December 12th, 1959, Sebring. Tony Brooks' chance at the world title. He would finish third. Photo by Robert F. Pauley.

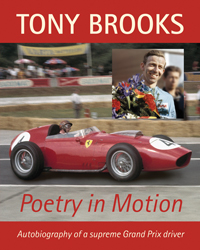

Poetry in Motion, by Tony Brooks

276 pages, color and black and white photos, 8.5 x 11 inches

Motor Racing Publications, Croydon, England 2012

ISBN 978-1-899870-83-7

By Pete Vack

Tony Brooks arrived on the racing scene in a very big way, winning the 1955 Syracuse Grand Prix with a Connaught Type B. It was only his third Grand Prix and he became the first British driver/car combination to win a Grand Prix race since Segrave’s victory at Tours in 1923 with a Sunbeam.

Four years later Brooks was the number one driver on the Ferrari team. By the end of 1959, he was within eight points of winning the World Championship, which would be decided at Sebring on December 12th between himself, Moss and Jack Brabham. Brooks had already done well that year, winning at Reims and the Avus Ring in Berlin, competing against the fast and agile rear-engined Coopers. At Sebring, he had a chance to cap a great racing career.

In his excellent autobiography, “Poetry in Motion”, Brooks provides a unique insight to those epic years of racing in the 1950s. At Sebring, everyone had a good time laughing about how Harry Schell, always good for practical jokes, cut across the infield during timed runs and posting a time good enough for the first row, despite driving an old F2 2.2 liter Cooper. This was hilarious enough to be clearly remembered by some 52 years after the event. But as Brooks reminds us, it was no laughing matter, for it was he who unfairly got pushed out of his rightly earned spot on the first row of the grid, next to Brabham and Moss.

The Ferrari of von Trips is damaged in the first turn as it rammed into the back of the Brooks Ferrari. Photo by Robert F. Pauley.

Tavoni cried foul but Schell pushed the Cooper to the front row and that’s where he started from. An unintended consequence was that on the first lap, von Trips, in another Ferrari 246 and eager to make a good showing, rammed Brooks forcing him off the track. A pit stop to determine damage would, and did, mean Brooks lost his chance to win the Championship. Moss retired, Brabham ran out of gas on the last lap, Bruce McLaren won and Brabham pushed his car over the line to finish in fourth and with those points won the Championship.

Jack Brabham and John Cooper enjoy the finish of the first U.S.Grand Prix, held at Sebring. Brooks would finish third, Jack fouth, but won the Championship. Photo by Robert F. Pauley.

There would be two years left for Brooks in F1 racing; neither would be satisfying. After a steady climb up the ladder, driving for Connaught, BRM, Aston Martin, Vanwall and then Ferrari, by 1959 he was at the top. But in 1960, thinking he needed more time to devote to his family and future in Weybrigde, he left Ferrari for a second rate Yeoman Credit Cooper team and an aborted Vanwall project. In 1961, he tried with BRM, but the underpowered four-cylinder was neither fast nor reliable, and the promised V8 did not come on the scene until 1962. His remarks and attitude of those last two difficult years is telling; there is no doubt he was not happy with any of the three teams he had to deal with. The times were changing, the cars were changing, and yet it was still a risky business.

Brooks had found great joy in precisely drifting and cornering with a high-powered front-engine Grand Prix car, reflected in the name of the book. For him, the classic four-wheel drift was “Poetry in Motion”. With the coming of the rear engine and the much lower power of the 1.5 liter cars in 1961, racing lost much of its attraction. He retired to concentrate fully on his third career as the owner of a dealership in Weybridge, which ironically – or perhaps fittingly – backed up to the old Brooklands track. Brooks literally took it from a sleepy four pump filling station to one of the most successful Ford dealerships in the area. At the age of 61 in 1993, Tony Brooks retired once more, this time for good.

Brooks had found great joy in precisely drifting and cornering with a high-powered front-engine Grand Prix car, reflected in the name of the book. For him, the classic four-wheel drift was “Poetry in Motion”. With the coming of the rear engine and the much lower power of the 1.5 liter cars in 1961, racing lost much of its attraction. He retired to concentrate fully on his third career as the owner of a dealership in Weybridge, which ironically – or perhaps fittingly – backed up to the old Brooklands track. Brooks literally took it from a sleepy four pump filling station to one of the most successful Ford dealerships in the area. At the age of 61 in 1993, Tony Brooks retired once more, this time for good.

Tony Brooks, born Charles Anthony Standish Brooks in 1932, was a natural driver. He never went to driver’s school, never had a mentor. He was self-taught, self-motivated, extremely intelligent and knew what he wanted to do after the first time behind the wheel of his mother’s MGTC. His father, a successful dentist in the town of Dukinfield, loved motor racing and after the war bought a Healey Silverstone to replace the MGTC. Brooks had a lot of family encouragement and was soon the owner of a BSA motorcycle. He was off.

But not quite. With a mature sense of what was good for him, Brooks went to dental school and in 1956 after almost six years of “intensive study” graduated with full degree in Dentistry. He knew that he would have a way to earn a good living if and when he chose to stop racing. That is wisdom.

Goodwood, 2012. Brooks and Gurney together in the Ferrari TR they shared at the Goodwood TT in 1960. Photo by Hugues Vanhoolandt.

Up to now, Brooks has refused to tell his story, preferring to keep a relatively low profile (at least compared to his friend and long-time competitor, Stirling Moss). But now, Brooks can do the ultimate Monday morning quarterback routine, and he makes good use of the many biographies and histories already published about the era. In that sense he may well have the last word as everyone else has either published or perished! Approaching his 80th birthday, he finally gathered up the copious notes, photos and letters he had accumulated from his very first race and put together an enjoyable, accurate, telling picture of a life well-lived in the midst of far too many deaths.

The 1950s witnessed the greatest number of drive and spectator deaths as the number of events, speeds and number of participants increased all over the world but the tracks and safety equipment lagged far behind. Brooks drove through the carnage…literally, as he did at Le Mans in 1955 when he threaded his way through the accident debris caused by the wreckage of the Levegh Mercedes. His father and brother were also there, watching the race from the grandstand, just above and to the rear of the earthen barricade where the majority of the spectators were killed. All three Brooks survived that day.

But it fazed them not. Brooks’ father never discussed the subject with him, and “he seemed to accept that motor racing was what I wanted to do and that he was prepared to suffer the worry associated with it.” As with so many other drivers, when one of their number died at the track, the attitude that “…this can’t happen to me because I don’t make mistakes” came into play. How else does one survive? Notably, Brooks never discloses what his Italian wife Pina said or thought of the dangers of racing, nor those of his mother.

Throughout the book, Brooks is honest, forthright, frank and yet for the most part, very kind and generous to the point where when he describes those last two miserable years, the criticisms are somewhat jarring, but not inaccurate. While the ten years of racing takes up 90 percent of the book, Brooks does discuss his career as a franchised Austin, Fiat and later Ford dealer. It took a lot more time an effort that he anticipated but it was rewarding. He was able to provide a top-notch education for his five children and remains married to Pina to this day.

Brooks and Gurney again in the Testa Rossa. After retirement, Brooks enjoyed particapting in such events, but never raced. Photo by Hugues Vanhoolandt.

A necessary fault of “Poetry in Motion” is the page upon page of describing the events of each race in which Brooks took part. Even after retiring from an event, we still get a blow by blow of the rest of the race, much of it written at the time and taken from his contribution to motoring magazines of the era or reports from journalist such as Denis Jenkinson. Without it the book would be lesser, but with it, hard to plow through at times. Given the choice, however, we’d keep every word.

One last comment…the photos in the book are numerous, excellent and relevant BUT are reproduced as 4 by 4 inches, 3 by 3 inches in most cases and less in others, when the images beg to be full or half page in size. Almost all are black and white, even though it would have been a great opportunity to finally be able to use and publish the rare color images that were taken but too expensive to publish in the era. And NOTE…the color images in this report are NOT from the book, but taken by Robert Pauley in 1959 and Hugues Vanhoolandt at Goodwood in 2012.

The publisher lists a “Klemantaski Edition” as well, but we have not had a chance to see it.

Racing historians, this is a must have. And catch the 35% off sale that we can offer until December 31st.