By Brandy Elitch

Dieppe is a small French port on the English Channel, more famous for its scallops than for its links to the automobile industry (although pre-WWI, the French Grand Prix was held there).

But from 1955 until 1994, Dieppe was home to a constructor whose cars are revered in their home country the same way that the Corvette is revered in the US: the Alpine.

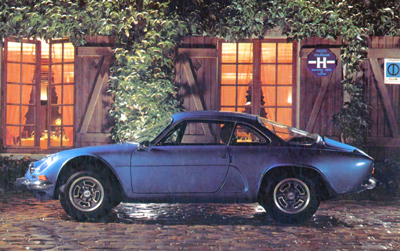

The Alpine A110

It would not be too farfetched to compare Alpine’s founder, Jean Redele, with the father of the Corvette, Zora Arkus-Duntov. Redele’s father was one of the first Renault agents in the post WWII period, after the death of Louis Renault, when the company decided to build a small car for the masses, the 4 cv. Jean modified the 4 cv to become a competitive rally car, and in 1953 Renault approached him to prepare five cars for the Mille Miglia. From then on, Redele based all of his designs on Renault drivetrains, and his cars were sold and serviced by factory Renault dealers. By 1968, Alpine had been allocated the entire competition budget for Renault, and two years later Renault took over a majority of Alpine. Later on, Renault bought engine tuner Gordini and merged it with Alpine, to form Renault Sport, and this led to a win at LeMans in 1978, and ultimately to the technology which propelled Renault very successfully into the world of Formula One. None of this would have been possible without Jean Redele. Even today, all Renault Sport cars are manufactured in Dieppe, where the famous Alpine “arrow†can still be seen on the side of the plant.

The following images are from an Alpine sales brochure, kindly provided to us by Francois De LaCloche.

In the same year that Renault approached Redele about managing their rally effort, Zora Arkus Duntov wrote a letter to Ed Cole, head of Engineering at GM, to offer his ideas on how the Corvette could be made into a better car. On the strength of his unsolicited letter, Zora was invited to come to Detroit, and the rest is history. There is even a French parallel, because Zora joined the French Air Force in 1939 and fought with the French through 1940. Both men spearheaded the development of a sports car within the bureaucracy of a huge car company (think of the challenges that this must have posed to them!), and both men succeeded in creating a legend amongst their own countrymen. Not to stretch the parallel too far, but I think a case could be made for calling the Alpine the “French Corvette”.

Courtesy Francois De LaCloche.

Just like the Corvette raided the GM parts bin for many of their component parts, Redele used standard Renault components for the Alpine. He chose the word “Alpine†because his favorite motoring experience was driving his highly modified 4 cv in mountain rallies, particularly the Coupe des Alpes. The early versions were based on the 4 cv and later the Dauphine, but the A 110 is based on the Renault 8 and the 16. One version of the A 108 was styled by Michelotti, and Redele (I think) took his inspiration for the A 110 couple from this model. The A 110 debuted in 1962. About 7500 cars were made in Dieppe, and another 2500 under license in Spain, Mexico, Brazil, and Bulgaria, of all places. The car had a steel backbone chassis, including the front suspension cross-member and a rear bridge for mounting the motor, transmission, and rear suspension, bonded to a rigid fiberglass bodyshell (another Corvette similarity). It used a coil spring suspension with double wishbones in the front, and a swing axle in the rear with the driveshafts running inside of the axle tubes, aided by four wheel disc brakes. From 1962 until the end in 1977, there were fully thirteen variants of the A 110. Once the car adopted the aluminum block motor from the Renault 16 TS, with two Weber 45’s (generating 125 DIN HP and a top speed of 130 mph) it became a serious rally contender, ultimately winning the granddaddy of all, the Monte Carlo Rally, in 1971, and in 1973, the World Rally Championship for Makes. Redele was one of the first people to realize the power of using special competition parts from a large factory to meet the homologation demands of the FIA (just like Marshall Teague did with Hudson back in the early 1950’s!).

Courtesy Francois De LaCloche.

After fifteen years of production, the A 110 was superseded by other models, which were more on the order of sporting grand touring cars than out and out racers. They are of course collectible too, but not to the same people. The Dieppe factory was later used to make what is to me the ultimate small car/rocket ship: the R5 Turbo, a worthy successor to the A 110. Today, every car museum in France has it’s a 110.

Courtesy Francois De LaCloche.

It is truly the iconic French high performance car of the 1960’s and 1970’s, and, like Matra, a great source of national pride for the French. It would appear that hardly any Alpines ever made their way into the States, unfortunately for us. It wasn’t until last September, on a drive from Paris to Torino to attend the Lancia Centenary, that I got to ride in one. My friend Francois suggested that we spend the night in Burgundy with his cousin and her husband, who, as it turned out, had developed an Alpine A 110 for track racing, similar to what we do with historic racing here. I guess I should have been a little suspicious when he told me to put a helmet on. We fired up the beast, and spitting and snarling, we headed out into the very rural countryside of Burgundy, where the traffic on the roads consisted mostly of large tractors. I can tell you that my host drove at what I would consider to be nine-tenths, taking up most of the road, but never breaking the rear end loose. I kept wondering what would happen if we came across another car, but since this was around 6 pm, I think all the farmers were home having dinner, as the roads were deserted. We blasted through small farm villages with no one in sight, the roar of the motor echoing from the stone walls all around. I came away with a newfound respect for the A 110, plus a grin from ear to ear.