Story and photos by Rick Carey

This article originally appeared in VeloceToday in 2003 and again in 2018. Due to the many requests we had to see this article after the series on the B.A.T.s as published last week, we thought it might be nice to give everyone a chance to read it again without a premium subscription.

I’ve always admired the work of Franco Scaglione. Anyone who could create the B.A.T.s on the tall-engined Alfa 1900 chassis, who displayed such sympathy for airflow and was willing to challenge convention with shape and curve rather than embellishment and accoutrement, was an exceptional talent. And full credit also to Nuccio Bertone who gave Scaglione free rein to reinvent extravagantly.

The appearance of the three B.A.T.s at a Blackhawk auction years ago in Danville, California was a landmark event. In person they were even more impressive than in photographs. Creative details abounded throughout the coachwork and they were pleasing and intriguing from every view. The B.A.T.s are extravagant and exaggerated, to be sure, but their physical presence also is organically whole and, as their name, Berlina aerodinamica technica, suggests, intuitively sympathetic to minimizing their movement through the air and to managing skillfully the fluid they must displace in their passage.

But their numbering continued to chafe at my numeric sensibilities. Why did Bertone and Scaglione begin at 5? With the succeeding B.A.T.s numbered 7 and 9 the odd-numbered progression of the series was apparent. Why was there no B.A.T. 1 or B.A.T. 3?

I had no idea that resolution of that gap was in the offing a few weeks ago when Miles Morris, head of Christie’s International Motor Car Department, called. “We have a car in your area that we may consign to our New York auction in June. It’s been in a garage for thirty years. Would you be willing to go over, put some air in the tires and push it outside to take some photos for the catalog?” he asked. Being a sucker for barn-finds, “willing” was not an issue. “I’ll call you when the papers are signed,” Miles concluded.

A few days later he called back with the go-ahead and more information. “It’s a Fiat-Abarth with a one-off Bertone body that was displayed at the 1952 Turin Motor Show. Designed by Franco Scaglione and sold to Packard.” The hairs on the back of my neck went up. With Miles on the phone I grabbed Luciano Greggio’s “Bertone – 90 Years” [procured through Veloce Press] and flipped open the Catalogo volume to discover faded period photos of an extraordinary aerodynamic exercise with a history that ended in 1952!

I didn’t sleep much that night, anticipating the discovery that was in store for the morning.

The next day, a cold and nasty New England spring morning, the neighbor watching the house opened the center door of a three-car garage only 3 miles as the crow flies from my home. The gently curved tail of the Bertone Abarth was closest to the door, adorned by

small subtly-shaped inward-curving fins that showed unmistakable evidence of the fertile creativity of Franco Scaglione, the craftsmanship of Bertone’s artisans and the germ of the concept that would mature into B.A.T. 5 only a year later.

We aired up the tires, took some photos in place, ascertained that the brakes were tight and closed up the garage to await better weather and some extra hands to attempt to move her out for a few more shots.

The Abarth 1500 Biposto

Abarth’s speed equipment business was already growing rapidly and the Cisitalia-based race cars of Squadra Carlo Abarth were becoming uncompetitive. Abarth needed a new headline-grabber to promote the business and at that moment Fiat introduced a new line, the Fiat 1400, with a short stroke overhead valve 4-cylinder engine and unit chassis. Carlo Abarth, having run through the Cisitalia cars and parts which became his in lieu of severance pay when Piero Dusio decamped to Argentina after the debacle of the Porsche-designed Cisitalia Grand Prix car, seized upon this engine and drivetrain for the first complete Abarth car. A welded-up platform chassis was designed and Abarth breathed upon the Fiat 1400, boring it out to nearly 1.5 liters and fitting a Abarth intake manifold with a pair of Weber Tipo 36 carburetors and 4-into-2 tubing headers to develop a reported 75 horsepower. Its chassis number is 214-01, indicating a type designation of 214 which is oddly out of sequence with the rest of Abarth’s chassis numbers.

Bertone took the order to clothe Abarth’s 1500. Nuccio Bertone had only recently discovered Franco Scaglione and the Abarth project became Scaglione’s first for Bertone. Unveiled at the 1952 Turin Motor Show the Abarth Biposto was a sensation and received widespread coverage in the media. John de Boer has found photos in journals as diverse as L’Auto Accessorio and Road & Track, even a page in Motor Trend suggesting ways to incorporate the Biposto’s details in customizing Studebakers, Ramblers, Hudsons and Henry Js.

The Abarth Biposto and Packard

Packard sent one of its 24th Series 1952 Packards to the Turin show along with Bill Graves and Edward Macauley, respectively Packard’s Engineering V.P. and chief designer. The Italians were mystified by the Packard’s bulk but Graves and Macauley, grasping at straws to help keep the foundering Packard afloat and breathe some life into Packard’s stodgy styling, selected the best example of Italian design they could find in Turin to take home to Detroit: the Abarth Biposto.

At that point the trail of the Biposto, so widely publicized and praised, began to disappear.

Even the interior was in remarkable and original condition, and a bit more futuristic than other Italian interiors of the era.

Richard Austin Smith’s Abarth 1500 Biposto

While Graves and Macauley were in Turin Packard announced a new President, James C. Nance, brought in from a successful stint running GE’s Hotpoint appliance business. GE was a management development laboratory long before Jack Welsh emerged from the pack and Nance was one of its stars, a consumer marketing expert with a superstar track record. Fortune magazine dispatched an associate editor, Richard Austin Smith, to Detroit to profile Nance and his plans to resuscitate Packard. His visit coincided with the Abarth Biposto’s in-house display and his subsequent article, “Packard’s Road Back” in the November 1952 issue, included a column on the experiences of Graves and Macauley in Turin and the Abarth Biposto. A photo showed the bemused Nance inspecting it and the caption concluded, “Its value is now largely ornamental; under Nance, Packard styling will stick to lines that are ‘architecturally correct,’ forgo the lunar asparagus.”

It’s impossible not to observe that Packard might have stood a better chance of survival with more of Scaglione’s “lunar asparagus” and less of Nance’s architectural correctness, an essential difference between home appliance design and auto design.

During the visit Smith suggested several slogans for a new Packard advertising program which were later adopted and Nance, admitting he had no use for the Abarth, gave it to Smith in July 1953 as token compensation for his suggestions.

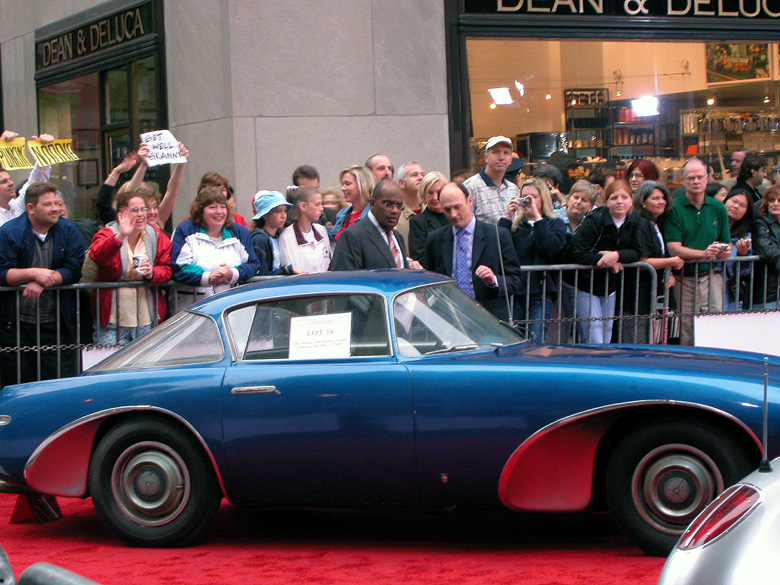

It was actively if sparingly used by Smith for the next twenty years, accumulating an indicated 31,926 kilometers. His two sons fondly remember the impression it made when their dad arrived in it to pick them up at school. Eventually Smith retired from Fortune to a restored 18th century farmhouse in Groton, Connecticut and the Abarth Biposto went into its garage where it sat, unused, but to judge from its condition not neglected, since at least 1977, the date of the last registration in its glovebox. Its last public appearance was in the early Sixties when the sons recall it being displayed along with two other cars at the entrance to the New York Auto Show. For nearly a half century its existence was apparently completely unknown to auto historians and collectors.

Is the Abarth 1500 Biposto “B.A.T. 1?”

It has my vote, and also that of Nick Georgano’s Coachbuilding volume of “The Beaulieu Encyclopædia of the Automobile” where it is mentioned as “the coupé he [Scaglione] had designed on a Fiat-Abarth chassis in 1952 [which] led directly to the BAT 5, BAT 7, and BAT 9 series of streamlined prototypes….”

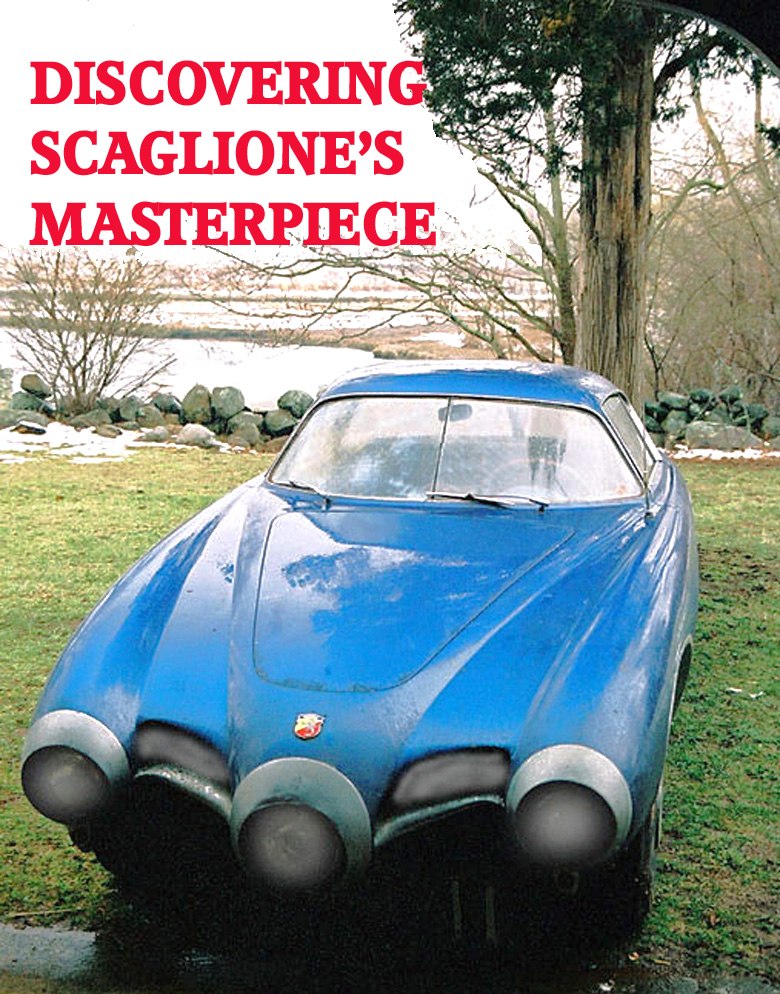

The triple element nose, subtly-shaped fins, split windshield and rear window and thin greenhouse posts all were picked up, accentuated and refined in B.A.T. 5, 7 and 9. In one respect the Abarth 1500 Biposto is superior to later B.A.T.s: its short stroke Fiat 1400 engine allowed Scaglione and Bertone to create a much lower car than the Alfa 1900-based B.A.T.s. It is loaded with neat details like the front marker lights and taillights recessed into the fenders in tubes. The interior is fully trimmed and instrumented and its service over twenty years with Richard Smith demonstrates that it was much, much more than a throwaway show car, even though it was based on a one-off chassis and drivetrain.

In remarkably good and original condition, only an aged repaint in slightly darker metallic blue separates Dick Smith’s Abarth 1500 Biposto from its configuration at Bertone’s 1952 Turin Motor Show display.

What of “B.A.T. 3”? Greggio’s Bertone Catalogo depicts a Fiat 1100-based aerodynamic Bertone coupé exhibiting many of the concepts embodied in the Biposto and subsequent B.A.T.s, but its history is undefined. My bet is that it will fall neatly into the design and time gap between the 1952 Turin Show Abarth 1500 Biposto and the 1953 Turin Show B.A.T. 5.

Time and auction catalog deadlines ran out before New England’s weather improved so we went back to Dick Smith’s garage in a cold drizzle, edged the recalcitrant Abarth out onto the slippery lawn and shot it as best the circumstances (and the tree right outside the garage) permitted. The Biposto is back inside now, waiting for Intercity to take her to Rockefeller Center for the auction on June 5.

I’ve slept better since. I’ve seen and touched this remarkable barn-find, admired its details and the skill and craftsmanship that went into its conception, design and construction. I’ve marveled at its preservation and followed the thread of its fifty years with Richard Austin Smith. And, to my own satisfaction, I’ve filled in at least the first of the missing numbers in the sequence of B.A.T. Berlina aerodinamica technica.

1952 Abarth 1500 Biposto coupé

Coachwork by Bertone, Design by Franco Scaglione

Chassis number 214-01

Engine number 101.000 * 032083

It was a shame it wasn’t used as a concept. Truth be told in 1954 it would have been risque for Packard to try it. I have seen those exhaust exits used before, I think on a Hudson Italia? It turned out nicely. Seems marketing won out over passion on the use of what was likely B.A.T. numero uno.

Good to see # 1 back! Jaime I

Wow what a cool story, even after all of these years.