By Paul Wilson

I enjoyed my Alfa 6C2500 project so much that finishing it creates a problem: what next? Without a major dream to focus my thoughts on, I knew I would feel aimless and lost. So a few years ago I began to consider the possibilities.

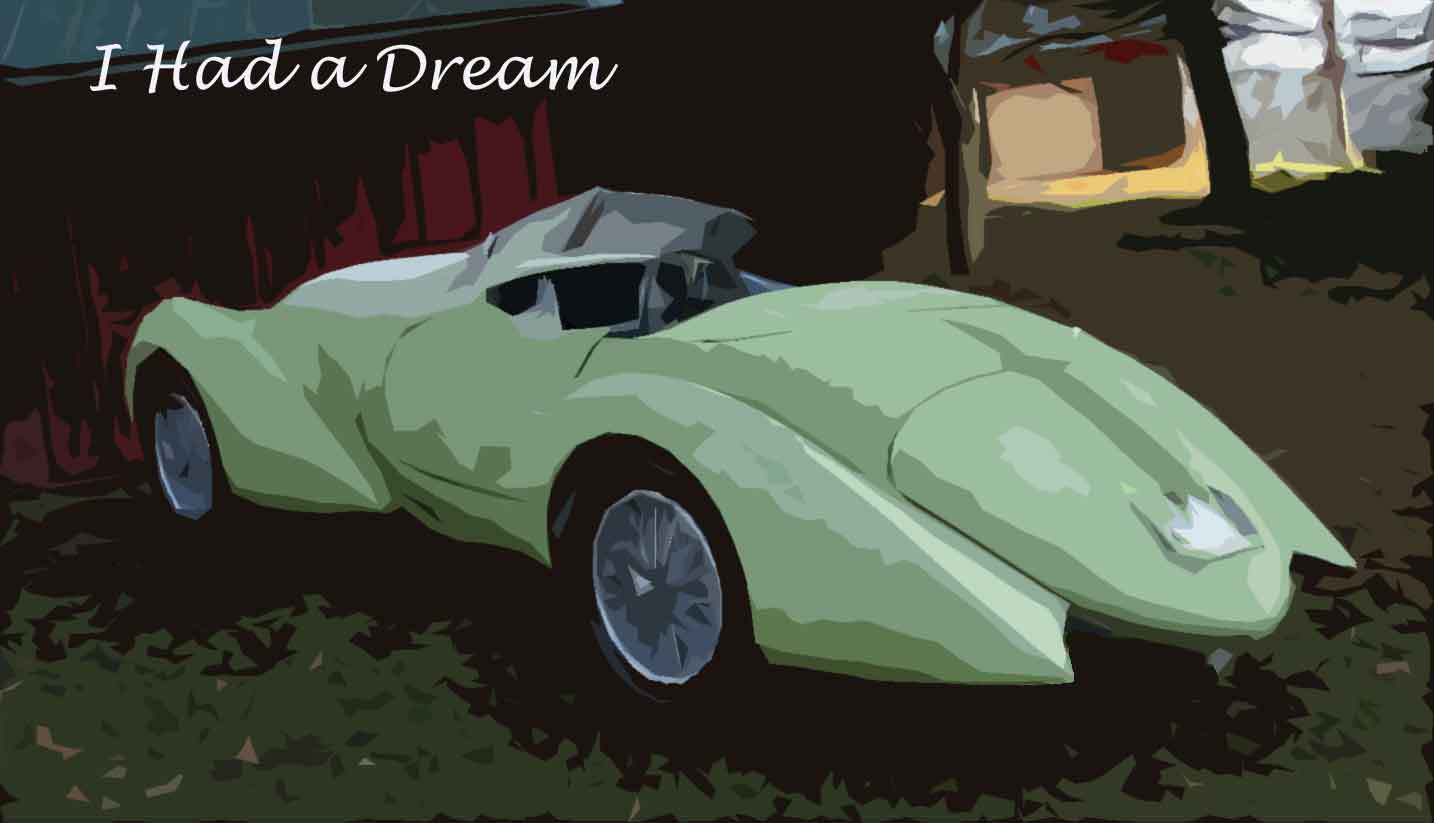

With the coupe almost done, a roadster simply had to be built, a feat to be accomplished because it wasn’t there.

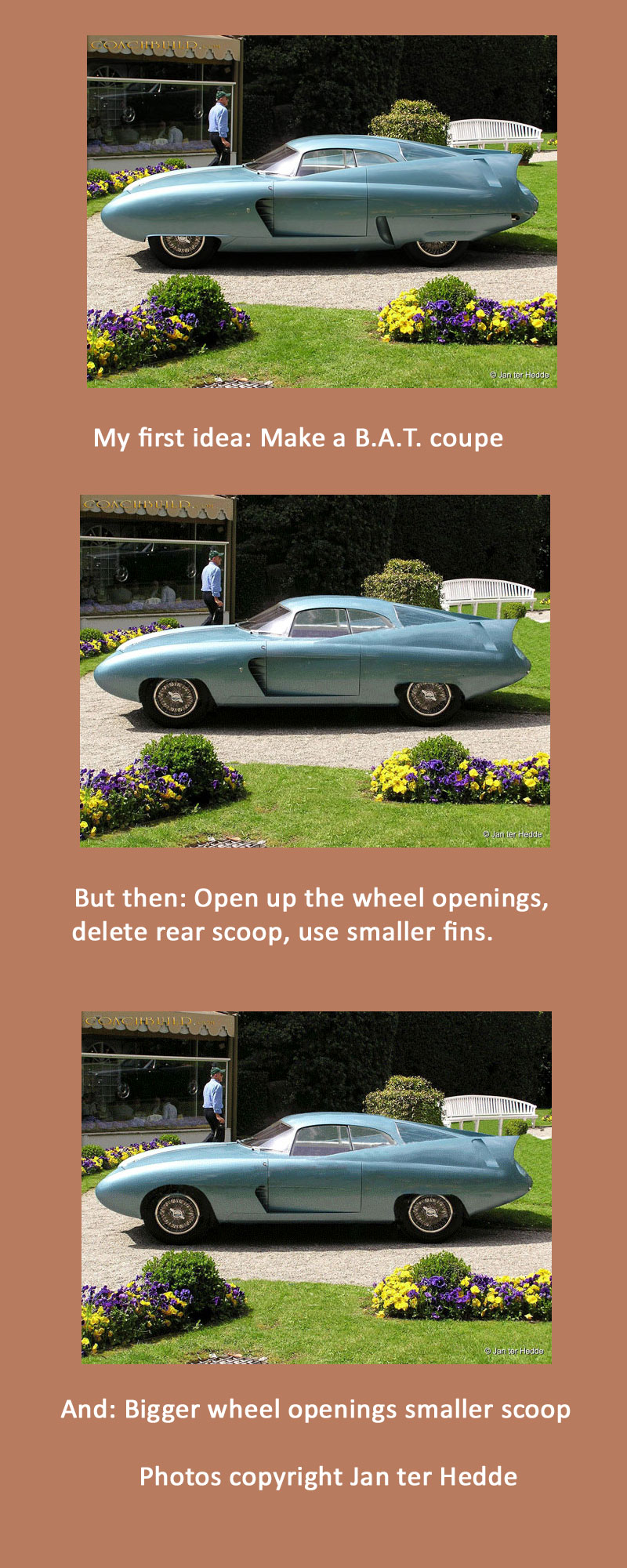

I hesitate to mention my first idea. The long-feared Men in White Coats might appear at my door, with such proof of incurable insanity. But–how about a BAT? They’re really, really cool. And wild, showing the outer reaches of imaginative design in the early ‘50s. Air flow was the dominating concern–they were explorations of “aerodynamica,” the A in BAT. Smooth, rounded shapes would slip through the air with the least resistance. Enclosed wheels kept them out of the airstream. Ducts carried cooling air in and out, for the engine and brakes. And those spectacular fins shaped the flow over the rear body.

But even BAT 7, my favorite, has features I would change. I like seeing wheels. It has too many scoops and vents. I don’t mind sacrificing rear vision, and in-your-face impracticality is a lot of its appeal, but at least I’d like to be able to see out the side windows. I spent some time with Photoshop, experimenting with different modifications.

The original cars were built on an Alfa 1900 chassis. A friend has a 1900 parts car I could use for mine, so it would be authentic. The roof and side windows of BAT 7 resemble those on a VW Karmann-Ghia, so I dragged home a K-G donor car. Admittedly farfetched, the project didn’t look impossible.

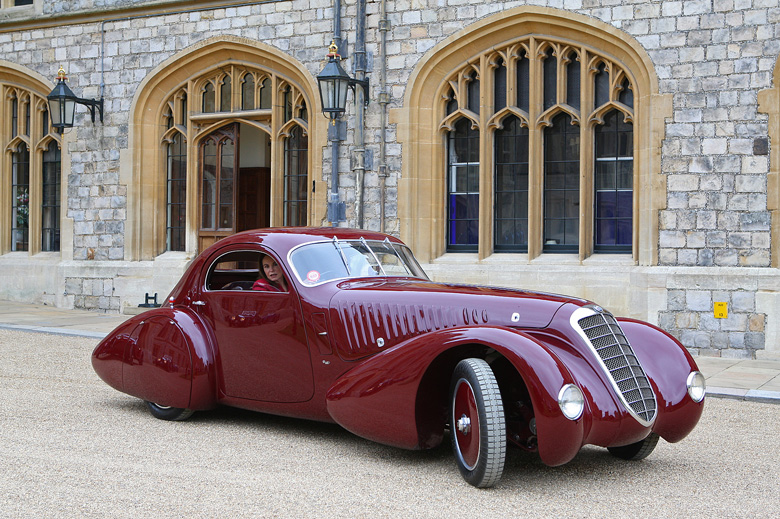

Another idea for a future project, really my first choice, was making a 6C2500 roadster to match my coupe. These were originally coachbuilt cars, so mine would still be a real 6C2500, just rebodied. I had a couple of engines and other 6C2500 spares. With its all-independent suspension and gorgeous twin cam engine, it has exotic specifications. Its 18″ wire wheels give it an aggressive stance. And it’s a perfect size: big enough to command attention, but still a true sports car. Any bigger, and its character would change to a luxury tourer, heavier, more comfortable, more sedate.

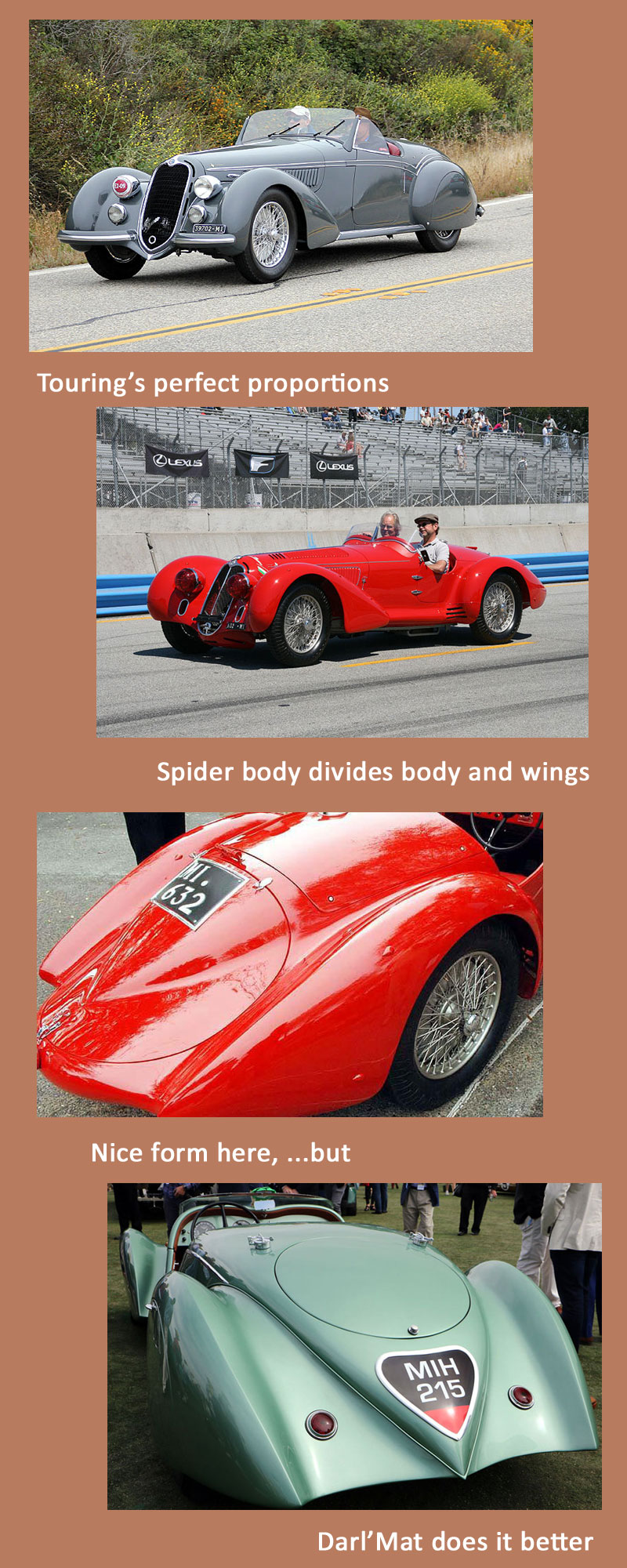

If I could do another 6C, what would it look like? As with the coupe, it would blend the most appealing features of cars a late ‘40s designer would be familiar with. We can start, of course, with the Alfa 2.9. The Touring roadster is surely one of the most beautiful cars ever made: perfect proportions, graceful fender shapes, long hood. But comparison with its racecar sibling, the 2.9 Mille Miglia, suggests possible variations. At the rear, the MM’s narrower central fuselage divides the “tail” from the “wings.”

>

I love the MM’s rear fenders, but I’m not so sure about the central area where the end of the fuselage forms a bullet above a bland lower area. On the Peugeot Darl’Mat the middle part tapers to a point to match the fender shapes, with smooth connecting panels in between. I love it (for many years I had the Darl’Mat now in the Simeone collection), but maybe there are further possibilities. I don’t like the heart-shaped license plate compartment, though to be fair, it’s hard to find any attractive way to put on a license plate. The central section should have more prominence than the fenders. Maybe the fenders could sweep in more dramatically.

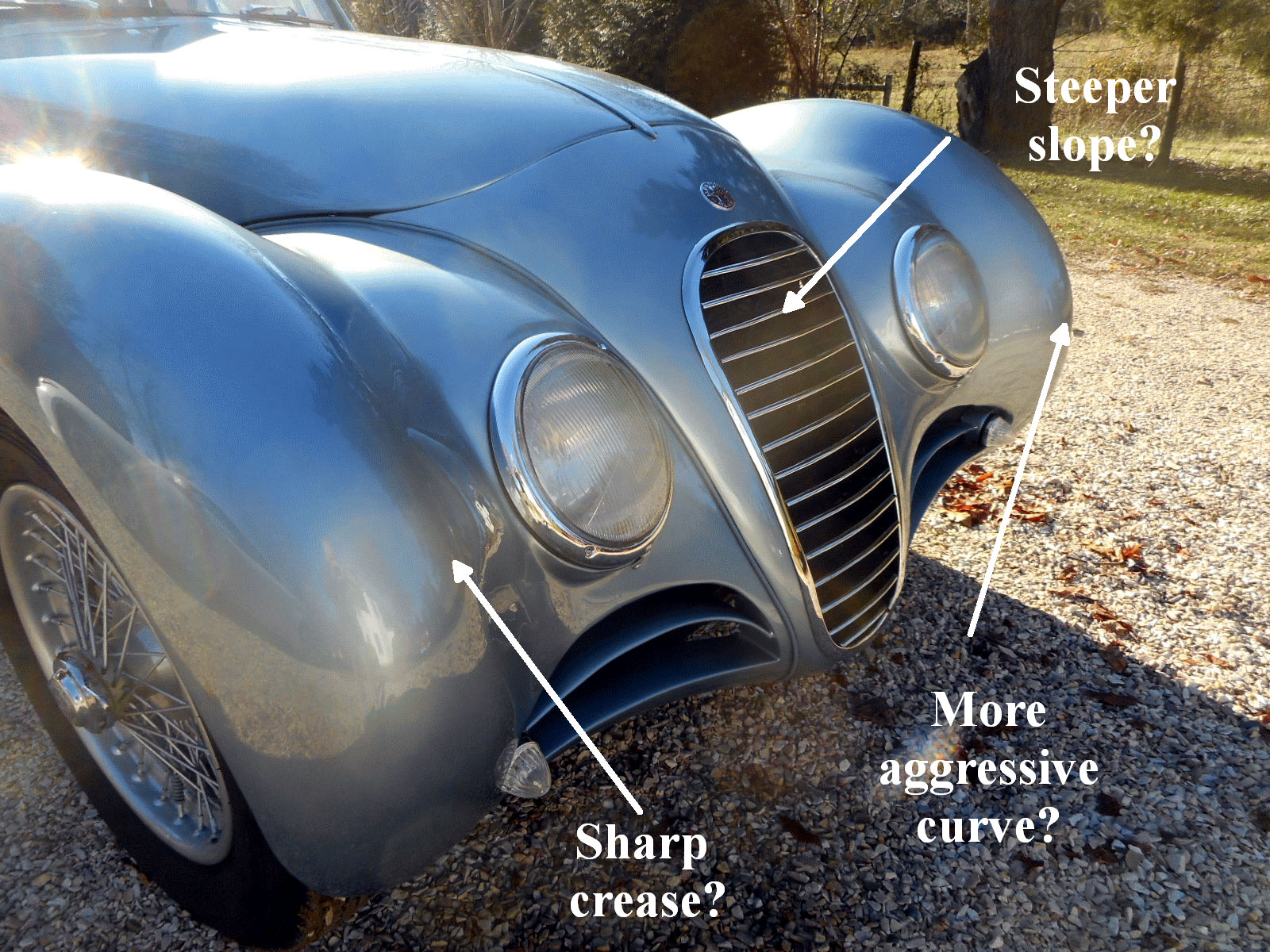

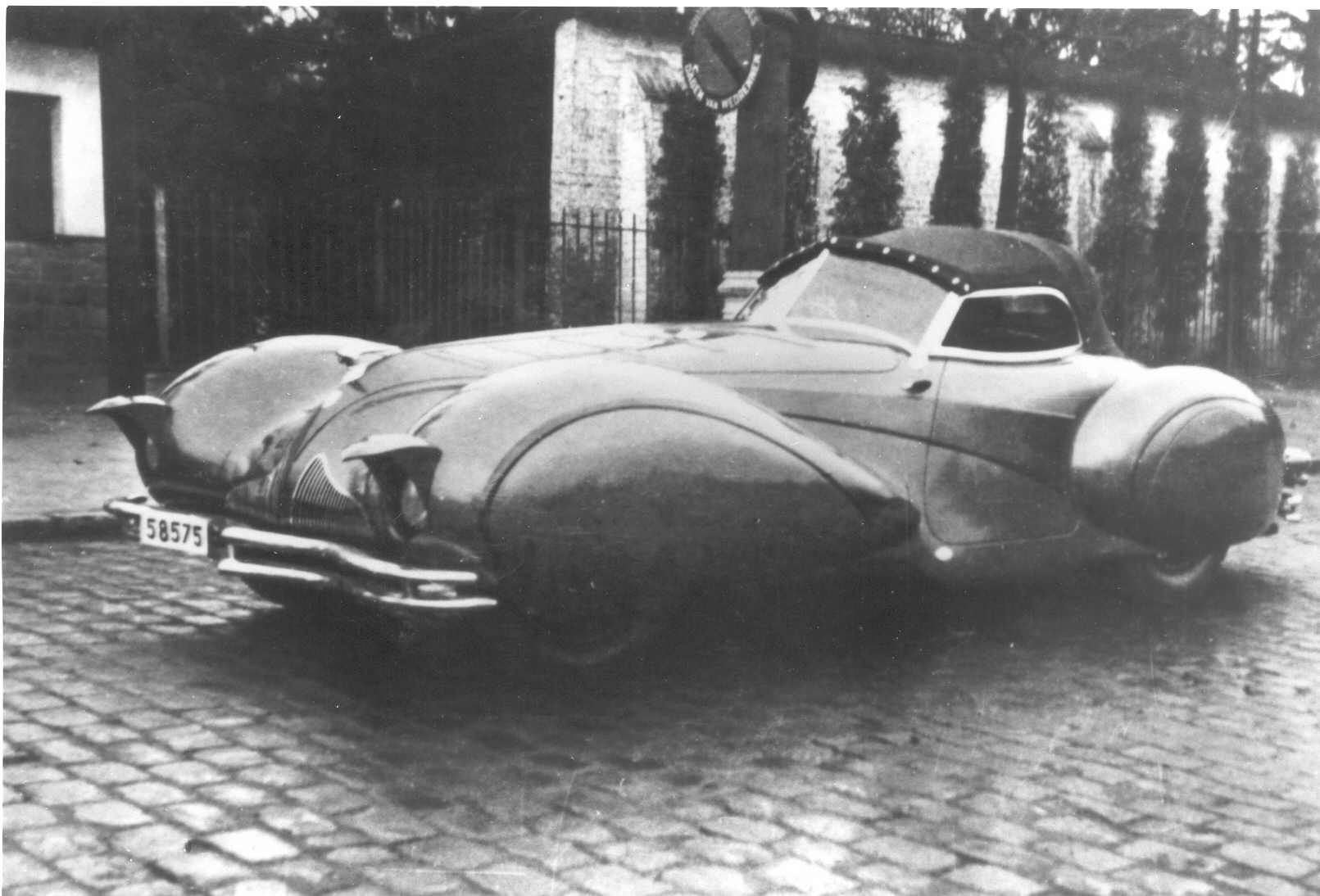

Notice the slight creases at the crown of the fenders of this “Bugelfalte” roadster. More accentuated creases can be found on the Arnolt Bristol and DB3S Aston Martins.

The BMW 328 “Bugelfalte” roadster is another stunning design from the period, particularly successful in its simple, graceful front end. Having the engine and radiator much further forward than most prewar cars was a challenge that led to many clumsy solutions. On very different chassis, the great ‘30s classics didn’t give relevant answers. “Bugelfalte” translates to “trouser crease,” describing the peak at the fender tops. It’s an attractive detail, seen later on the Aston DB3S and in more emphatic form, on the Arnolt-Bristol. The BMW’s fenders are integrated into the body sides. I prefer the earlier look on a late ‘30s Zagato Alfa, a muscular torso connecting separate fender shapes front and rear.

My coupe’s front end would give a good starting point for its roadster sibling. But I like the steeper slope of the grille on one of the last 2.9 chassis. And the fenders might be more exciting with the BMW’s sharp peaks and a more aggressive front profile.

A body built just before the war by De Mola, an obscure Belgian firm, suggests further possibilities. Now on a 6C2500 chassis, it has a complicated history. In its original form, it had fully enclosed front wheels and headlights hidden under flip-up covers; when restored, it was slightly less radical. It still had high-set fenders, painted banners sweeping back in a contrasting color on the body and fenders, teardrop-shaped front wheel openings, and other wild details. If some features went a bit too far, its huge wire wheels, raked vee-windshield, and perfect proportions were a magical combination.

These pleasing fantasies ignored two huge problems. First, finding a 6C2500 chassis looked to be impossible. From 1939 to 1952, perhaps 1200 such cars were built. Probably a majority were scrapped. Survivors are now very valuable. Times have changed since I bought three for $1000 in 1975.

An equally daunting problem was pointed out to me by a friend. “Let me get this straight,” he said. “Your coupe is almost finished after 40-some years. And you’re how old? By my calculations, if you work with the same speed and efficiency on a roadster, it will be done in 2060, when you are 116 years old. Can you do arithmetic?”

If I were sober and sensible, I would have dropped the idea. Luckily, I didn’t. Stay tuned.

I love the look of those cars, but you must have insane amounts of money to pursue these ideas….

I would leave well enough alone, it’s history after all…

Restoring old historic cars, I can well understand, BUT, what you are doing is just because you can, with money, and frankly I find that rather crude and unnecessary…using a VW Karmann Ghia to modify an Alfa???

Sorry

Alan

Whether the project goes any further in actual execution, I just love the thought process! Keep goin’! Can’t imagine though any more perfect design than the Touring 2900s of Ralph Lauren (ex- Phil Hill) and Chip Connor. I would kill!

Alan, I have to disagree.

Apparently Mr. Wilson has the time and the money to make some of his dreams come true. He’s creating art, no different than painting a picture or creating a sculpture; it’s just on a grander scale. If I had the wherewithal and the time, I’d try to make a personal copy of the Aston Martin Bulldog, or an Aston Martin DB2 Barchetta, or of the unbuilt, Porsche-designed 1935 Auto Union Type 52 Sportlimo (google it, very retro-looking).

BTW – the Karmann Ghia roof and window shapes are very, very close to that of the BAT; why shape from scratch something which is already available. Recall that the (albeit outrageous) Clenet used part of a Sprite body for its bustle!

Cheers!

It will be interesting to learn of Paul’s comment to my suggestion of an outrageous colour!

Peter

I’m flattered that Alan Leslie thinks I’m part of the wealthy 1%. But the projects I dreamed about wouldn’t take “insane amounts of money.” For the BAT, I bought the K-G parts car for $300, my friend’s parts car chassis wouldn’t have been much more, and materials to build the body might have added up to $1000. Other than that, it would have been just a normal restoration–mechanicals, upholstery, paint, and so forth. I’ll go into more detail in later installments of this story, but body fabrication isn’t expensive. It does take time, which I’m lucky to have.

Come on mannn, that’s a great project!!

Well done Paul! I loved the first articles on the coupe – and now describing the steps in reaching the ‘right’ design is fascinating stuff. And yes it does take a lot of time ( my little Lancia took ages !! ) – I look forward to reading m0re….

I would encourage Mr. Wilson to follow his dream. I own two replicas of great cars that I could never own – Ferrari 250 GTO (coupe) and Testa Rossa (roadster). They are magnificent styling creations, never to be surpassed and it is a continuing joy to observe them in their matchless Italian glory . . . and to drive them in vicarious pleasure of the halcyon days of true motor racing.

Tom Wall – Oakton, VA

Paul is beyond an automotive enthusiast, he is an artist. I have owned three of the cars he admires above, but I envy much more his talent. The the few really creative can have a dream, but far, far fewer have the ability to consummate the dream with their own hands. Let the critics look at pictures of the objects of their desire, while you can reach out and them.