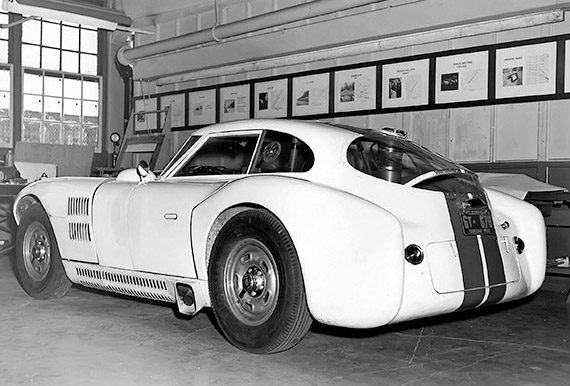

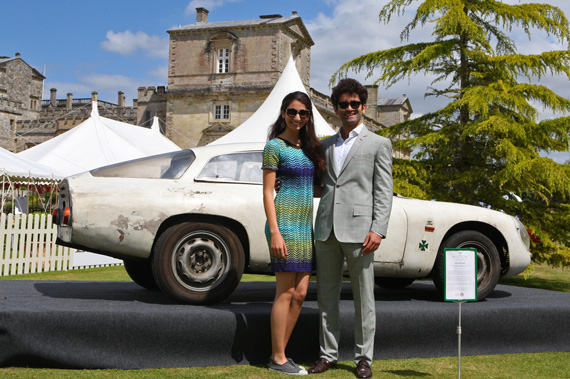

Corrado Lopresto’s recent find as displayed last weekend at the Wilton Concours. Jonathan Sharp photo.

Story by Pete Vack

The world of the Internet will likely soon be filled with stories of a particular Alfa Romeo that served as the prototype for a new Alfa Zagato GT, one with a long tail, suddenly clipped off and called the “Coda Tronca”. And so we add to the hoopla, for of course the prototype Coda Tronca as found by the long time and truly enthusiastic Italian collector Corrado Lopresto and introduced at the Wilton Concours last weekend, (see related story) is an important find and a truly significant Alfa Romeo and Zagato. In Part 1 we’ll look at the use of the Kamm effect and why the Alfa SZ Coda Tronca was different.

Winter, 1960

As Ercole Spada would later recall, these were exciting times. In February 1960, The 22 year old ex-soldier, lacking any kind of formal training, had applied for a job at Zagato upon completion of his military service. He brought with him no portfolio, no sketches. But he loved to draw cars. “While my friends were stealing a peak into Playboy, I had my nose deeply into car magazines,” Spada recalled. Elio Zagato asked him if he had a driver’s licenses and could draw on a one to one scale. Spada said yes and Zagato hired him on the spot. Before Spada came onboard, Zagato didn’t have a chief designer. Cars just more or less happened. Life was simpler then.

His first assignment was to design a body for Tony Crook’s Bristol 406S, which although high and narrow, was a great improvement over the earlier Zagato effort on the 406. Hot on the heels of the Bristol came the Aston Martin Zagato, and suddenly, with less than a year under his belt, Spada was if not famous, definitely had proven his worth. It was a story out of the dreams of thousands of boys, and Spada was living it.By the end of the year, Elio Zagato realized that the now famous Alfa SZ 1300 Veloce which had been a consistent class winner was at the end of its life cycle and now being defeated by the new Lotus Elites. Something needed to be done. And that’s when life really became exciting for the young Ercole Spada. With Elio Zagato, Spada would create a shape that would increase the top speed of the existing Alfa Zagato by five mph and finally confirm the aerodynamic theory put forward by Dr. Wunibald Kamm in the mid-1930s.

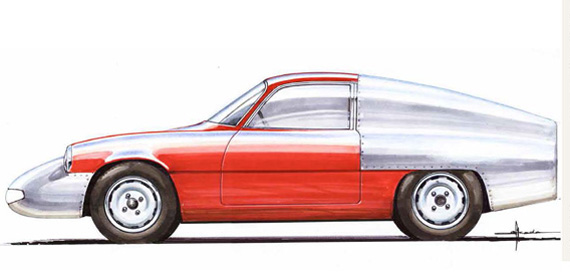

Using an Alfa SZ borrowed from the shop, Elio and Erocle added a long nose and a long tail to increase the speed of the somewhat dumpy looking SZ. They would try different shapes and test the car over the Milan-Bergamo motoway, timing it over straight stretches. This went on with no profound results until, according to Spada, he remembered an article about Kamm’s experiments in the 1930s and the Kamm tailed BMW 328 of 1940. So, off with the tail, they said.

Dr. Wunibald Kamm

Although Dr. Kamm and Baron Reinhard von Koenig-Fachsenfeld designed the BMW 328 Kamm back, according to Jerry Sloniger, Koenig-Faschenfeld* first discovered the “K” effect while streamlining a Vetter bus for increased speed on the Autobahn. He realized that the same cd figures as a long tail could be obtained by clipping it while saving space and weight. Few took notice however. After the war, Kamm often visited the U.S. and in 1952 was invited to Briggs Cunningham’s shop to help design the C-4RK coupe which would compete at Le Mans. The coupe retired at Le Mans in 1952 and placed 10th in 1953.

In this photo, courtesy of the book “Briggs Cunningham, the passion, the cars, the legacy”, we see that the C-4RKtrunk is not cut off as sharply as the Alfa Coda Tronca and has finned fenders.

It was faster than the open Cunningham’s on the straight, but uncomfortable to drive. The Kamm tail went virtually unnoticed as the D-Type Jaguar, a semi-long tailed affair with a fin, dominated the event for years to come. No one thought further of incorporating the Kamm effect; ironically, Jaguar, Ferrari and Maserati produced some of the most beautiful racing cars ever to set a tire on the racetrack during that era. The adage “if it looked fast, it was fast”, still applied.

Spada was aware of the earlier Kamm designs, but in his biography, Spada: a long story about a short tail, Spada noted something about the Kamm-tailed cars. “They had never cut the tails off sharply. It was always rounded smooth in one way or another.” Ercole and Zagato took a teardrop like shape and then cut the long tail, “as if we had a gigantic knife”.

If one takes a look at the BMW 328, that holds true. And Kamm’s own design for the C-4RK also indicates a more rounded tail, complete with finned rear fenders. Spada’s design, then, was in fact a new way to interpret Kamm’s theory. Interestingly, in the future, almost all attempts to use the Kamm theory featured a very sharply cut tail.

The Alfa Zagato 1300 Coda Tronca

The improvements were astounding, and at first they couldn’t believe it; a full two seconds off the timed kilometer and the top speed was registered at 227 kph.

By the spring of 1961, a prototype had emerged from the Zagato shop, and in June Elio took the car to Monza where he convincing won the 1300cc GT class. There was no longer any doubt that the Coda Tronca concept worked like a charm. At first, Elio Zagato named the new car the SZT, “T” for Tronca, short for Coda Tronca. But the model name never caught on, and the 44 or so clipped tail Alfa Zagatos made were called clipped tail or coda troncas.

The new car had a short life, as the Alfa 1600 was introduced and in turn led to the dynamic GTZ 1/2, which was first an open car. That was a silly move which put the project back a bit. The coupe was much more effective, of course with the classic coda tronca of the clipped tail 1300. This time the model name meant “Giulia Tubolare Zagato” with no reference to the Kamm tail. It made the Salons in 1962 but the TZ1 would not race until October of 1963.

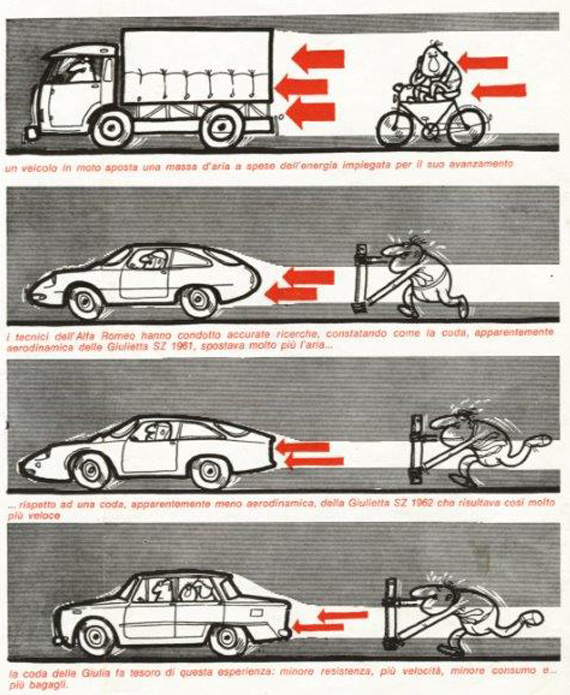

In the meantime, back at the factory, Orazio Satta’s team was working on the replacement for the 1300 sedan. And Satta, having graduated as an aeronautical engineer, was setting up tests in a wind tunnel. Sometime in the course of 1961, out pops this strange new four door sedan, with a very pronounced Kamm tail, just like the Zagato Coda Tronca. And it worked–the 1600 Giulia sedan was praised for its low wind noise and aerodynamic efficiencies. We have not been able to find concrete evidence that Satta was influenced by the Coda Tronca, but the coincidence is more than remarkable and the company played up on the coincidence.

Everybody’s got one

There can be no doubt that both Ferrari and Maserati were keenly aware of the success of Zagato’s clipped tail design at Monza in mid-1961. Yet, even today, little or no credit is given to Spada and Zagato for the successful deployment of the Kamm tail. The Ferrari GTO is most often quoted as an early race car application. However the GTO was being developed by Bizzarini in the summer of 1961, and even by September, the GTO mule still had a rear end much like that of the SWB Ferrari. It was not until the winter of 1961 that Scaglietti developed the design into what we know of the GTO, with a Kamm-like tail.

Insofar as Maserati, one might think of the famous Tipo 60 as having a clipped tail, but such a design was not actually implemented until 1962, with the decidedly sharply cut tail Tipo 151.

To be sure, From then on, most race cars and many production cars would incorporate some sort of Kamm tail. The 2600 Zagato, the Zagato Jr, the Alfa Sud, the new Giulietta, the Milano…and of course the Kamm tail Spider, putting a Zagato motif on a Pininfarina classic. Note that the positive effects of the clipped tail are only witnessed at high speeds; most production car uses of the Kamm tail were stylistic efforts only. The essence of the Kamm theory is that a sharply cut tail will ‘fool’ the wind into thinking that the shape actually has a long tail.

The use of the Kamm tail, along with spoilers and wings, heralded the arrival of serious aerodynamic studies as applied to the race car; wind tunnels became more widely available and essential to design. Race car design would now be a science. The Kamm tail was highly effective on most racing car designs well into the 1970s. However, the truncated tail is just a small part of lowering the cd value which in itself is a complex formula.

It’s interesting to see how a little tin snipping at the Zagato shop resulted in an important achievement, and why, therefore, the Lopresto find is of interest. But what car did Lopresto find, and what is its history? Tune in next week.

*Gijsbert-Paul Berk adds: “Reinhard had no formal academic credentials and lacked the possibilities to verify his theories and Dr. Kamm who worked for the FKFS institute (Forschungsinstitut für Kraftfahrwesen und Fahrzeugmotoren Stuttgart) had them. So for a small sum of money Koening-Fachsenfeld transferred his patent rights to the FKFS and Kamm became responsible for the development of the K tail. Thus, what often is called a Kamm tail could also be called a Koening-Fachsenfeld tail.”

Aerodynamics be damned. I still think the round tail (Coda Tonda) SZ is a much nicer looking car. Having had two, I may be biased.

Oliver

Very interesting story indeed! But why not mention Carlo Chiti’s Shark-Nose FERRARIs 156 F1, 250 TR and 206 SP displaying a “coda tronca”from the beginning of the 1961 season? And is it true that the rear spoiler was suggested to Chiti by former aircraft engineer Ritchie Ginther to prevent his car from taking off in the Curva Grande during early test session in Monza?

A fascinating period it was, with both costly errors and dramatic designs.

I’ll be looking forward to the next article!

No mention of Dr Kamm’s postwar career at Stevens Institute of Technology where he worked in the towing tank facility. Never met or talked to the gentleman, but remember his tank model of a Loewy Studebaker coupe modified with his Kamm tail. As I recall a real car was so modified and performed very well at Bonneville! At low sub-mach speeds air can be considered non-compressible, and many interesting designs were tested in the “tanks.” As a honors lab project, I was testing a sailboat hull, the storage area held many interesting models from sea planes to submarines.

I owned one of Oliver’s round tails (00147) for many years. I raced it, rallied it and, finally, fully restored it prior to selling it on. Unfortunately, I have learned that since then it was consumed in a fire. It was a wonderful car and gave me great joy to own and drive. I have also owned a Coda Tronca for more than 30 years and it has given me great pleasure as well. Regardless of which aesthetic you prefer, all Alfa SZs are delightful cars to drive, especially when used as they were intended.

Andy

voir mon précédent mail

Andy that is a shame. Very sorry to hear that. I also had a lot of fun with it in my early days of vintage racing (first PVGP etc). I wonder if someone recreated it with the Chassis number. Also wonder what happened to 062 that went to England.

Oliver

Oliver / Andy,

Would love to have had the experience of owning one of the older SZs. Unfortunately, I don’t think my financial assets will permit expansion of my Alfa Zagato collection beyond the Jr. Z and SZ (ES-30).

Remember that the early GTO’s had bolt on Kamm spoilers on the tail. This was a likely afterthought in the beginning. The ’63 cars had the spoilers incorporated into the bodywork. Prior to remote wings on race cars we had ‘Gurney flips’ which was the same sort of device just pop-riveted on to the tails of whatever you were running. I think the idea was that with a flip-up the air didn’t spill off the back of the tail into such a draggy vortex and hence increased top speed. I seem to remember these flips appearing on SZ’s and even the Coda Tronca’s late into the ’60’s in races at the ‘Ring and the Targa. The beautiful SWB tail treatment would look terrible with a Kamm tail as would the even more beautiful late model SVZ. Good work Lopresto discovering this v tasty machine and showing us the body ‘in its own juice’.

Thanks to the Loprestos for showing the car in raw aluminum. Now that there are so few craftsmen who can do this work, it is very interesting for those who see it in person to be able to see see the body joins that give a clue how it was built; I wish more concours would have a “bare metal” class where cars in restoration could be entered.

Looks like faded white paint, not raw aluminum. Frankly it looks too good for raw aluminum. In the bare metal, you’d see a chaotic welded patchwork of hand-hammered panels, which varied from one side to the other. Zagato was far better regarded for their design and their weight reduction than their craftsmanship.