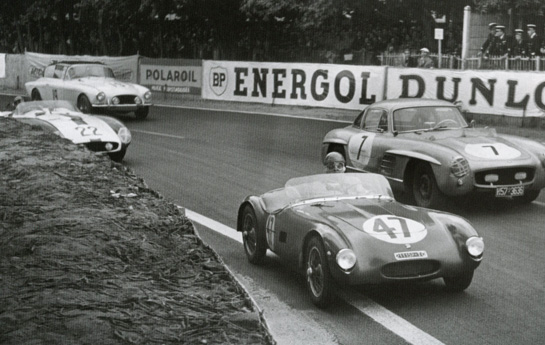

The Damonte OSCA Vignale coupe at Le Mans in 1953. From the book 'Le Mans The Official History of the World’s Greatest Motor Race 1949-1959'

.

Le Mans The Official History of the World’s Greatest Motor Race 1949-1959

Haynes Publishing, U.K. 2011 ISBN 978 1 84425 537 5

352 pages $69.95

Illustrations: 50+ color & 300 b/w ill

Size: 9.0 x 11.0 x 1.0

Weight: 4.063 lb.

Licensed by the Automobile Club de l’Quest (ACO)

By Quentin Spurring

Order from Qbookshop

Review by Pete Vack

All photos courtesy Haynes Publishing

Author Quentin Spurring believes that the first post war decade at L e Mans was significant because the race survived after not one but two tragedies, the first being World War II; the second ten years later after the 1955 accident which killed over 80 spectators. The tragedy shut down racing temporarily and forever in some countries (if you have even wondered why there in no F1 race in Switzerland, the Le Mans disaster is the reason). Of course he is correct; racing did not resume at the Sarthe circuit until 1949 but quickly regained its international status and reputation. After the disastrous 1955 event came the 1956 event, never missing a beat demonstrating how important the event was to French prestige and the auto industry in general. Le Mans, after all, even then was one of two events (Indy being the other) that registered with the media and John Doe in general.

But for us, that decade was of interest because never since and never before did the Le Mans start feature so many different makes and models of cars. Le Mans, at the time, was a great but potentially dangerous mixture of the odd, bizarre, the tiny and the experimental that shared the narrow track with the huge, strapping fendered-Grand Prix cars of the prewar era together along with the most advanced new cars of the era. They were truly interesting fields and unlike later years, where certain makes won victory after victory, in ten years the event went to Jaguar five times, Ferrari twice, Talbot and Mercedes and Aston Martin, one each.

But for us, that decade was of interest because never since and never before did the Le Mans start feature so many different makes and models of cars. Le Mans, at the time, was a great but potentially dangerous mixture of the odd, bizarre, the tiny and the experimental that shared the narrow track with the huge, strapping fendered-Grand Prix cars of the prewar era together along with the most advanced new cars of the era. They were truly interesting fields and unlike later years, where certain makes won victory after victory, in ten years the event went to Jaguar five times, Ferrari twice, Talbot and Mercedes and Aston Martin, one each.

The fifties also saw a larger percentage of makes entered. The high year was 1950, when 28 different makes—not models– were on the grid. That number gradually dwindled as the overall entry list which remained at about 65 cars was filled with the more prolific and successful cars such as the Porsche 550 series, the Lotus 11s, and Ferrari 250GTs.

1949: The Simca-Fiat engined Monopole which won the 1100cc class. It is followed by an HRG. Spurring provides a good bit of information on the French Monopole as well as other relatively obscure makes.

In the period from 1923 to 1939, 57 different manufacturers entered events at Le Mans; from 1949 to 1959, 64; and from 1960 to 1973, only 51 different makes ran the gauntlet at Le Mans.

Naturally, one might think that a book like Quentin Spurring’s latest effort “Le Mans 1949-1959” which only covers ten years, would be sure to cover all the angles, all the cars, and present all relevant stats. I hoped so, anyway, and decided to find out for sure. What I personally wanted to see was the images of all the cars, including photos of those poor oddsters left on the cutting room floor by tight fisted magazine editors, cars too small to mention, cars too bizarre to believe. These were cars largely ignored by even the motoring press. (As one famous car magazine editor once said to me, “We only want the Jags and Ferraris, forget that rare stuff.”)

1950: And here is that Czech Aero, aka Jawa. It won the 750 cc class in record time with two Dutch drivers who painted the car….orange.

Superficially, it looked a little light so I decided to do an actual count. Each chapter surveys a different year and each has between 30-35 images. Interestingly, there are no captions. The layout was done very well and the text closely accompanies the images, dispensing the need for separate captions. We wish that the words “above, left, right and below” were highlighted…searching for the sentence that describes the photo is made more difficult by the lack of bold faced font where caption information is indicated. But would I see photos of the VPs, the Ferry, the Callista, the Moretti 750GS, and that rare diesel, the Delettrez? Or how about those magnificent Bristol coupes? The Czech Aero Minor?

Well, yes and no. Lacking I complete photographic entry list (like the Indianapolis entries have), the authors and editors did a pretty good job of covering the field. Not 100 percent, but a good 85 percent of the cars entered are in some fashion recognizable in the accompanying photos. On the average, over half the cars on the entry list could also be found in photographs. Note that in one year there might be four almost identical Renault 4CVs entered;a photo of one is sufficient even for this reviewer.

1952: A class act. The Lancia B20 driven by Valenzano and Castiglioni won the 2 liter class and placed 6th overall. This is one of the real Aurelia factory comp coupes; note the low roofline.

So yes, most of the odd, ugly, small and ignored cars can be found in each year in addition to the standard Jag, Ferrari, Maserati photos. But not all. Some of the Gordini entries were not in photos; there could have been more of those Darth Vader Bristol coupes in 1954; better images of both Salmsons, Stanguellinis, etc. Yet on the whole this reviewer was please with both the photograph itself (many new images) and with the coverage.

So we give the photography a rating of 8 out of 10.

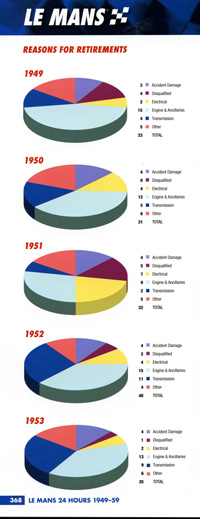

The organization of the statistics is very good, as are the stats themselves. Race information, entry list, marques on the grid, hourly results, class winners and index of Performance along with the Biennial Cup accompany each chapter. The Appendix includes yearly reasons for retirement, marque records, driver records, driver nationalities and pseudonyms, fastest practice and race laps, winning distance and average speeds, margins of victory, fastest cars in the speed trap. I can’t think of a statistic of any worth that does not appear. There is also a fairly complete Bibliography and an excellent index. 10 of 10 on stats and appendixes.

The organization of the statistics is very good, as are the stats themselves. Race information, entry list, marques on the grid, hourly results, class winners and index of Performance along with the Biennial Cup accompany each chapter. The Appendix includes yearly reasons for retirement, marque records, driver records, driver nationalities and pseudonyms, fastest practice and race laps, winning distance and average speeds, margins of victory, fastest cars in the speed trap. I can’t think of a statistic of any worth that does not appear. There is also a fairly complete Bibliography and an excellent index. 10 of 10 on stats and appendixes.

That leaves the text. Author Quentin Spurring has impressive credentials. He has been the editor of Competition Car, Autosport, Racecar Engineer, and reported on 26 Le Mans races. He is also the author of “Grand Prix! Rare Image of the First 100 Years” among other books.

Each year begins with a sidebar on organizational items, I.e. changes in the rules, modifications to the track, new classes. Spurring then describes the race in a page or two. He handles the 1955 accident with accuracy and good judgment.

Next, the best part. Along with matching photos, he provides a commentary on the teams and entrants. Generally beginning with the big bore cars and overall winners, he provides detail after detail about the cars, the drivers, the anecdotes, and the technical specs of many of the entrants. Thankfully he gives almost as much attention to the Callista as he does the Cunningham. The text sparkles with interesting comments and covers a great deal of ground. It is a joy to read and works as both entertainment and as a historical resource. His style is flowing, he handles a great deal of information with ease and there is much to learn from him.

1956: A nice (arnd rare) shot of the 750cc Moretti In 1955, Moretti entered two cars but were excluded as they did not meat the deadline. In 1956, two made the grid but both retired with engine problems. The coupe in the background is the Salmson with a Motto body. Great photo, informative text.

Perhaps because of the wide scope presented, occasionally Spurring spins out. Without looking for errors or incorrect minutiae, several bloopers popped up in the text. When describing the Cad Allard, he has it running a “SOHC Cadillac engine”. Off hand, we know Cadillac did not make a SOHC engine, but we had Brandes Elitch double check engineer Maurice Hendry’s comprehensive “Cadillac, The Standard of the World” (AQ 1983)…as well as all contemporary reports.. just to make sure we were correct. We found no reference in any publication of a SOHC Cadillac V8. A few more page away, we noted another error…the special Le Mans Crosley had generator (French Marchal, at that!) problems. For some reason Spurring calls a generator an alternator..twice. Again, we know offhand that alternators did not begin to replace generators until the 1960s, so we checked the AQ feature on this amazing purpose built Crosley and found the generator not alternator failed. Next, Spurring makes note the “chrome iron block” used by the fantastic Bristol 405 factory racecars in 1954-55. The term ‘chrome iron block’ is a sure red flag, and after a significant amount of investigation, we determined that the iron block BMW 328 engines as adopted by Bristol used dry piston liners, and more specifically cast from an iron chrome alloy by the name of Brevadium, which was used by Bristol in their aircraft engines. There is, of course, the possibility that for the 405 racing cars the entire block was actually cast using Brevadium, but we found no evidence for that pro or con. (our readers will surely let us know if we are wrong!)

1959: Wonderful color photo of the Cabianca/Scarlatti 196 Dino Ferrari. The development of this 2 liter car was the responsibility of Scuderia Automobilistica Castelotti. Cabianca retired after leading the Porsches.

We are not splitting hairs here or looking in earnest for errors. No one knows better than this Editor how mistakes creep into a text…we make our share of them in VeloceToday. But in almost all cases corrections are made immediately, a great advantage of having a text that can always be updated and corrected. Not so with the book industry though, and another reason why good editing and knowledgeable proofreaders are essential for both media, but even more critical with the printed text. Yet, in the publishing industry, there is less and less money to allot for the luxury of an editor and proofreader.

While the statistics, bibliography and index are all excellent, missing is any form of notation. Spurring writes some great stories, many of which can be logically attributed to the bibliography sources, but many not, and we yearn to find out how he learned so much and from where..and when.

Still we’ll give the text 8 out of 10 since overall, it is excellent and falls short of our usual expectations and demands of footnotes.

So where does that place this new effort from Haynes? It is part of a new series of books on Le Mans, each by decade and if the rest are as good as this one, buy each as they appear. Most certainly get this one…we’ll give it a 9 out of 10 overall and highly recommend it to anyone who needs either a good read or good reference. It is far superior than anything else that we have read on the subject.

Terrific report shall order a couple of books. Thank you for info that is orgional and worthwhile, not like most of the comic books on ferrari’s. TIDE ferrari france, last ferrari team to win class & finish in top 5 at LeMans. TIDE, 81 LeMans IMSA class winner, 512BBLM #31589. OWNED & RACED by tom I.davis sept 1980-july 1987. Sponsored by Jim Kimberly,Betty McMahon & Beatrice Cayzer Publications.