During the month of May and the Indy 500, it’s appropriate to think about two events, Monaco and the Indy 500. Most of us are probably very aware of the appearance at Indy of Alberto Ascari in 1952 and the broken wheel which ended his drive. However, more obscure are the other Ferrari entries that continued for some years after the 1952 event. Below Roberto Motta puts it all together in two parts with the help of images from the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum. [Ed.]

By Roberto Motta

Photos courtesy Indianapolis Motor Speedway

Ferraris attempts at “The Brickyard” began in 1952, but continued in subsequent years until 1956, with the last Ferrari Bardhal Experimental car. The results were never encouraging, partly because of a lack of preparation and commitment. Perhaps Ferrari did not take the unique and difficult requirements racing at the Indy 500 as seriously as was warranted.

The Origins of the Ferrari Indy Car

It all began well, with a powerful, race-winning Grand Prix car. The 375 F1, originally designed, developed and built to beat the Alfa Romeo Formula 1 World Championship used the big block Lampredi unsupercharged engine to compete with Alfa’s 1500cc supercharged straight eight. Initially, Lampredi created a 12-cylinder engine of 3322 cc and 300 hp, which became known as the 275 F1. However, in order to compete with increasingly fierce competition and seeking more power, the displacement was increased gradually to reach the 4102 cc and called the 340 F1. At the end of the ’50 season, the latest evolution of the 12-cylinder Lampredi engine was now up to 4493.734 cc with a of bore and stroke of 80 x 74.5 mm, keeping the design philosophy of the V12 of the 275 F1. In its latest evolution the substantial increase in capacity increased the power to 350 hp at 7000 rpm.

The new engine was initially mounted in the chassis of the 340 F1, which was revised to improve stability by means of new suspension and dual cylinder brakes. Subsequently, it was installed on a new car called the 375 F1, and presented for the first time in August 1950, during tests at the Monza track. A few weeks later, the car debuted in competition at the GP of Italy, but the cars driven by Ascari and Serafini were forced to retire.

During the following season, the 375 proved increasingly effective. On July 14, 1951 at Silverstone, the 375 F1 # 12 driven by the Argentinian Froilan Gonzalez entered history as the first Ferrari to win an official World Championship F1 event (begun in 1950).

The American adventure begins

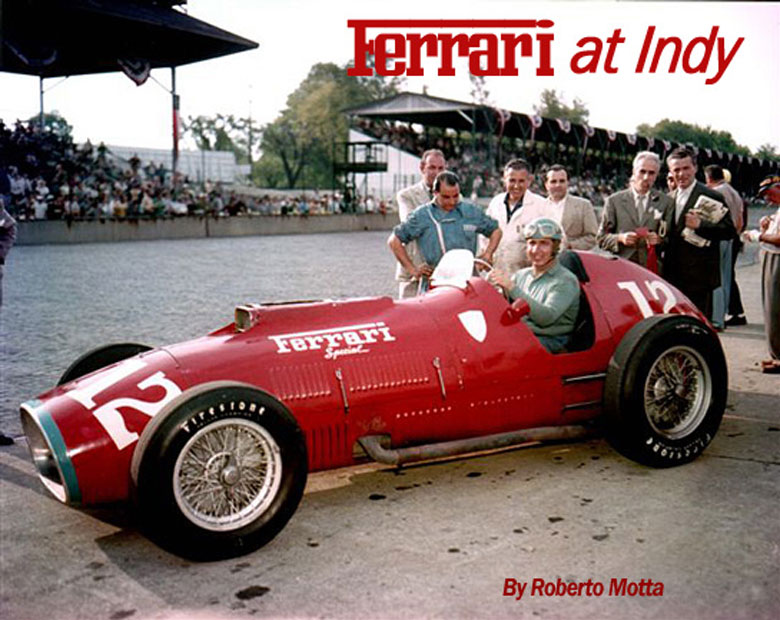

Ascari poses for the cameras at Indy. He was all for the attempt at the Brickyard. He would become World Champion in 1952 and 1953 driving for Ferrari.

This famous car would be the same one that ventured forth to America to try its hand at the famous Indianapolis 500 in 1952. In a way it made sense, as at the time Indy was on the FIA calendar as points scoring event; a win there would help Ferrari garner points for the F1 world championship.

The European teams were aware that to be competitive in the Indy 500 it was necessary to create a car with completely different technical choices to the ones used in European racing because of the nature of the American circuit. The Europeans also knew that it would be risky to not only their reputation but to the cars themselves as they could easily be written off against that famous wall.

At the same time, the F1 formula was changed to 2 liters and the 375 F1 was suddenly obsolete. This change encouraged Ferrari to enter a car under the name “Ferrari Special” via Ferrari distributor Luigi Chinetti.

It is undeniable that participation in the 500 could be an excellent form of advertising for the expansion and development of a commercial network to support sales of cars in the U.S. Finally, Alberto Ascari urged Ferrari to compete in Indianapolis on May 30, preferring to give up the first race of the ’52 F1 Championship, the GP of Switzerland to be held on the 18th of that month. The cast was set; a try at Indianapolis seemed inevitable.

Suddenly there were four

Over the winter of 1951-52, the Indy program progressed rapidly. In short order there were four Ferraris scheduled to race at Indianapolis. While Chinetti entered the chassis number 1 car for Ascari, Chinetti and/or Ferrari sold three more to American teams. According to Stan Nowak writing in Cavallino, one of the big 4.5 cars had already been sold off to Tony Vandervell and became the “Thinwall Special”.

Three 375 F1 cars were raced at the Grand Prix of Valentino in Turin on April 6th in an open F1 event and driven by Farina, Ascari and Villoresi, complete with the high hood intake scoops. All retired but Villoresi, who won the race. Obviously, these were the now out-of-date team cars or conversely, the new 375 Indys. Since work had been going on through the winter on the Indy versions, we can assume that Turin was a test race for the cars. By May they were all on their way to new owners in the U.S; Nowak notes however, that the Farina car was crashed at Turin and was not able to be repaired in time for Indy. There may have been as many as eight 375 Ferraris but that is speculation. We do know that aside from the Ascari car, three more were made ready for Indy and sold. Money talks and here is who paid:

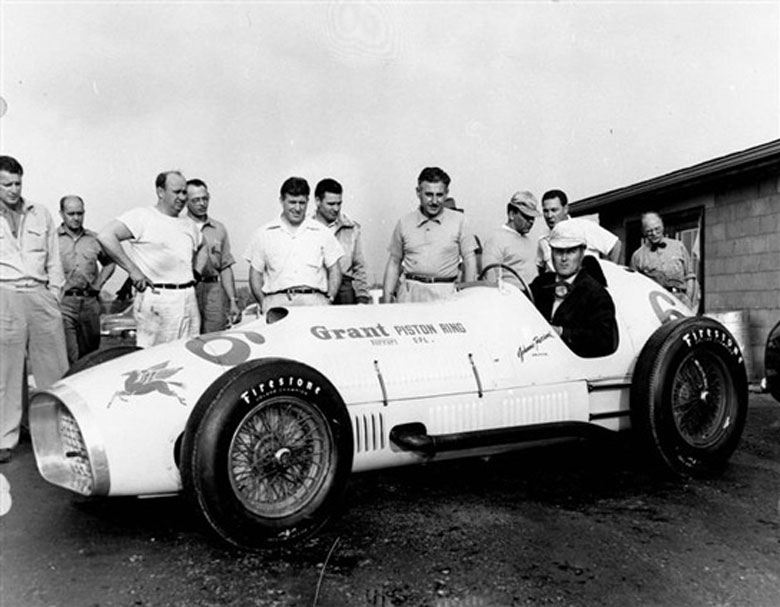

Chassis number 2, given the number 6 for the 500. Sponsored by Grant Piston Ring, and purchased by Mr. Grant to be driven by Johnnie Parsons. Over the winter, Grant visited Maranello and suggested adding a wraparound windshield to the car. It appeared at Indy with a standard windscreen as well.

Chassis number 3, with number 35 in qualifying, was purchased by Johnny Mauro and sponsored by Kennedy Tank.

Chassis number 4 was No. 38, labeled as the Howard Keck Special sponsored by Mobil Oil, was given to Bobby Ball drive.

No doubt this was a windfall for the Ferrari factory, but the scattered effort, development and support meant that none of the cars would succeed.

Changes to the Ascari 375 F1 car

These figures can be assumed in the case of the Ascari entry; changes to the other three cars may have been different. Compared to 375 F1, the chassis was extensively modified and the wheelbase increased from the original 2320 mm to 2450 mm. The frame was strengthened and the total weight went up to 829 kg.

The Pirelli tires normally used on the F1 car were replaced with more suitable tires supplied by Firestone and mounted on spoked Borrani wheels, in front were 17″ wheels and 18″ wheels in the rear.

The body of the car was that of the F1, with the exception of the area of the air intake on the top of the hood.

It was necessary to reduce the bore of the engine from 80 mm to 79 mm, for a total of 4382.093 cc or 258 CI per Indy rules.

The engine used a 2 valve per cylinder head, magneto ignition and two spark plugs per cylinder with a battery of double-choke 46 mm Weber carburetors

With a compression ratio increased from 11:1 in the original 375 F1, to 13:1 in the Indy version, the revs increased from 7000 rpm to 7500 rpm and the Indy was able to deliver 400 hp. But would that be enough for Indy?

Unfortunately the gearbox remained the original 4-speed mounted in unit with the ZF limited slip differential. It proved to be a handicap because the other Indy cars had only two gears and no shifting once underway.

The Grant car arrived early at Indy but already Parsons is unhappy with the Ferrari. He would opt not to drive it and the Grant car was never officially entered in the race. Courtesy Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

Arrival and testing

In early May, a small group of Ferrari employees left for Indiana. The group included Ascari, Ugolini, mechanics Meazza and Reggiani, engineers Aurelio Lampredi and Luigi Bazzi, and the sports journalist Giovanni Canestrini.

The Ferrari Indy 375 Ascari, given number 12 for the race, came out on the track with ‘Ferrari Special’ painted on both sides of the hood. Eager for success, the team began testing the 375 Indy.

But soon it was reported unsuitable to the needs of the American race; too heavy and not very fast. Furthermore, Ascari was forced to make use of the gears along the oval at Indianapolis with the result of losing precious time. From the start the daily telephone reports to Enzo Ferrari reported a degree of pessimism.

Qualifying and the race

Nevertheless, on May 10, Ascari passed the “rookie test” impressing the Indy officials. At that time, the test required that the driver had to do four rounds of qualifying with very consistent times.

During the tests, the Indy Ferrari was plagued by various problems. When Walt Faulkner tried the Parsons car , after a few laps he came in shaking his head and saying to the mechanics, “If this is the monster Ferrari, load it on the ship and send it back home. It has no chance of victory.”

One of the problems which plagued the 375 of Ascari was the use of three two-barrel Webers which limited low-end torque.

A set of three four-barrel Weber carburetors were sent urgently as checked baggage, but the package ended up in St. Louis and reached Indy just in time for qualification runs.

Finally, on May 24, the Indy 375 managed four laps at an average of 134.308 mph, placing Ascari 19th overall among the 33 cars on the grid. At least one Ferrari would be on the starting lineup of the 1952 Indianapolis 500.

On 30 May, race day, the stands were packed to capacity with colorful and festive crowds who warmly welcomed the drivers competing to win. Ascari was aware that he would not be able to fight for the victory because the carbs were still not right. After the start, the Ferrari kept the pace and by the tenth lap was in eleventh place, climbed to eighth and dropped back to ninth. After 40 laps, the spokes of the rear wheel gave way in the North Curve. Ascari spun and got the Ferrari down into the infield. He was not hurt. Over 40 laps, he had averaged 128.714 miles per hour (207.1 km / h).

Americans had sportingly advised the Ferrari engineers to switch to Halibrand alloy wheels, better suited to bear the burden of the Indy turns, but the Italians did not follow up. Needless to say, after the wheel failure, Enzo Ferrari took the matter up with Borrani in no uncertain terms. The failure also resulted in the use of the three-ear knock off hub vs. the traditional two ears.

Quick Status on the four Indy Ferraris:

Chassis number 1, the Ascari car. It of course retired in the 1952 event but came back to Indy in 1954 and had a very adventurous life, eventually ending up with Chinetti Jr. Current whereabouts?

Chassis number 2, the Grant Piston Ring car given the number 6 for the 500 never did qualify. Parsons got it up to 132.5 mph in practice before he bailed out. No one else wanted to drive it either. Today this car is owned by a Washington D.C. collector.

Chassis number 3, with number 35 for Johnny Mauro was never able to reach the speed needed to qualify, even with Ascari up. It seems that Mauro had purchased in anticipation of its use in the famous race up Pike’s Peak. It is in the Indy Museum today.

Chassis number 4 was No. 38, a Howard Keck Special sponsored by Mobil Oil for Bobby Ball. In the tests, the mechanic team of Frank Coon and Jim Travers changed the power of the engine Ferrari by installing a Hilborn mechanical injection system but it too, failed to obtain the desired result. The car was fast enough to qualify for the race, however, doing 134.4 mph. According to Nowak, Keck withdrew the car without reason and put it in a warehouse where it stayed for the next 35 years! Eventually it ended up in a collection in Long Island, current whereabouts unknown by us. Readers?

Sources

Cavallino #46: The Indy Ferraris by Stan Nowak

Road & Track, September 1952: Ferraris at Indy

Ferrari Automobili 1947-1952: Millanta, Orsini, Zagari Editoriale Olimpia

Part II will address the Bardahl and 250/I Ferrari.

Very interesting article. Too bad Ferrari failed to grasp the highly specialized nature of high-speed American oval racing. A trace of snobbery, perhaps?

Also, I think you mean “Bardahl,” not “Bardhal.”

Wonderful to have Roberto’s attention to this great story. A couple of points:

The reason so many American teams bought Ferraris was that they had been blown off by the Ferraris in the Mexican Carrera late the previous year. Great advertising!

The Indy entry was not an official Ferrari effort. It was a quasi-private entry headed by engineer Aurelio Lampredi with the enthusiastic support of Ascari.

Contrary to the tenor of the article, it was a serious attempt with every chance of success as explained in my Haynes biography of Alberto Ascari, which needless to say I recommend to anyone interested in this race. The Ferrari qualified without the ‘pop’ used in fuels by the Indy regulars, so it could race at its qualifying speed. The Italians planned much faster pit stops that would have given them an advantage. In spite of a cautious start Ascari was averaging 128.71 mph when he retired; the race-winning speed was 128.92 mph. He would have been right in the hunt for victory.

True, Lampredi saw the three-eared knock-offs at Indy and they soon appeared on his Grand Prix cars, starting a trend that swept the European F1 cars.

Roberto Motta and the Editor both thank Karl for his comments, particularly in reference to Troy Ruttman’s winning average speed. To be sure, Ascari may have done very well had the car lasted!

Roberto is doing a very good job. There are only some minor passages which aren’t 100% correct:

1. The 375 Indys were built new from scratch in 1952 on a new Gilco frame. Roberto correctly mentions the lengthening of the wheelbase. There were only two such cars, to be driven by Ascari and Parsons. (I’m not 100% sure that he did actuallly drive it instead of a refurbished 1951 model, like the other two entered).

2. Indy record mentions Ferrari as official entrant.

3. Lampredi came to Indy at a later date, together with Canestrini.

I did extensive researches on the subject (a long article was published in Ruoteclassiche magazine some 10 years ago. Another one at a more recent date). Looking also at photos not in the Indy archives it is decently reasonable to say that the Borrani wheel collapse was a consequence of the spin and not the trigger. Photos from the outside of the track show clearly that, after the spin, the wheel is still undamaged. Furthermore, you cannot push rearward so easily a car with a rear wheel badly damaged. A sensible driver like Ascari would have noticed the incoming collapse of the wheel before it eventually happened.

My opinion, also found in some contemporary articles, is that the joint or some other part of the rear right halfshaft/diff seized, due to overstress. That may explain the sudden spin, quite unusual if due to the collapse of the wheel.

Furthermore, why Ascari didn’t go on for the remaing few hundreds meters to reach the pits? It could have done it with a partially collapsed wheel. On the contrary, he knew that with a seized halfshaft it was nonsense.

Then, there is another likely explanation: he never wanted to race on Friday, and that Memorial Day was a Friday. He probably also knew well that red was an unlucky colour at Indy. All that carried on an unbearable burden on him and he choose to give up.

The photo of the destroyed wheel, taken after the race, is non-consistent with the photos of the accident. As usual with the Ferrari Team, it was a post-facto explanation to be presented to Enzo Ferrari to absolve the people in charge of any sin or mistake.

About the wheel: the use of cast wheel was an obvious non-sense because suspensions and the entire car were set up for the lighter wire wheels. It was a wise decision by the Ferrari people not to mount them despite the unrequested counsel by the locals.

Sorry to have been so long, yet the story is fascinating and plagued by factoids, not facts. Thanks, Roberto, to have resurfaced it.

glad to see an article like this, before I was only aware of Maserati racing at Indy.

I have two questions:

1.)Did the author ever hear that around 1963 when Ford was dickering to buy out Ferrari that one of the sticking points was that Enzo Ferrari wanted to be able to run at Indy and didn’t want Shelby or Ford running their cars there if he chose to run Ferrari cars there?

2.)Way back around 1954 when Shelby was first driving for John Edgar, he drove in the Mt. Equinox Hill Climb and won in a car I have heard described as a Grand Prix car and also has a Indy car. Was it made for Grand Prix but later tried at Indy?

Finally I remember at a Barrett jackson auction seeing a red Ferrari single seater that might have been a Ferrari Indy car but I read somewhere that the auction company repainted it and lost all the original patina (and probably lettering for the sponsor).That must have been a bargain because I bet few of the auction goers ever knew Ferraris had been raced at Indy…

Again I refer readers to my Ascari biography.

It is ludicrous to suggest that Ascari simply gave up. As well to suggest that red was an unlucky colour at Indy. Ridiculous!

Ascari was looking forward very much to racing in the 500. Lampredi said thyat after his retirement he stayed in the pits for the rest of the race not saying a word, so disappointed was he at not finishing a race that both of them saw as winnable.

You can see the Johnny Mauro 375 Indy at this year’s Ault Park Concours d’Elegance in Cincinnati, OH on Sunday, June 10th courtesy of the Indianapolis Speedway Museum.

GREAT EXCELLENT §

Excellent coverage of this articlemmuch appreciated!1

I started following “Ferrari” in the early fifties, reading a lot of sports car mags long gone, and one article I remember was on Tony Vandervill and the “thin wall bearing” Ferrari attributed his success too. Ferrari got the steel for his cranks from the U.S. and he studied the “bearing” as the heart of the Ferrari. One article I recall (it has been ages ago) was that the clearance between the crank and the bearings was off just a bit and that made the engine “tight”. It never wound up as a Ferrari should. Then there was the enigmatic relationship between Ferrari and Luigi Chinetti. I think it was an in and out affair. When Luigi told Ferrari his cars were “winning in America”, he said something like, ”I don’t care.”

My father went to Indy each year back then and the front engine off set Meyer Drake, Offenhauser mill was king. This was large four cylinder which no one could beat. It was the heart of the championship car. Another problem was that Ferrari hung on and hung on to tradition. He believed in carburetion, was loyal to the Italians, which meant Weber, did not go to disc brakes when they became available, and he stuck with Borrani wire wheels. The G.T.O. sported Borranis.

I think Michael Parks who brought fuel Injection to Ferrari’s attention. While they were one-hundred- thirty-mile an hour cars, they could have done more with a different transmission, but Ferrari was a lot like Abraham Lincoln. If he believed in a case he fought for it tooth and nail, if he didn’t, he just went along with the flow. I think down deep he was a sports racing person who thought the Grand Prix brought out the best in cornering, and “Indy” was just not a true test of “roadability”. He believed that the ultimate true test of a car was that it had to handle all surfaces and turns and not four monotonous corners, and the “brickyard” wasn’t it. The Indy crowd didn’t like it. That was the rumor. That culminated in the Monza Indianapolis machine which they had to weld the flywheel onto.

Ferrari had his world view, and he was true to himself.

He went from shoeing mules during WWI to the pinnacle of success. He basically went it alone.

Does anyone know what fuel brand was used in the Ascari Indy car in 1952? Thank you…