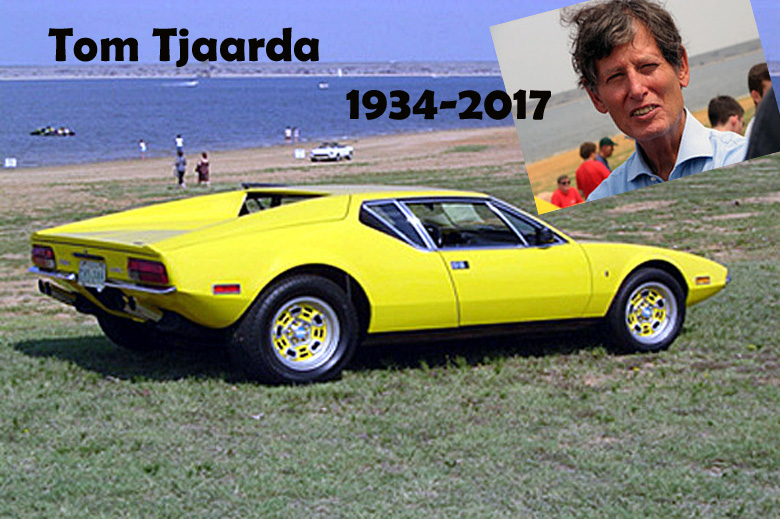

Tom Tjaarda, who needs no introduction to our readers, passed away last week at the age of 82. As well as a talented designer, he was always friendly approachable, kind and well liked. Below, we republish Professor Patricia Yongue’s article, “Tjaarda on Creativity”, from the January 5, 2016 edition of VeloceToday.

By Patricia Lee Yongue

“Creativity” is one of American auto manufacturers’ major deficits, asserted designer Tom Tjaarda, guest speaker at theItalianCarFest, Lake Grapevine, Texas, September 8-10, 2006.

In an after-dinner Q & A session, Tjaarda responded to audience lament over a current banality and imitativeness in American production car design. The attitude was hardly surprising, given that CarFest participants had just emerged from a full day of hot Texas sun and pure Italian style that momentarily occluded the view of Ferraris, Panteras, Lamborghinis, etc., as not exactly grocery store transportation. Still, Tjaarda made his point.

For Tjaarda, who is most certainly an artist, “creativity” means chiefly aesthetic creativity, not merely inventiveness or innovation. Creativity fuses style and beauty of form with function in unique ways. “We all know the words a Shakespearean actor is going to say,” Tjaarda proposed (with perhaps too much optimism), “but the power is in the actor’s delivery.” The intriguing, complex analogy by no means implies that Shakespeare’s words are not of themselves poetically powerful, or that cars are not mechanically powerful. Rather, as dramatic performance, both Shakespeare and automobile design flourish at the hand of truly artists. The potential for debate of this metaphysical, not to mention literary, issue is rich.

Wisely tabling metaphysics, Tjaarda singled out the Chrysler 300, with its Bentley-like elegance, as an exception to the American car with little delivery of design. He argued that the primary reason for Detroit’s general creative malaise lay not necessarily in a dearth of talented designers but in the physical and spiritual splintering of talent within the companies. In fact, he said, the diffusion of too many people in too many places simply defuses creative force.

A resident of Italy since his graduation from the University of Michigan in 1958, Tjaarda represents, of course, a generation of artists who worked in Europe for smaller organizations that, despite internal conflict and external rivalries, created some of the most admired body designs in automotive history. The Ferrari 330 GT 2+2 (Pininfarina), the Ferrari 365 GT California Spider (Pininfarina), and the de Tomaso Pantera (Ghia) are among Tjaarda’s own recognized accomplishments. He also presides over a small company, Tjaarda Design, in Turin, Italy. Still, he makes another point, if a sensitive one at the moment, given the recent dramatic downsizing at both GM and Ford.

“Harmony,” the focus of Tjaarda’s address and slide show at Grapevine, plays to the continuing dialogue about aesthetics and creativity in relation to performance and intended and/or realized function. Interestingly, Tjaarda included his father John Tjaarda’s Lincoln Zephyr (1934) in his historical inventory of autos emblematic of true harmony. Over the years, Tjaarda has consistently remarked on the rear-engined, semi-monocoque Zephyr’s final “evolution” into a “strikingly beautiful, well-proportioned, mechanically superior automobile” in spite of the bureaucratic “compromises” at Ford/Lincoln with which the project was fraught (Tjaarda, “I Remember My Father,” Special Interest Autos, April-May, 1972, p. 52). John Tjaarda’s indomitable resolve and talent, combined with his boss Edsel Ford’s own talent and acumen, urged the project into design-successful completion.*

With charming conviction, Tjaarda cited his rear (mid)-engined, monocoque de Tomaso Pantera to illustrate harmony. He infused power into the haunches of the Pantera, he said, with a rear upsweep line that inevitably draws the viewer’s attention. This design is logical as well as beautiful precisely because the car’s power plant is located in the rear. In a fine nuance, Tjaarda compared the design of the Pantera not merely to a panther, but to a panther at speed.

*A rear engined Zephyr? Well, yes. According to Wiki on John Tjaarda, “during the 1920s, he worked on a series of streamlined monocoque designs, known as the “Sterkenburg series”, before joining the Briggs Manufacturing Company as chief of body design. There he developed a concept car for the Ford Motor Company to be shown at the Century of Progress Exhibition (1933-1934) in Chicago. Known as the “Briggs Dream Car”, this was a streamlined rear-engined design, based on his previous work. Re-engineered as a front-engined car, this design was developed into the 1936 Lincoln-Zephyr.”

I was once briefly acquainted with Thompson Tjaarda. We both attended Birmingham High School in Birmingham, Michigan and while I was a year ahead of him we both shared a study hall, that time of the academic day when boys drew cars. Boy, did he ever draw cars. We did catch up a few years back when he was involved with a group that hoped to pick up the remains of the Shelby Series 1. Unfortunately the deal the deal got tied up in legal blather. But he did tell me a funny story about the time DeTomaso took him to a meeting in Detroit where they were working out the details of the Panterra with Lee Iacocca. Iacocca just about lost it when he learned that Tjaarda, the head designer for an Italian firm grew up just around the corner in suburban Detroit.

He was a talent and a fine gentleman.

Last time I saw Tom was at Cafe Rustica in Carmel Valley during ‘Holy Week’ last August where he was surrounded by a large table of friends and enthusiasts of his creations.

We had judged a class of Ferraris together at the 6oth Anniversary Celebration in Modena and one of the cars in contention was a 365 California Spyder. Tom was ever the sensitive gentleman and thought it might be unseemly for him to be involved in awarding a special place to car he had designed. But, as the car had risen to its position fairly based on objective judging he allowed himself to be overruled. Tom will be missed.

One of a group of Americans in Turin I remember well as I do the day I saw his Mangusta at the Carrozieri section of the Turin Show. There was one summer evening in the Colina when he introduced me to vodka from the freezer, still my favourite summer drink. I miss him and the whole group of car people during that magic period inTurin. Addio

Tom made a great life for himself in the designing of cars, a profession to which he certainly contributed greatly. It all happened because of his talent and willingness to work hard. I also saw him last August at Concorso Italiano where we spoke briefly. He was rushing as usual as there were many demands on him which I am sure he enjoyed immensely.

Looking back on that period of time in Turin shows that he was one of the great contributors to the emergence of Italian design as a unique expression in the creation of automobiles. He was in the right place at the right time and he made the most of it. Creativity is a process that applies to all human endeavor and it is true that the aesthetic execution of creativity makes us desire some things, sometimes simply because they are beautiful. Tom knew how to do that.

DICK RUZZIN

Only now have I become aware of the death of my great friend Tom Tjaarda. I first met Tom when he was working as a designer at OSI in Turin, later at Ghia nearby. I covered the press launch of the Pantera when we got to know each other better.

He and his wife became very special friends of myself and my wife Annette, always first on our list when we travelled to Turin. I was just thinking about him as we are planning a visit later this year.

Noteworthy is that when my company oversaw the search for stylists for a new mid-engined sports car to be built by Zastava, Tom’s design was the winner. It was the one that combined flair with practicality in just the right proportions — typical Tjaarda design. I’m sorry we never were able to build it.

Ciao, Tom. We’ll miss you big time.

tom took bill Pryor and me to look at a cisitalia for sale in ’66. they were asking $6k if I remember correctly. too much of a blobby shape for my personal aesthetic. that’s why they make chocolate and vanilla. and pistachio. what a neat guy; we talked at length at dinner at the Baton Rouge concours in ’11.