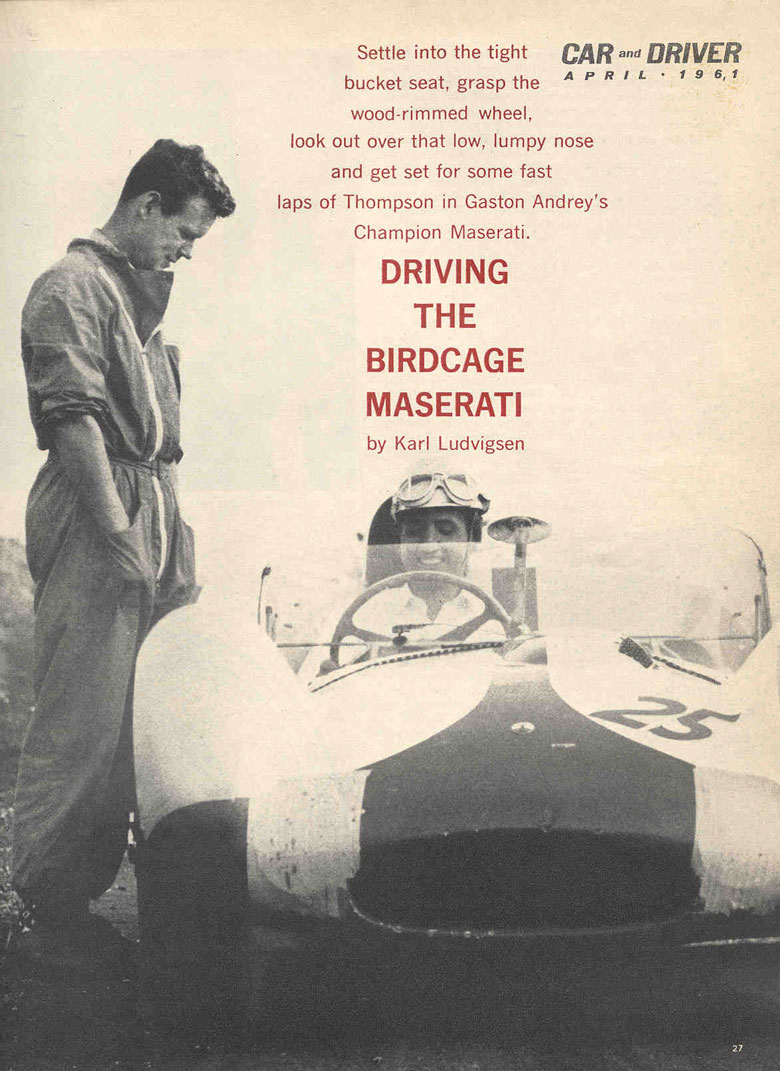

What was it like to drive a Birdcage in 1961? Below, Karl Ludvigsen graphically describes the feel, the noise, and the technique of driving the Magnificent Front Engined Birdcage. This article, originally published in the April 1961 issue of “Car and Driver”, has been republished here with his express permission. Originally published in VeloceToday November 2014.

By Karl Ludvigsen

When you click home the ignition key on the sketchy dash of a Birdcage, a strong red light burns deep within the broad, thumb-sized starter button. To me that light became a symbol of the vast power lurking with this apparently ramshackle piece of machinery, like glowing coals in the crater of a slumbering volcano.

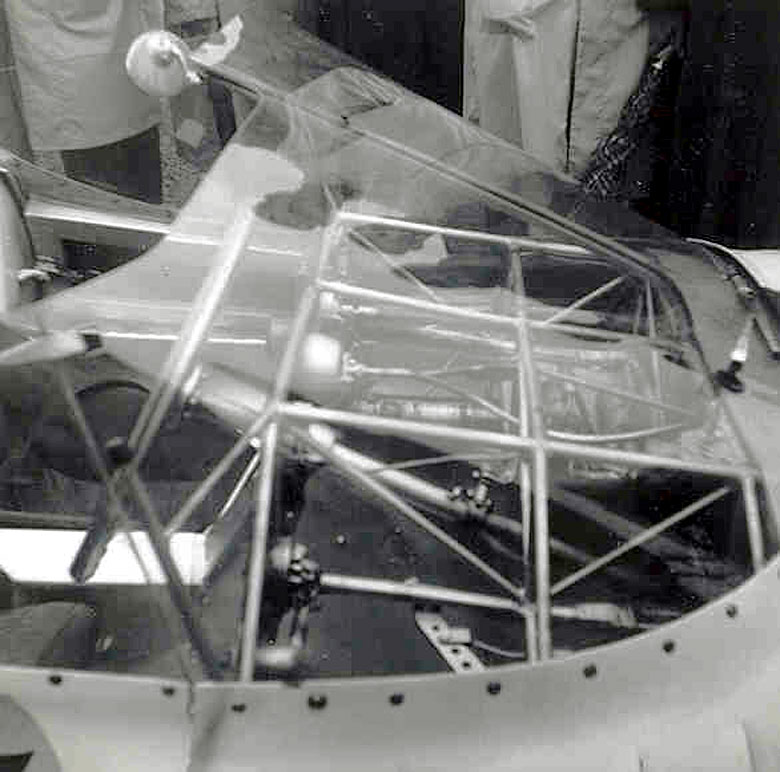

If you’re not already familiar with the Maserati Tipo 61, better known as the Birdcage, be informed by a glance a the accompanying cutaway or at the Tech Report in SCI, April 1960. Its designer, Ing. Alfieri, broke with all the Italian traditions of chassis design and trimmed to a remarkable minimum, a step made possible bit the increasing significance of short, smooth course American races and the decreasing stature of great sports car classics like the Mille Miglia and Tourist Trophy. Only the Targa Florio remains to separate the Birdcages and Lotus Nineteens from real road going automobiles.

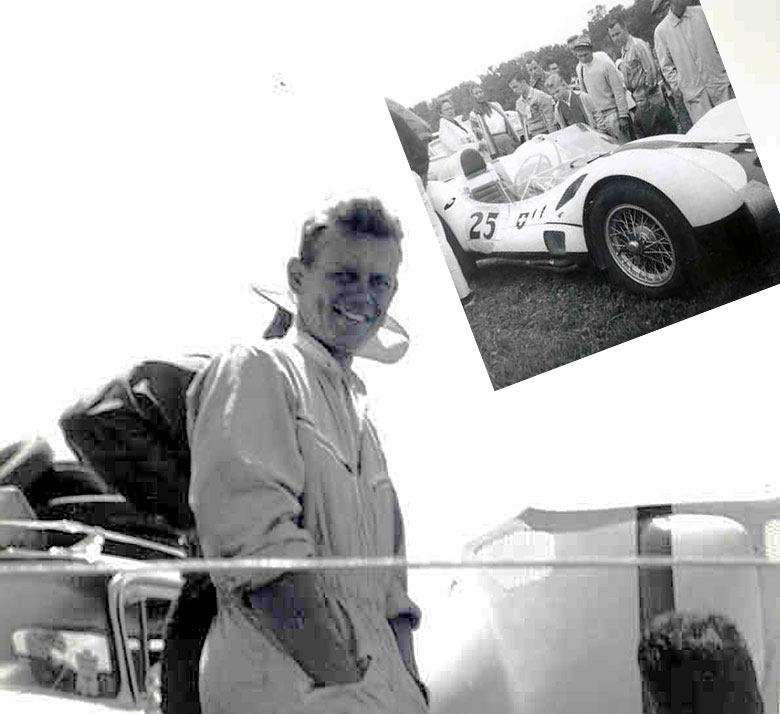

This particular Birdcage is one of the very first to reach the U.S., bought by Mike Garber for Gaston Andrey to drive at Nassau and in SCCA competition. It’s been very successful in both areas. In the car’s first race at Nassau in 1959 Gaston felt in command immediately, being nerfed off into the shrubbery during a duel for second. Last year took third in the Bahamas against year-younger equipment, and did well enough against Walt Hansgen’s slightly hotter ‘Cage to win the SCCA Class D Modified championship. The New York Times’ Frank Blunk judged wisely in awarding his Sports Car Driver of the Year trophy jointly to Gaston Andrey and Bob Holbert. Certainly we’re talking about one of the most consistently competitive Birdcages in the country.

Luckily the weather was magnificent the day Irv Dolin and I met the Andrey crew at George Weaver’s Thompson Raceway, in the far northeastern corner of Connecticut. Mechanic Osky Feldman had already warmed up the machine, and Mike Garber had turned a few laps. Then George Weaver, Maserati enthusiast of long standing, tried the Birdcage and came in with some interesting reactions: “After driving my big V8, ‘Poison Lil’, for so long, I was very impressed by the easy, light handling of my more recent 4CLT. It made ‘Lil’ fell like a real truck. Now, after driving the Birdcage, I feel the same way about the 4CLT!”

Naturally I was anxious to find out for myself. Gaston finds the swing-up driver’s door superfluous, but I used the contraption to avoid smashing the Plexiglas. Lowering myself into the bucket seat, I found that it fits tight and firm. There’s no upholstery on it worth mentioning except perhaps the thickness of the red plastic covering, which is none too luxuriant. You sit low, right on the floor in fact, or as close to it as the narrow seat sides will let you. Reaching out, I found the steering wheel in just the right position. It’s a reassuring wheel, small in size with the usual finely-crafted spokes but with a heavy wood rim deeply notched on its underside to provide a sure grip. It’s a wheel you can really grasp.

Gaston had already relocated the seat back as far as it would go, and tilted it slightly rearwards, but leg room was still tight for me. I don’t know how Shelby, Gurney, Jeffords and Hall drive these cars—but I can see why Bill Krause felt right at home! Clutch and brake pedals are quickly located, though my big feet got tangled at first with the “dead pedal”, on the left, and the steering column. The throttle pedal has a long, light travel. The gear lever is placed low on the right, very close up to the seat, working in a compact gate with a flip-up latch for reverse. Everything duly noted, I switched on the ignition and observed with satisfaction the evil glow within the starter button.

The engine started quickly at a poke of the button and half-throttle. First gear, for getaway only, was selected by pressing down on the lever and pulling it back into the first notch. Not surprisingly, I stalled the machine at first try at the clutch—being very leery throughout the test of overstressing the fragile gearbox—but got it away cleanly the second time. “Cleanly” is the word, too, for the Birdcage feels amazingly light as you pull away. Just a touch of the throttle seems to whisk it swiftly along.

Once set in motion, the Maserati loses its loose, glued-together feel. It becomes a densely solid, single chunk of mechanism set low and steady on the ground. My eye level let me look just over the top of the windshield, down over the drooping hood with its exciting bulges for wheels and carburetors. Driving the car I was never aware of the open network of tubes behind the dash that seems so naked and disturbing to the onlooker.

Andrey’s car at Road America, June 19, 1960. Everyone wanted a shot of the \’Cages\’s Cage. Photo by Don Vack

Most startling of all was the noise. Not the expected bellow from the exhaust, but the shrieking and wailing of the driveshaft and gearbox which crowd so close to your left arm and back. At first in neutral there’s a whir from the shaft, then as you pull away the car is drowned in a roaring gear whine from the cog box that seems to fill the inside of the Maser. At low speeds it almost completely drowns out the exhaust noise and seems to promise instant destruction. Once the revs are up and the car is flying you’re mainly conscious of the deep, throaty roar from the big, megaphoned pipe that ends just under the driver’s door.

This big, four cylinder engine has a wide range of power without the “peaky” feel so often encountered in recent Maseratis. Below 2500 rpm it won’t take full throttle, coughing and stuttering if you try, but from there on up it comes in smoothly and strongly. I didn’t take it over about 6200, while Gaston usually does 6500 and presses on to 7000 if he needs it. He finds that in serious competition against the likes of Hansgen and Holbert he can’t let the revs drop below 4000. Since the gearing is such that on many tight courses the tach would normally fall to 2500 in second, his lowest usable gear, Gaston has to slide the tail violently to keep the wheels spinning at appropriate revs around many hairpins!

Not wanting to sample the wheelspin technique, I just enjoyed the delicious, backslamming power coming out of corners and plunging down straights. It’s power aplenty for a car this weight, but not the kind that’s embarrassing if you’re too heavy on the throttle. Traction at the de Dion rear is the biting, geared-to-the-road variety that just propels the ‘Cage’ forward. The impression isn’t of chained violence as with the Bocar, for example, but of a perfect balance of power and chassis with one goal: covering the ground.

Solid and not too heavy, the clutch was excellent. The transmission was even better. It’s hard to believe that a mechanism for changing gears that looks so fundamental could be such sheer delight to manipulate. The constant mesh spur gears are engaged by face-type dog clutches, made as shallow as possible during the most recent redesign of the box. If you don’t have the relative revs just right when you essay engagement of these dogs, you can feel it in the shift lever—gently, not harshly—and you can feel just how much you’re off by the frequency with which the lever quivers. If the speeds are right or nearly so, the gear goes in with such uncanny ease and speed you would swear the little lever was linked only to thin air! In many ways the Birdcage works better the faster you go; this is one of those ways. You need to get into the rhythm of very fast driving before the shifts consistently click home right. When they do it’s a beautiful feeling—and lightening fast. It literally could not be any faster.

All the while I was discovering that the disc brakes are strong and highly progressive in a way that calls for plenty of leg muscle in competition. Though Thompson calls for a lot of braking, I didn’t use them very hard that afternoon. I also found that the ride is hard and the seat is harder. My admiration and sympathy go out to the Andreys, Gurneys and Mosses who have driven these cars hard for long distances over trying courses. It may not be the “rocketing buckboard” that Griff Borgeson found the K3 Magnette last month, but it’s certainly the 1961 equivalent. The Maserati felt flat as a plank on the road at all times, a literal “flying shingle” in the Ken Miles tradition.

Handling was completely stable, immensely so on the straight. I tried flicking the steering wheel sharply to one side at speed, as we usually do on C/D test cars, and the Maser snapped back to its straight ahead path at once without the slightest tendency to deviate. It understeers basically, accented on tight corners by its high polar moment of inertia, but this can of course be balanced by proper use of the throttle and by appropriate tire compounds and pressures. Gaston likes to set the car up so the front end’s understeer just matches the rear end’s drift as it comes out of the medium-to-fast corners on full throttle. The means the whole car drifts gently across from the apex to the outside under power, remaining pointed straight down the road all the while. For more outward drift you press down and for less you back off, but there’s never any rear end breakaway or the like. The Maserati just slides inexorably outward.

On tight corners the story is naturally different. You have to slide the tail around under power, both for speed and for the rev range reason mentioned above, and there’s ample power to do it. It’s a completely controllable maneuver but somehow not an efficient one, and I suspect that the Porsches score here. Light and with a nice feel of the road, the rack and pinion steering gives you the speed and response this kind of cornering demands. Altogether I guess I drove the Birdcage about 35 miles—miles that went by much, much too fast.

Afterward Gaston, Osky, Irv and I talked over the mechanics of preparing and maintaining the Type 61. For tires they fit Firestones at the back, either soft or hard compound depending on the situation, and the “stickier” Dunlops or Pirellis at the front. They adjust the tire pressures over a 34-38 psi range, from a starting point of 36, according to the demands of the course. Du Pont’s Telar is used in the cooling system, and SAE 50 Oilzum is found in the oil tank. Though 90 is suggested, the crew has learned from experience to use the 140 weight oil in the gearbox, or even 240 for long races. The plugs are Lodge RL49, RL 50, or RL51, depending on the race and the weather.

Cars like these are obtained from Rallye Motors, in Glen Cove, Long Island, and the Maserati Representatives in Beverly Hills, California. The price is a remarkably cheap $10,500 at the factory, which comes to about $12,000 when duty’s paid and the car’s air-landed here. It’s a special bargain when matched against the $16-17,000 being charged for a Lotus Nineteen! Over twenty Type 61s have been built, enough to keep Maserati winning around the globe.

Andrey looks happy with the car. Inset, future VeloceToday editor inspects the famous Maserati frame (ok, he’s the short one). Photos by Don Vack

Osky and Gaston expected a brand new Birdcage to require minimum maintenance, at least for the first season; they found that this wasn’t the case. About the only things that haven’t given trouble, in fact, are the clutch and the Girling design brakes. The frame, and the way it behaves, reminded me of a wire-spoked wheel; when it’s whole, it’s very solid; when one spoke breaks you don’t know it but it leads to progressive breakage of the surrounding spokes in an evilly unobtrusive manner. It’s just that way with the lacework of tiny tubes in this “soda straw special.” Osky has been hard put to keep up with all the welds in this frame, but at least he knows where to look now when the car starts acting queasy under heavy braking. Vigilance of this kind is a small price to pay for a car that performs so dramatically, excitingly well when it’s right. Maserati’s trying to top it, though; don’t miss the rear-engined Type 63 Birdcage on the following pages.

Postscript

The Andrey/Garber T61 was serial number 61.2455. The history of the car since 1961 was put together by Willem Oosthoek in the book “The Magnificent Front-Engined Birdcages”

For sale, 1961, $10,000

NY Auto Show, April 1961.

Sold to Julius Byles in 1962 and was driven from Long Island to Florida with Irv Dolin. The trip was described in the October 1962 issue of Car and Driver.

To Joel Finn

To Peter Livanos

To Harley Cluxton

To Bob Baker, who drove it at Monterey six times from 1991 to 1996.

Current owner Dan Davis.

a literal “flying shingle” in the Ken Miles tradition…what a great quote…….

Lovely, these cars were one off, a brilliant, if “off the wall” concept from Afieri, never will we see their like again.

It’s a great shame that most of them, end up in “collections” to make money, rather than being used for what they were built for …. racing!