six-cylinder. It would justifiably be named “Queen of the Road.”

Sidebar: Citroën, World War I Hero

André Citroën’s most remarkable contribution prior to becoming a car manufacturer in 1919 had been made on behalf of his country during World War I. After the sudden declaration of war by Germany on August 4, 1914, the French army soon found itself barely capable of containing the massive German onslaught towards Paris. By October, it also discovered its gunners were desperately low on shells, especially of critical heavy artillery shells. The dated French manufacturing rates were just inadequate for the “industrial war” it now confronted.

André Citroën, mobilized in August and serving on the front as Captain of an artillery regiment, observed this shortage first-hand and with despair. But the former Parisian socialite had always been a man of initiative and was no stranger to mass-production engineering.

As early as 1912, then in charge of turning around the struggling Automobile Mors company based in Paris, he had taken it upon himself to travel to America and visit the Ford Highland Park plant in Dearborn, at the time the only mass-production facility for any heavy, complex product in the world. There, André Citroën studied “Fordism” and came back to France a passionate convert.

So in December, 1914, as he watched his own gunners daily running short of shells against the onrushing enemy, Citroën quickly decided to contact the French War Ministry, with a plan. He proposed to Louis Baquet, the General in charge of France’s artillery, to let him design and build a modern factory in Paris that would increase shell production rates significantly. Out of sheer despair, General Baquet gave him near-instant approval. Wasting no time, the French “Fordist,” in just three months, financed and directed the building of a 40-acres, ultra-modern munition factory, sited next to the Mors plant at “Quai de Javel” by the Seine River.

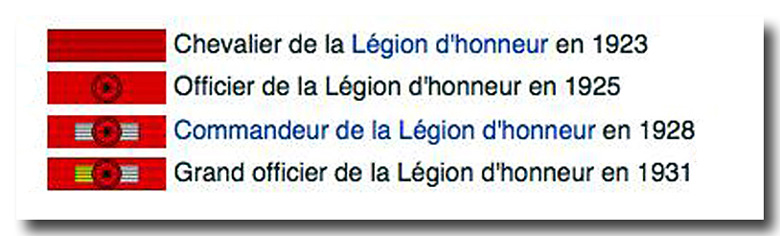

Before the end of 1915, his new factory was producing 10,000 heavy Type 75 shells per day, a phenomenal rate for the era. It may have helped save France from defeat. Based on that and many other accomplishments –he invented the food ration card system- that deployed high-productivity engineering and other ambitious rationalizations for his country during the war, Citroën was awarded his first Légion d’Honneur in 1923, France’s highest official recognition for civilian achievements. By 1931, he would receive his fourth and the highest: Grand Officier.

Chevrons Gears, Famous Logo

Every part of André Citroën’s life story is full of fascinating details. The origin of the famous “Double Chevron” logo is a perfect example.

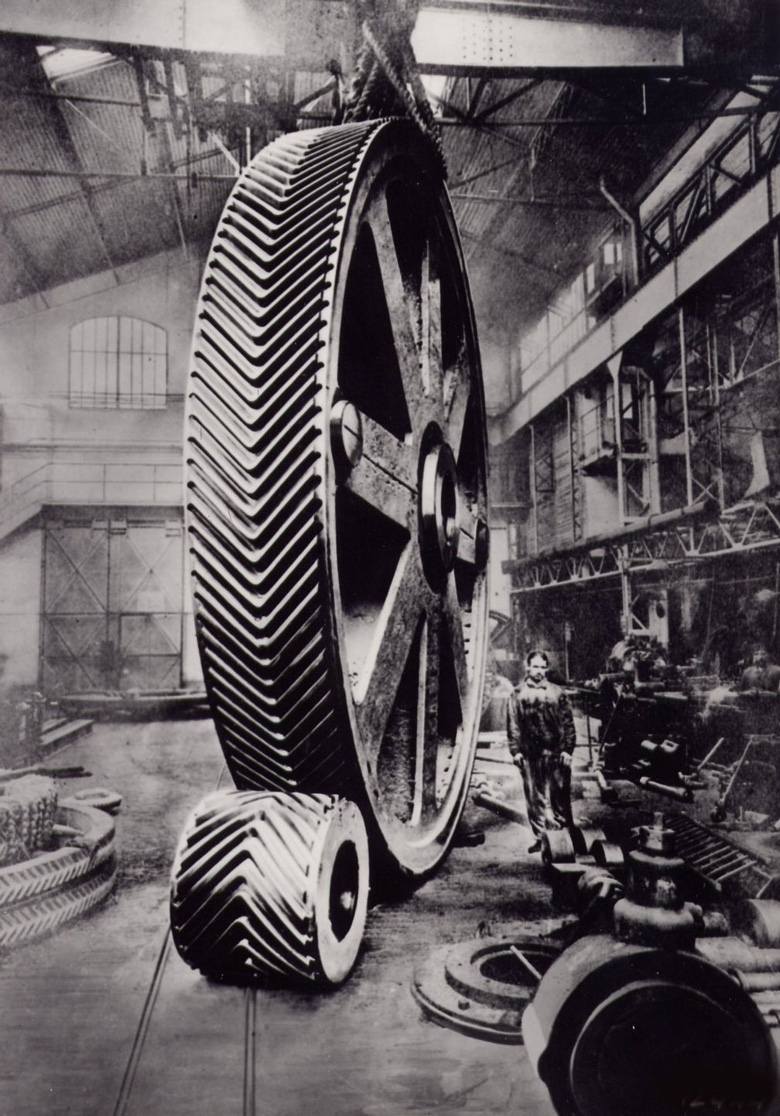

In the year 1900, at the age of 23, André Citroën took an Easter vacation trip to Poland, his ancestors’ country of origin. There, a distant family member introduced him to a customer of his, one who specialized in manufacturing small but cleverly engineered wooden reduction gears for use in the production of woven threads for the textile industry. Their V-shaped helicoid teeth offered two major advantages over straight-teeth gears: first, the large, smooth chevron-angled contact surfaces of two engaged gears allowed for much reduced torsional stress on the gears’ axles, allowing for for much larger reduction ratios. Second, the chevron gears were almost completely noiseless during operation, a great advantage in large factories with hundreds of employees and countless gears in operation under one roof – if one day they were made of metal and much bigger.

André Citroën, already a graduate of Paris’ Polytechnique School, immediately saw the potential for heavy industry. The latter was fast switching from steam power to electric motors to drive machinery. The much faster rotation speed of electric motors required large reduction ratios to power machinery. On the spot in Poland, he bought the patent, for future use. No company in Europe had the machines to produce such fine gearing in metal. But one day, who knows?

It was during his trip to America in 1912, on behalf of Automobile Mors, that André Citroën finally saw the advanced industrial machine tools capable of the strength and high precision to cut his chevron gears through steel billets, the way he knew was inevitably required. With the help of his banker, plus his schoolmate Paul Hinstin, the “Citroën, Hinstin & Cie” company was founded in Paris shortly after his return from Dearborn, and American machinery was purchased. Once the gears were manufactured in Paris, many patents were obtained for diverse uses, and the business grew fast. This caused his early partners, having their own business to care for, to sell him their shares. Soon, André Citroën moved the production facility near the Mors factory and the “Quai de Javel,” renaming it “Société Anomyme des Engrenages Citroën” (“Citroën Gearing Company”).

Sure enough, our hero chose the “chevron design” for his company’s logo. Within four years, the company had become exceptionally successful, laying the basis for the Citroën’s fortune. Then World War I intervened, and you already know André Citroën’s role in that conflict.

Congratulations;

A great review, Andre Citroen was one of the greatest manufacturers in the motor industry. Embracing the latest technology of the time, introducing mass production-street years ahead of other European Manufacturers!

And to consider the Traction was marketed into the 1950’s and draw your attention to the fact Andre Citroen by the end of the 1920’s was the fourth largest auto manufacturer in the world after GM Ford & Chrysler.

What an achievement!

Excellent history and a brilliant engineer. I wish DKW also received as much admiring attention for their front wheel drive small two stroke cars which were also produced from early thirties.

I Love this article and as a devoted fan of Citroen cars I’m delighted to know the history behind the company and to meet Andre Citroen, what a fascinating person.

I am old enough to remember Tractions Avant in Spain in the late 1960s, when my father bought a DS23 wagon that we took home to the States. Thank you for a marvelous piece that revived my happy memories of the glorious Citroens of my adolescence. If only they had a bit more power…

Excellent!

The US contribution to the engineering of the T has a hard time taking hold. Citroën cooperated very closely with Budd in Phikadelphia. There is no doubt that the basic layout of the TA came from the work done by Joseph Ledwinka, the chief engineer at Budd. See my article in Citroenvie on this subject.