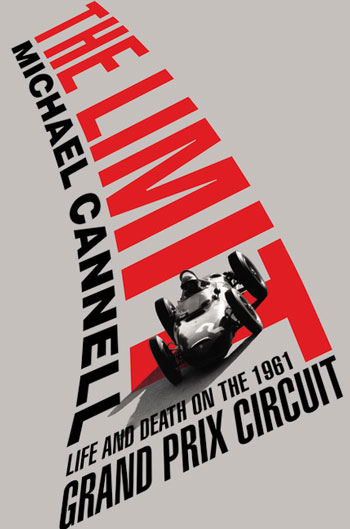

Last week we published an interview with New York Times writer Michael Cannell, whose new book has been greeted with great reviews. This week, Michael T. Lynch reviews Cannell’s book “The Limit, Life and Death on the 1961 Grand Prix Circuit”. It’s a review you will NOT want to miss.

Review by Michael T. Lynch

Author and journalist, Michael Cannell, whose sports writing has been seen in the New Yorker, the New York Times, Sports Illustrated and Outside, has written a book about one of the most dramatic seasons in World Championship Grand Prix history. The book, “The Limit – Life and Death on the 1961 Grand Prix Circuit”, covers the first year of the 1.5-liter GP formula, which featured a year-long battle between Wolfgang von Trips, a German Count and Phil Hill, a Southern California private school kid whose interest in cars had led him to drop out of the University of Southern California and become a mechanic. A mechanic, who from the beginning was lucky enough to work on some of the great cars in automotive history.

The book begins with bios of the two protagonists and the man whose cars they drove, Enzo Ferrari. It describes what was then a deadly sport – five drivers on the Ferrari team alone lost their lives racing in the 1956-61 period. There were many others. The blood and gore sometimes lapses into signature Italian sportswriter breathlessness, but perhaps this is justified considering the operatic nature of the story. Here is part of the section on Alfonso de Portago’s fatal 1957 Mille Miglia crash. “A policeman described how they found half of Portago’s body on the left side of the road and the other half pinned under the car on the right.” Other notable crashes of the era, like the 1955 Le Mans disaster, in which over 80 died when a car went into the crowd, are presented in equally graphic terms.

SUPPORT VELOCETODAY BY BECOMING A PREMIUM SUBSCRIBER

For the general public, and even enthusiasts too young to remember the period, the book is a real page turner. Cannell’s sports background has taught him that the real story is not the contest, but the people taking part in it. He has done a remarkable job of collecting anecdotes about many of the characters and the lighthearted and tragic moments that made up the highs and lows of the era, including some this scribe had not previously heard. For this reason alone, it can be recommended to readers familiar with the times, and they will enjoy the fleshing out of situations they may only vaguely remember.

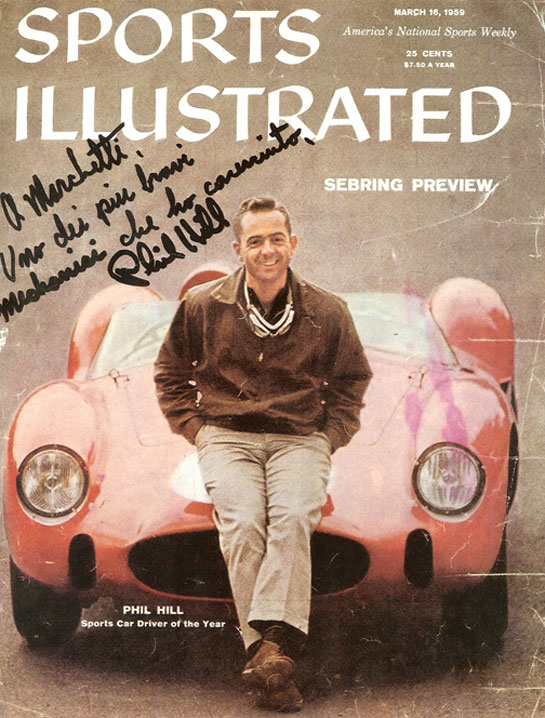

Phil Hill poses with a Ferrari 250 Testa Rossa on the cover of Sports Illustrated’s 1959 Sebring preview issue. The inscription is to Adelmo Marchetti, one of Ferrari’s most energetic mechanics. It reads, 'To Marchetti, one of the best mechanics I ever knew.'

.

Where the book has problems, they arise from Cannell’s unfamiliarity with motor racing and the period involved. Rather than nit pick errors only an historian would notice, the Editor and I have included a link to an errata sheet of some forty odd items. We have also included a link to a second document in which Michael Cannell has been kind enough to take issue with some of the nits we picked. For those who know the times, these will grate like missed notes during a great symphony performance.

A book is not a screenplay, but Cannell takes the liberties of that genre to create contrasts between characters and exaggerations of situations that already had drama enough. As we know, once something is in print, it is as if it is graven in stone to future researchers. In the book, there are errors that distort the historic record that need to be addressed.

Even before he’s out of the Prologue, Cannell casts the struggle for the 1961 World Championship as being between a, “Backstreet hot rodder and a German Count.” He deprecates Hill’s father as having, “the mindset of a lifelong public servant.”

Phil Hill was every bit of the aristocrat that von Trips was, only we don’t have titles in America and Trips’ family home was larger. Phil attended private schools, his family had a chauffer, he went to college at prestigious U.S.C., had dance and music lessons and had parents well known in their respective areas of endeavor, all evidence of the American upper class of the time. Perhaps most telling of all, Trips began racing at the lowest level, on motorcycles, before stepping up to clapped out Porsches, while Hill early on drove the pre-war Alfa 8C-2900 now owned by Ralph Lauren and recently shown at the Louvre in Paris. Hill also raced his own Ferraris, the most expensive cars of the day, early in his career.

Hill’s father held executive positions during his business career, before becoming the head of the Los Angeles Grand Jury and then, Postmaster of Santa Monica, both positions denoting community leadership at the time.

Not being of the period, Cannell writes that, “Americans viewed sports car drivers as suspect athletes engaged in a bastard sport like surfers or bull riders.” This is an opinion belied by the facts, as Fortune 500 executives as well as other noted leaders in entertainment, politics and the arts took part in the newly emerging sport. It was widely covered in the leading sporting weekly, Sports Illustrated, from the time of its founding in 1954 and the magazine later presented a Sports Car Driver of the Year Award annually, while virtually ignoring oval racing except for the Indianapolis 500. Local newspapers often reported the races and their ancillary events on the Society pages, because of the prominence of some of the competitors.

To enhance his story, Cannell claims Ferrari sometimes acted like, “a humble Italian workman like his father.” Ferrari’s father had a metal working business that sometimes received contracts from the Italian railway system that involved employing large cadres of men, hardly the hallmark of a humble workman.

Trips personality obviously resonated with Cannell more than Hill’s and the storyline makes Trips out to be a better driver than Hill, at least by 1961. The racing record does not bear this out. To accentuate this storyline, Cannell claims that Hill never regained the form of his 1961 season. There is some truth to this if one limits Phil’s racing efforts to Grand Prix racing. But Hill continued to win World Championship sports car races after 1961, including his final professional race in 1967 at Brands Hatch in England. He also won a Can Am race in 1966, when Can Am cars were faster on a given course than Grand Prix cars and the top GP stars took part in the series. The fact is that Hill won five World Championship sports car races after 1961, four more than Trips won in his entire career.

Therefore, the book is an enigma to this aging historian, even though I recommend it highly for its breadth of detail in the years leading up to the 1961 season, and the facile description of the tension of the championship contest in that year. Cannell has included great chapter notes but not backed them with a corresponding bibliography. I am flattered that I found my name in the credits, and Cannell’s efforts to find me speak to the seriousness of his research.

“The Limit” is a great read, has received almost uniformly positive reviews in the popular press and will prove satisfying to the vast majority of VeloceToday readers. However, a few cognoscenti will know the score well enough to hear the sour notes.

Click here to see a Word Document Errata Sheet: Limit Errors

Read Michael Cannell’s Response

It is seldom that “social classes” are mentioned in America, so it’s hard for someone coming to the field from outside to really picture what “class” somebody was 50 years ago. If you think of Santa Monica as a small midwestern town you can see how important the position of postmaster was when Hill was growing up. And USC was like going to Harvard, at least to Los Angeles folk. It is confusing to those coming new to the field that Hill seemed to be satisfied with a “blue collar” job like being a mechanic (I think someone used the phrase “lowly mechanic” in the publicity) but since he was racing while being a mechanic this can be explained by being considered to be a subtrafuge getting around the problem of sports car drivers not being paid for their victories (in the beginning in America it was the sport of gentlemen; who being monied, didn’t need to race for mere dollars). Ken Miles did the same for the dealership where he was a service manager for a Porsche dealer in Beverly Hills–collecting a salary for his “job” while in reality he was being paid to race. Recently I heard from someone who says Phil Hill even visited Jaguar dealerships across the country to tout new models; in effect he was a spokesman, far above a “lowly” mechanic (I only use this word because someone else did; but think some mechanics are geniuses like Phil Remington).

As far as races done after 1961, the intent of the book was to build up to the year 1961. I myself am more of a sports car man so am more interested in why Hill left (or was uninvited, as he told me) to be on the Ford GT team in 1966 at LeMans, and why he went to Chaparral when Jim Hall was known to be more interested in experimenting with new ideas than in finishing a race, but all that’s fodder for a full biography of Hill –a different focus than Cannell’s book.

Anyway I hope the next edition will benefit from Mr. Lynch ‘s scholarship and hope I can talk him into reading one of mine with his red-inked pen.

I had the good fortune of being present at the Grand Prix of France in 1961. Held on the awesomely fast Reim’s course in the middle of hayfields and on public roads, we were watching the race from the Virage De Thillois grandstands, an almost hairpin turn with an escape road off of it. The Ferraris were brilliant and outclassed just about everything, but the scrappy Stirling Moss in a Lotus, did his best – even laying back on the escape road waiting for the red cars to sweep through and joining them in a dice out of the corner!

Gee, not another “G.I.s brought home MGs from England” line. Repeated endlessly over the years without proof of same. Truth is, you could probably count the number of MGs brought home by service personnel on both hands. Wish we could lay that line to rest but it just keeps getting repeated.

My sincere thanks to Michael Lynch for his review and errata compilation. Over the years we have seen mistakes and misinformation published, thereby becoming part of written history, only to be repeated by the next author researching the same subject. And so it will be with this work, which Mr. Cannell himself identifies as “non -fiction”.

Michael,

Thanks for the review and insite. I just bought the book today and am anxious to receive it. Having lived through those days I would read everything about the races that season I could. The US did very little reporting on European racing at that time and it was always about four or five months late to print. I was devastated when, my presonal hero at the time, “Taffy” Von Trips was killed . I hope that the facts of the ensueing trials as well as the facts of Jim Clarks involvement in that accident are fully covered. We never saw much in the day as to the final findings of the courts. Should be interesting if the added drama doesn’t overwhelm the real story.

I too want to add my thanks to Michael for the fine review. I had just gotten interested in motor racing and the 1961 Grand Prix season was the first one I followed. I remember as a mid-teen being shocked and upset by the news in Sports Illustrated about the accident at Monza. I share Logan Gray’s concerns. I know drama sells. However, it is also important to get the story right.

Cannell’s responses to errors and omissions are inadequate. I stand with Michael Lynch and Pete Vack for accuracy and do not accept that the faults are trivial. Knowing what one is writing about in depth can only enhance the end product.

Cannell’s On the Limit is also quite similar to Robert Daley’s The Cruel Sport. Daley covers the same material, but was present during the season in Europe and actually interviewed both Hill and von Trips before Monza.

author claimsMoss only drove private cars except Mercedes team;guess he never heard od Vanwall or Maserati factory drive 1956

Cannell mixes things up like mush also on p. 38: “…Mercedes team that had resumed racing that year (1952) with the experimental 300 SL coupe, a low-slung silver roadster nicknamed the Gullwing because its doors hinged upward…”.

Well, a coupe is a coupe and a roadster isn’t a coupe, it’s an open 2-seater and the roadster was not the Gullwing, that was the coupe. Actually at the Carrera Panamericana – the context of Cannell’s discussion – Mercedes fielded both coupes and a roadster.

It’s the conflict of obvious details like this that leave the reader with a nagging suspicion of the “truthiness” of all the other facts an factoids presented in the narrative.