This article originally appeared in VeloceToday on February 29, 2012

Story and Photos by Karl Ludvigsen

Journalist Gordon Wilkins said that ‘although it has an impressive performance, it produces in the driver the uneasy exhilaration which may be got from shampooing a lion.’ Consumer advocate Ralph Nader called it the only car that was more dangerous than the much — oft unjustly — maligned Corvair. The German Army was said to have barred its officers from driving it, lest their numbers be diminished even more rapidly than World War II was already managing.

How are we to judge these harsh estimations of the Type 87 Tatra? I found a good assessment to be 14 years of ownership of just such a car. Why did I buy a Tatra T87 from the Honda dealer to whom it had been traded for two motorcycles? I had always nursed a passion for the innovative experiments of the 1930s with streamlined rear-engined cars. Burney, Stout, Tjaarda, Porsche, Fuller, Bel Geddes, Ledwinka, Übelacker and Schjolin were only the best-known of the many adventurous designers and engineers who saw the future of the automobile in rear engines and advanced aerodynamics.

In the 1930s most of these men designed and built, at best, short series of cars or prototypes. Hans Ledwinka was the only engineer whose advanced rear-engined passenger cars were series-produced during the decade. The pathbreaking Tatra cars were manufactured by Ringhoffer-Tatra at its sprawling factory at Koprivnice in Moravia, since World War I part of Czechoslovakia.

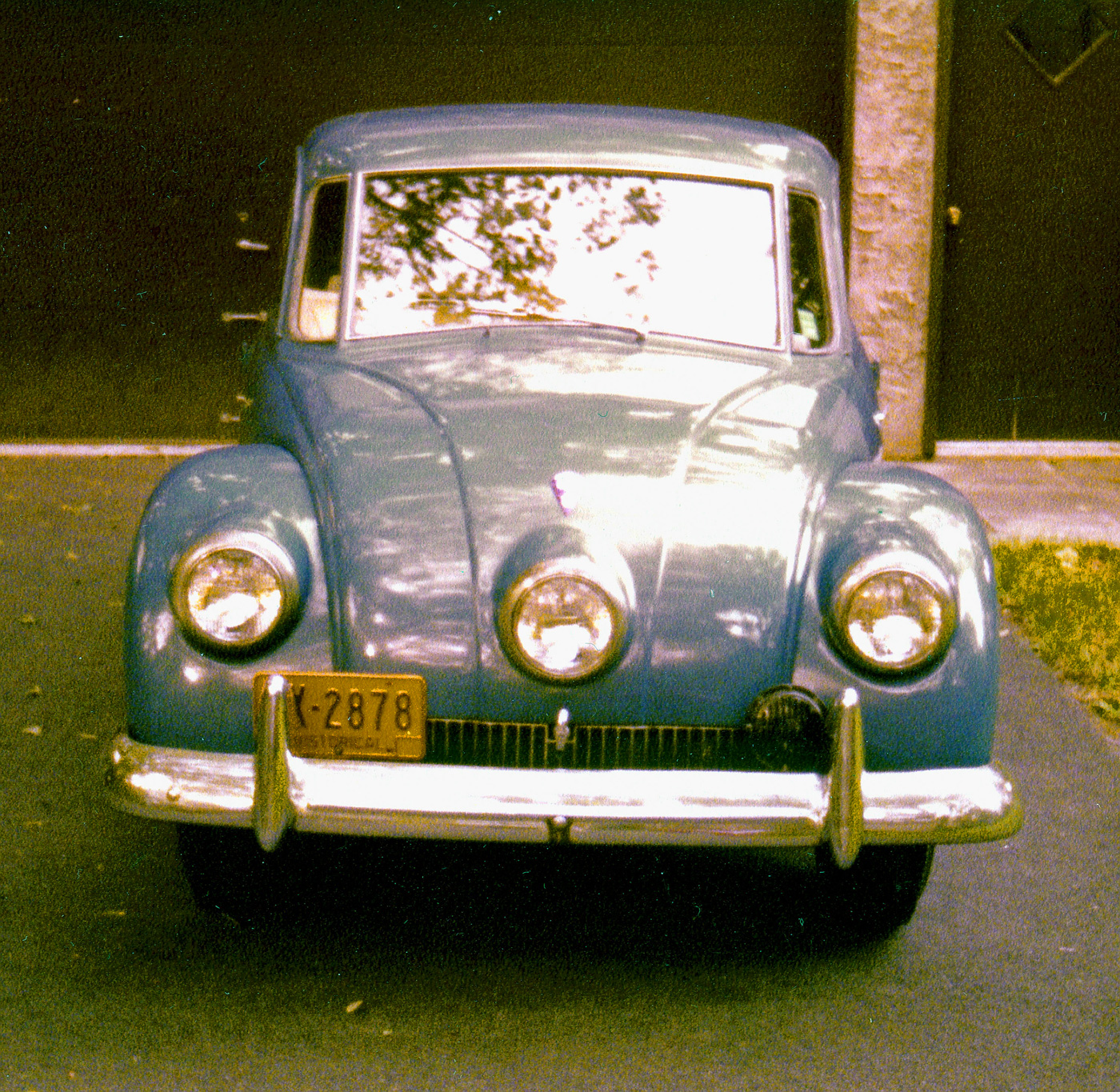

The Ludvigsen Tatra as photographed in 1964. Rear vision was better than reported. The car was very original aside from the bumpers, which are a bit larger than the stock items.

Tatra stunned the motor-engineering world when the streamlined, rear- engined Type 77 was introduced to the press on 5 March 1934. (see last week’s history article) Tatra had built smaller rear-engined prototypes in 1931 and 1933. But this was a big car seating six, powered by an air-cooled V-8 overhung behind the rear axle. And it was spectacularly streamlined.

Austrian engineer Erich Übelacker worked under Ledwinka to create the astonishingly aerodynamic forms of the T77 and its successor the T87 (He had a hankering for sevens.). Before he left to join Steyr in 1936, Übelacker completed the upgrading of the first model to the T77a and the design and initial proving of the T87.

A smaller sister model, the 1,749 cc Type 97, was short-lived. This was not because it was faulty; Gordon Wilkins found that ‘it will corner at speeds which produce pop-eyed awe in passengers whose standards of roadholding are based on experience with cheap small saloons.’ Tatraphiles maintain that the T97’s flat-four air-cooled engine at the rear caused its termination by the Germans, who supposedly thought it too much akin to their forthcoming Volkswagen. In fact it was one of many victims of the culling of small-volume models by the Reich, in the name of efficiency, just before the war by car-industry czar Colonel von Schell.

The T87, on the other hand, was enthusiastically welcomed by the German high command. This was a big, fast, comfortable courier that seemed tailor-made for the four-lane Autobahns that Fritz Todt’s engineers were building throughout the Greater Reich. Todt himself owned and was driven in one, according to Tatra historians Ivan Margolius and John G. Henry. It was one of the more expensive cars of the day, selling in Germany for RM8,450. A 2½-liter 6-cylinder Opel Kapitän was less than half as costly at RM3,975.

Shorter and lighter than the cumbersome T77, the T87 was the first Tatra to combine air cooling with a chain-driven single overhead camshaft for each cylinder bank, opening vee-inclined valves through rocker arms. Each aluminum cylinder head was individually cast. Built like a light-aircraft engine, it looked like one when the big louvered rear deck was unlocked and lifted. From its 3.0 liters it developed 74 bhp at 3,500 rpm.

The looks are as startling now as they were in mid 1930s. But the lines were good; in 1978 a Tatra T87 was aerodynamically wind tunnel tested and found to have an amazing Cd of only 0.36.

Modest though this power may seem, its V-8 was capable of speeding the T87 to 96 mph with standard tires and 103 mph with special high-speed tires. This was because the T87 not only looked aerodynamic, it was aerodynamic. A measurement of a drag coefficient of 0.24 made contemporaneously on a one-fifth-scale model seemed too low to be true and indeed was. When an actual T87 (Hans Ledwinka’s personal car) was tested in the big Volkswagen wind tunnel in 1979 it was found to have a coefficient of drag (Cd) of 0.36, still a stunningly low figure for the years in which it was built. Most cars then had a Cd well over 0.50.

Tatra’s operations were integrated into those of the Third Reich’s wartime vehicle sector; the rugged and fast T87 was seen as a useful addition to its military capability. Among other applications the Luftwaffe was assigned one as an experimental vehicle. . Felix Wankel, consulting with the Luftwaffe on rotary-valve systems, was proud to be driven in a T87 during the war. A military police unit that served in Italy and Yugoslavia maintained a fleet of T87s.

After WWII, one car was obtained from Germany by the British Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders and assigned to Vauxhall for evaluation. Another T87 in British hands was the pampered transport of Major Ivan Hirst, the officer then in charge of the Volkswagen factory at Wolfsburg in the British zone of occupation. Found abandoned near the works in nearly-new condition, it was refurbished by VW staff and reserved for Hirst’s exclusive use.

Production of the T87 continued through the war, without interruption, to 1950. Mechanically the post-war T87s differ little from their predecessors. A late-1940s facelift blurred the architectonic purity of the original by submerging the headlamps into the wings. In all, output of the T87 came to 3,056 units.

Owning a T87

My Type 87, made in 1947, was externally indistinguishable from the original of a decade earlier, apart from some ex post facto bumpers. It was said to have been resident in the United States for many years after being imported by the novelist John Steinbeck. Owned by a motorcycle enthusiast who had no difficulty coping with an engine overhaul, it had clearly been driven far and fast.

Among other bits and pieces I was missing the elbow that joined the carburetor to the cylindrical air cleaner. Thanks to the intervention of auto-publishing pioneer Floyd Clymer, I was kindly sent one by Motokov in Prague. A simple rotation of a sleeve inside the cylinder changed the source of the engine’s inlet air from the fresh-air ducting to the warm-air exhaust for winter operation.

Missing in this engine photo is the cylindrical air cleaner which Ludvigsen was able to find through a contact in Prague. Note the ducting for air cooling.

Maintenance access to the massive transaxle was obtained by sliding out the floor of the (quite roomy) luggage compartment behind the rear seat. It needed frequent checking because an oil leak from the gaiters enclosing the swing-axle pivots was difficult to fix. When I visited L. Scott Bailey, publisher of Automobile Quarterly, I took along my own oil pan to avoid soiling his handsome gravel drive.

Other servicing needs were easily met — with some ingenuity. A two-stroke Saab silencer proved adaptable as a replacement. Leaks from the oil cooler mounted at the front of the chassis needed attention. A tired mechanical fuel pump was aided by an electric pump. The central chassis-lubrication system, worked by a press of a foot plunger, worked well.

Piloting the T87 produces a concatenation of impressions. Contrary to popular opinion there is some vision through the rear louvers — though an outside mirror is essential. Its rack-and-pinion steering is sublime — light, direct, precise as a fine machine tool. Yet its shift is redolent of an earlier era with a long, deliberate travel, distinctly notchy gate and absence of constant-mesh gearing in first and reverse.

The T87’s performance is impressive. First and second gears are relatively short, well suited to hilly terrain. Sixty miles per hour is easily exceeded in third, however. The big Tatra cruises comfortably at any reasonable highway speed. And its top-speed claim was reinforced by the timing of a rebuilt T87 at a two-way average of 102 mph in Australia. The same car (faster than standard?) accelerated from rest to 50 mph in only 10 seconds, much quicker than the 18 seconds recorded during Vauxhall’s test of a war-weary vehicle.

With the V-8’s friendly rumble well to the rear, facing the fully equipped dash and viewing the world through the three-part windscreen, driving a Type 87 is an unique experience — not to mention the gobsmacked expressions on the faces of other motorists. As my friend Luigi Chinetti, Jr. said during a turn at the wheel, ‘It’s like a cross between a Greyhound bus and a P-51 Mustang with holes in the right wing!’

Suicide doors, three lights, a three piece windshield and a rear engine set the Tatra apart from just about everything else on the road and elicits many comments from other motorists.

Handling? Damped in rebound only, and firmly, the T87 copes brilliantly with a wide range of surfaces. Wet roads want watching but with sensible driving the Tatra is a pleasure to handle. And I experienced it at its worst: a rear-tire blowout at speed on the Connecticut Thruway! Substantial yaw angles were reached but, thanks to the T87’s high polar moment of inertia and quick steering, I managed to gather it up and come safely to rest.

So, I have shampooed the lion and lived to tell of it. I can well imagine that during the war the high performance and quietness at speed of the T87 may have lulled some German officers–more used to a DKW or Opel Olympia–into situations from which they could not extricate the Tatra. Indeed, the opening page of the German-language owner’s manual of May 1943 offers this prominent and specific warning:

With the Type 87, the Ringhoffer-Tatra-Werke A.G. is placing a car in your hands that can reach a speed of 150-160 km/h. Not so many years ago this was a record speed for automobiles and in normal highway motoring for a touring car — for the non-professional driver — it is a very remarkable performance. Riding in the streamlined rear-engined Tatra is so secure and graceful, and thanks to its wind-cheating shape so smooth and quiet, that only a glance at the speedometer will show that you are travelling much faster than you thought. So even with the exceptional roadholding and first-class braking, don’t forget to be constantly cognizant that you are driving a very fast car whose braking distance at 160 km/h is two and a half times as long as at 100 km/h.

Therefore drive carefully and with the greatest alertness at all times!

This was a salutary admonition. But were the German military actually discouraged from driving these cars? I look forward to seeing the documentary proof. Until then I must consider this a canard.

Under the hood are two spare tires. Luggage space was to be found between the rear seat and the engine compartment.

Certainly the Vauxhall engineers were wary of the T87’s handling, calling it ‘vicious oversteer’ and eschewing a top-speed test for fear of ‘the Tatra’s dangerous lack of stability.’ They found that it steered neutrally up to about 0.3 lateral g and then required counter-steering. Over much of its cornering range it handled with predictable ease and precision. Indeed, Vauxhall went to extra trouble to ascertain just why its steering felt so responsive. The absolute cornering limit was kept low by the poor quality of the tire compounds of the day.

Vauxhall was impressed by many aspects of the T87. ‘The designers of this unorthodox car,’ its engineers reported, ‘have produced a vehicle that is full of interest, having several very good features.’ Its quietness, low aerodynamic drag, performance, absence of roll in cornering, excellent forward vision and roominess were praised. So too was its consistency of weight distribution between the empty and fully laden conditions.

What of ‘the designers of this unorthodox car’? The engineer who had piloted Tatra down its unique road was interned after the war by the Czech authorities, ‘who were following instructions issued to them by the Soviets,’ said Margolius and Henry. 1 Although still an Austrian citizen, Hans Ledwinka was convicted by the Czechs of collaboration with the Nazis and sentenced harshly to six years’ imprisonment.

Not surprisingly, when Ledwinka was released in 1951 he turned down an invitation to return to Tatra. Instead he settled in Munich, where he maintained his interest in advanced vehicle engineering until his death in 1967.

‘After his release he received a number of rewards and distinctions,’ wrote his second son and fellow engineer Erich Ledwinka, ‘but a rehabilitation from the Czechoslovak government never came.’ In the Type 87 is, at least, ample recognition of Hans Ledwinka’s admirable intolerance of the orthodox.

Footnotes

1. Ivan Margolius’s and J. G. Henry’s book “Tatra – The Legacy of Hans Ledwinka”. SAF Publishing, Harrow 1990

Absolutely wonderful. Great insights into a very unique and interesting car. Thank you for posting.

FWIW, Ledwinka had a brother in America working for the Budd Co., of unit body fame.

Hi all

I am a CITROËN fan who drives five thousand kilometres yearly in a Traction 15/6H but in my imaginary garage I really would like to owne and above all drive a Tatra.

Thank you for your article that reduced once again my ignorance.

Best regards

Richard Boudrias, Montreal Canada

I think Preston Tucker used many of features the Tatra 87 in designing the Tucker.

The Tatra was one fascinating vehicle. I was always fascinated with the several I ever saw. Thanks for injecting Tucker as there are so many similarities. Neighbor of mine worked for Bliss and set up the body presses for Tucker. The Czecks were and are very clever engineers. The first Skodas were built to drive like a truck, but strong I guess. They didn’t sell too well here in the USA< but the European Skodas are good ones today.

As I understand it, Volkswagen “purloined” Tatra designs for the Beetle and many years later had to pay retribution.

I was in Prague in 2012 and saw one behind a Porsche garage next to our hotel. I sneaked into their parking lot and took photos including under the bonnet/hood before curious mechanics came out to see what my interest was.

Fortunately, due to to incompatible language issues, nothing came of my transgression.

Vey impressionable car in photos, but even more so in the flesh. Black of course.