Story and photos by Paul Wilson

The most satisfying part of any restoration is the last stage: putting sparkling new pieces onto a gleaming car. Minimal effort, maximum reward. After a few minutes’ work, you can stand back and take deep breaths, enjoying a visual feast. That’s part of it, anyway. But there’s another side. You discover how many parts a car really has, and how much time it takes to deal with mundane matters nobody thinks much about.

As my roadster nears completion, I’ve had both the pleasures and the pains.

As soon as the car arrived back from the paint shop I eagerly put on the taillights, glued in the trunk seals, and installed the fuel filler. It looked fantastic.

Then I started on the interior. That’s just a matter of cutting panels to size, gluing on material, and screwing them in place–right? I’d already made flanges to screw to. But it’s never that easy.

Covering the awkward side areas behind the seats and the shut posts with smooth, simple panels was a challenge.

An even bigger job was the doors, where a complex curved top section wouldn’t match the flat lower part. But that was a blessing in disguise…

…prompting me to put a strip of bright trim where the top and bottom panels meet. Perfect for the period, and more exciting than a plain door.

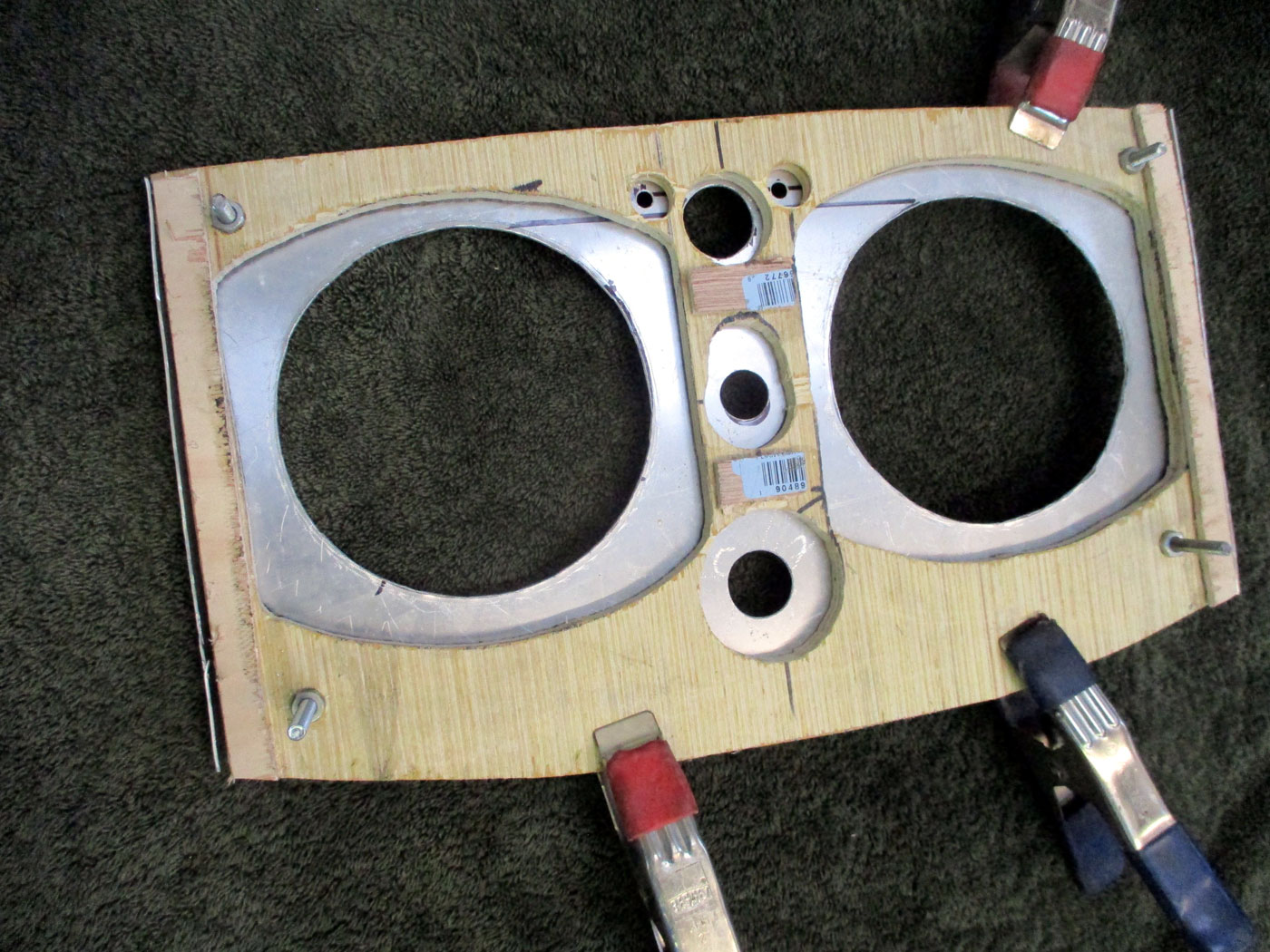

But the central instrument panel was harder. Even though I had a complete set of correct 6C2500 parts–two big gauges, a turn switch, a starter push, an ignition key that doubles as a light switch, and two warning lights–each attaches differently.

Some have inner and outer rings that tighten on sheet metal, some are made to countersink in a wood dash of different thicknesses. I made the basic form from plywood, put on a metal front skin.

Working on the interior, at the end of every day I could stand back and look at something beautiful. But then I got into difficult jobs that gave no such rewards. First I had to make a floor–and before that, something to rest it on. The X-frame left a big open space.

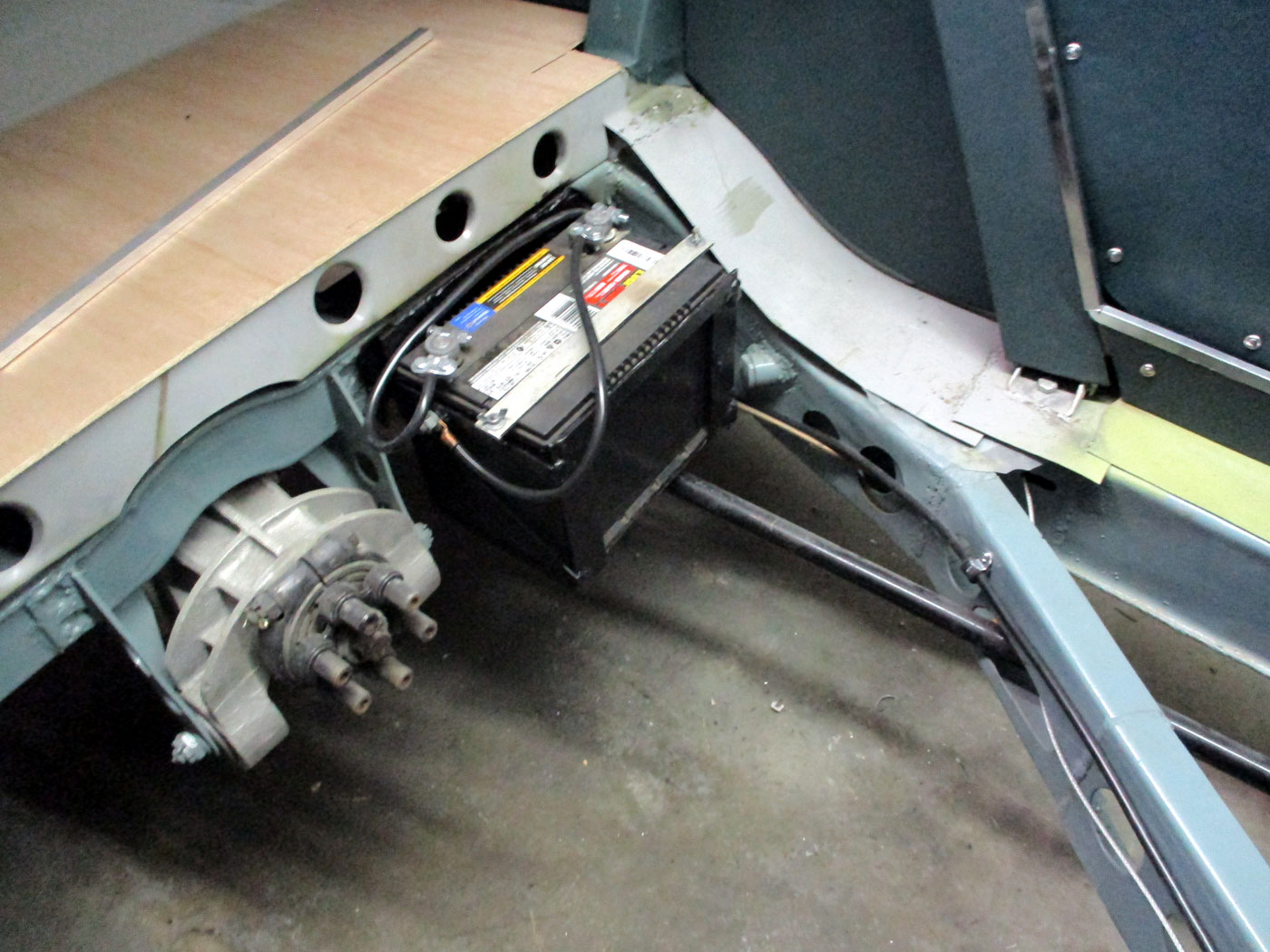

The position of the original battery box, tucked behind the passenger seat, was OK except the battery was smaller. So I made a new battery box.

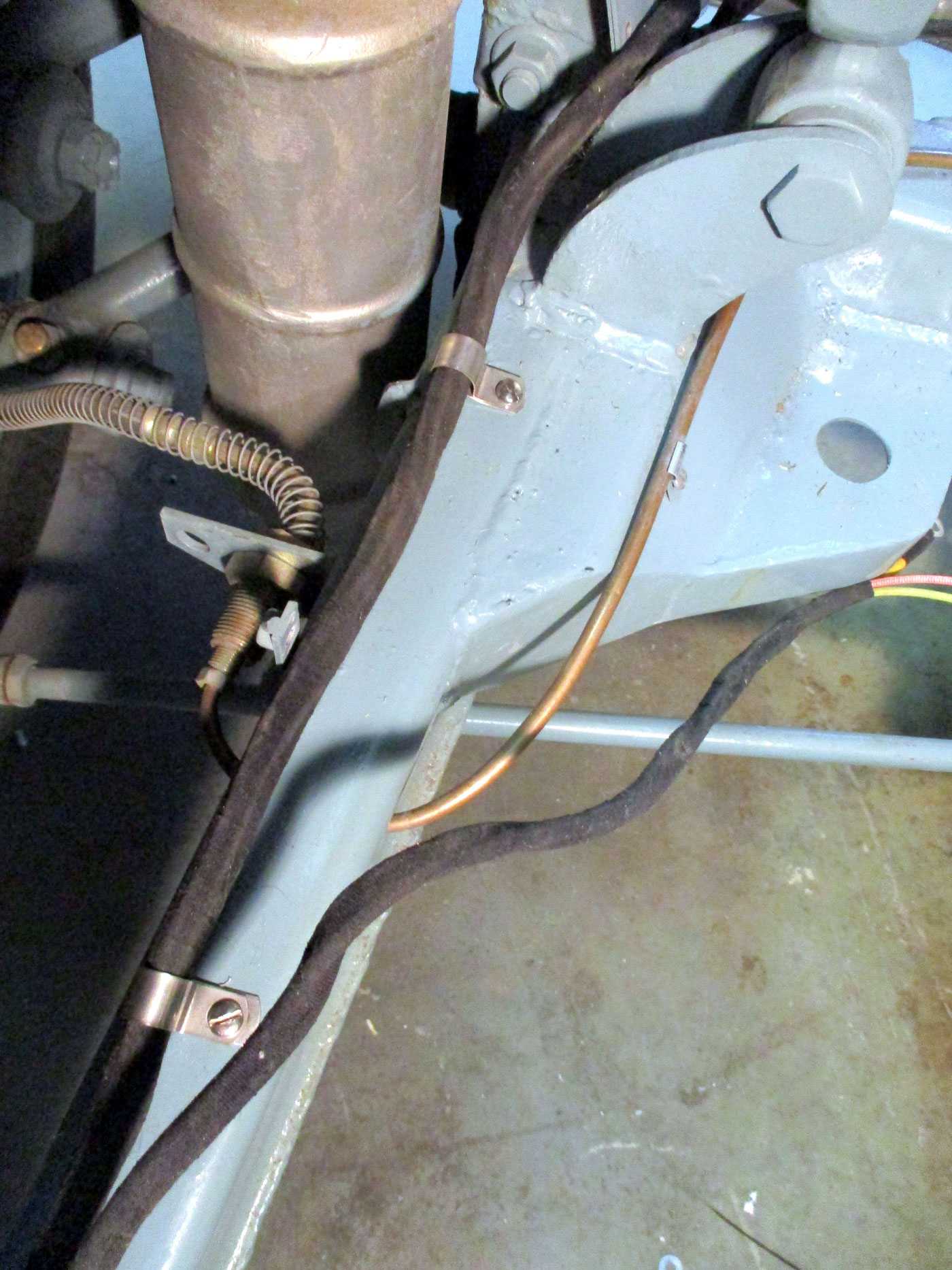

Period roadsters such as my XK120 had plywood floors, which works fine on flat areas. Metal is needed for the tunnel and transmission hump, and also for the upward curve behind the seats. I made patterns with paper…

I wanted to take off the transmission cover without removing the floorboards, for example, so it had to sit on top. A panel near the pedals allows easy access to the master cylinder. A tidy cover attached with two wing nuts fits over the battery.

I’ve said that this work was merely functional, aesthetically unrewarding. But those clean black floors and bright aluminum were so pretty that I hated to cover them with the felt that goes under carpet.

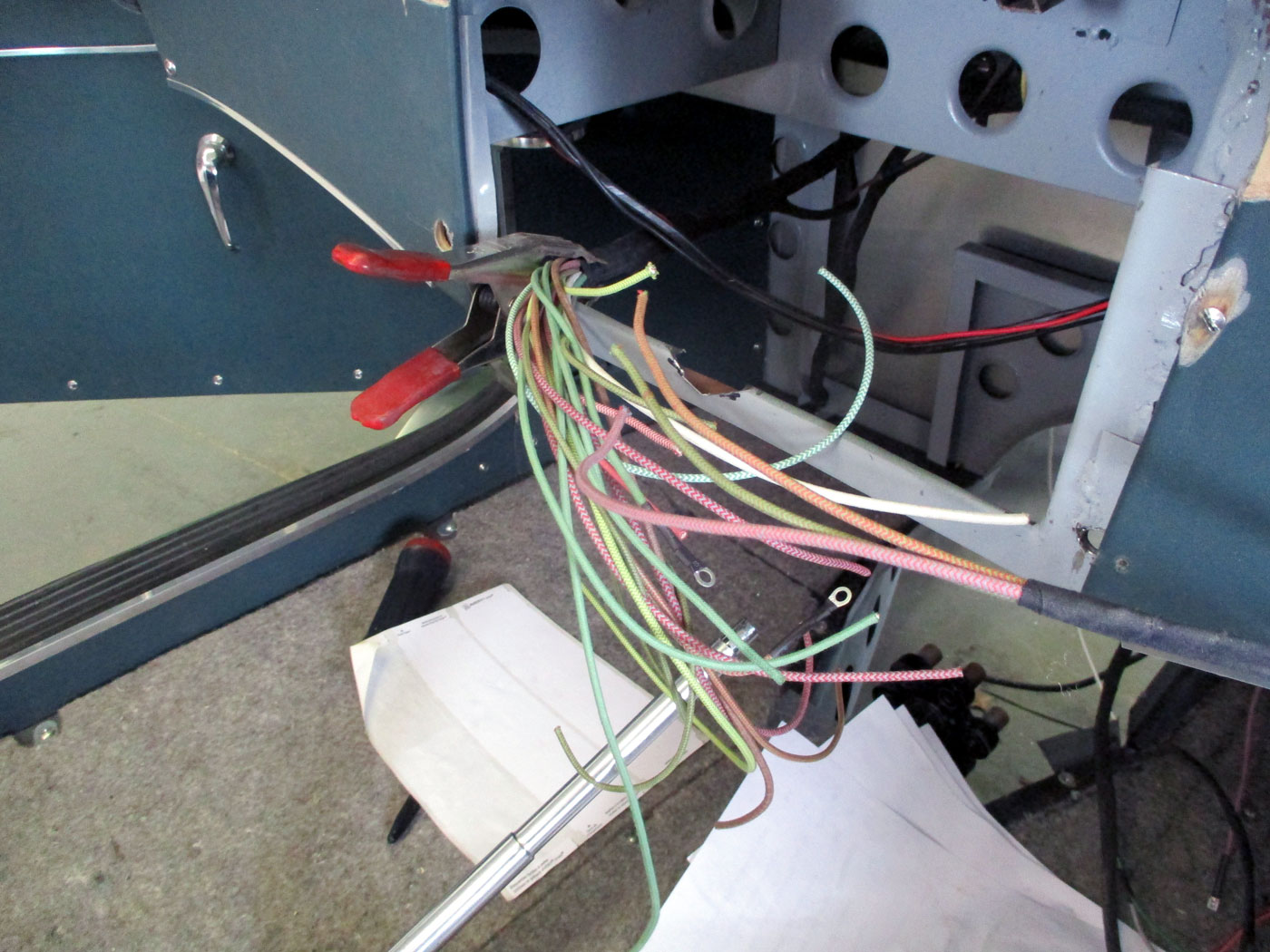

The wiring harness was another huge, thankless challenge. There’s no such thing as an off-the-shelf 6C2500 wiring harness. So I had to design my own from first principles. Some stuff only works when the ignition is on, other things don’t. Each circuit needs a fuse. The brake lights use the same wire as the rear turn signals, which is coordinated by an eight-terminal relay. On a huge poster board, I drew lines between the components, from which I made a list of individual wires and their endpoints. There are lots of wires–45 different color codes, not counting black ground wires.

As I ran individual wires, lying on my back with aching neck muscles, huge tangles accumulated at the dash, the fuse boxes, and the firewall box. Their color codes should have clarified things: blue with white to the high beams, for example. But most of the period-correct wires looked more or less the same. Is this a green/yellow, or a green/red? They all seemed a sort of a muddy brownish-green. Many times I found myself gazing at this mess, my mind a blank, having short-circuited some minutes before.

In the end, I got everything working. Many hours with a circuit tester finally paid off. And while wiring gives no visual reward, seeing the headlights go on, or hearing the horn, are moments of triumph after such an ordeal.

In high school we learned about asymptotes: ½, 1/4, 1/8, 1/16 . . . Each step gets closer to zero. But when does it reach zero? Actually, never. I’ve finally realized that restoring a car is like this. Every day I do something that makes it more complete. It’s almost finished. Almost . . .

And all the earlier chapters of the Wilson 6C Roadster:

Read Part 1

Read Part 2

Read Part 3

Read Part 4

Read Part 5

Read Part 6

Read Part 7

Congratulations Paul, on a great job.

A thing of beauty !!! Joe Wilson

Hand building from scratch! What an impossible project, yet mastered by time, skill and good sense. Congratulations Paul, nearing the end, what an inspiration!

Beautiful craftsmanship in your restoration. Where do you intend to show your 6C ? I’d like to see it –

I hope you kept a circuit diagram with wire colors noted for all of your re-wiring. That’s something done with each car I wire, and it saves monumental time when there are later maintenance problems.

Congratulations on a job well done ! Absolutely beautiful !

what did you use for the dash board cover and the door panels. I have 1939 citroen Light 15 and it has very thin leather like material– most modern materials are very thick. Thanks

Hi Mike Andrews,

I used high-quality vinyl stuff that’s indistinguishable (by me, anyway) from leather, and of course a tiny fraction of the cost. I wish I could give you the name but a brief search failed to turn it up. Sorry!

Paul

Hi Arthur Weinman,

I’ll take the cars to a few shows when they’re done. But I can’t finish them because of delays from my suppliers. For the roadster, the engine has been off for three years, and a steering wheel promised two years ago hasn’t yet arrived. For the coupe I’m waiting for a transmission adapter (two years). Extremely frustrating! I bug these people regularly, but they’re immovable. I’ve done everything I can with what’s here. Either car could be finished up in a couple of months if I had what’s missing.

Because of this roadblock on the 6Cs, I’ve started another exciting Alfa project. You’ll read about it by and by in VT.

Paul