By Pete Vack

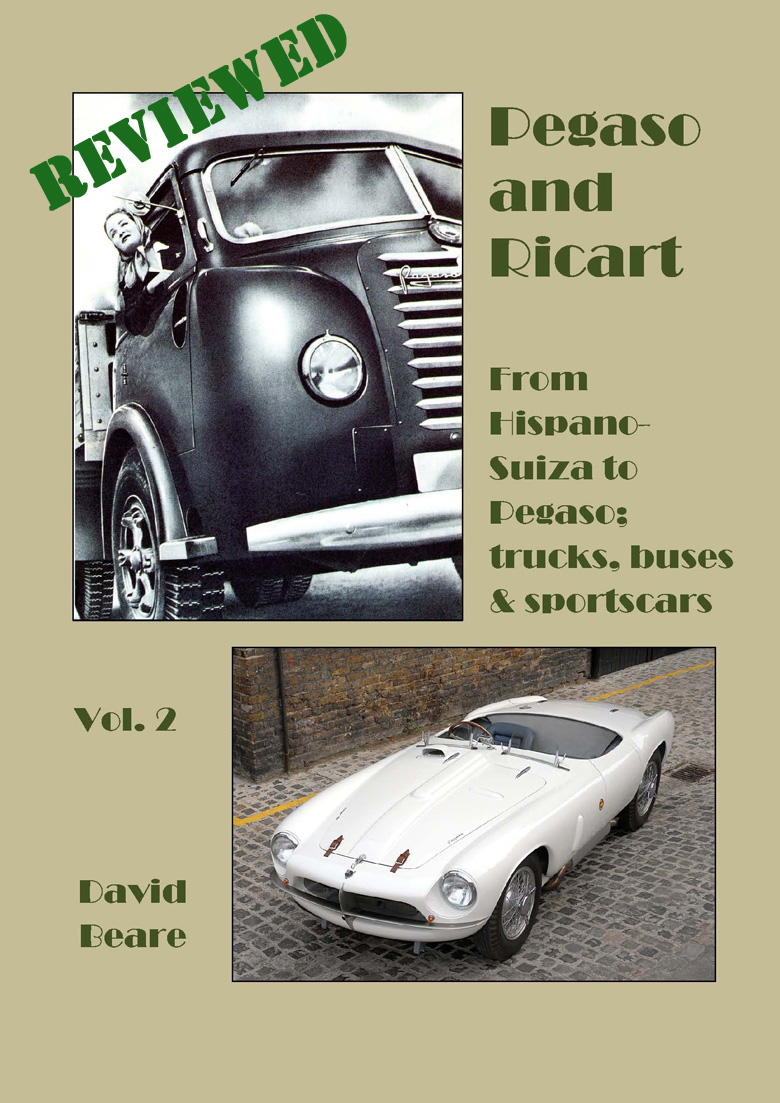

Last week we reviewed Volume 1 of David Beare’s two part look at Hispano-Suiza and Pegaso, which took us from the establishment of Hispano-Suiza in 1904 to the takeover by the Spanish government in 1946 and the establishment of a new, totally Spanish firm to produce a line of trucks based on the work of Marc Birkigt. Enter Wifredo Ricart (b. 1897) and the car that would be called Pegaso. (read Beare’s article). Volume 2 is Pegaso and Ricart From Hispano-Suiza to Pegaso: trucks, busses and sportscars.

A previous article written by Griff Borgeson for Automobile Quarterly about Ricart addressed only his years with Alfa. But as Beare relates, Ricart had a very interesting life before Alfa and Pegaso, and by the age of 22 with Francisco Pérez, he was designing and building race cars with a four cylinder DOHC sixteen valve 1498cc engine! He later established his own firm and then Ricart-España before the Depression and moving on to Alfa Romeo in 1936.

The crash of Marinoni. Although badly burned, the car does not look to be rear engined as was the Ricart 512 prototype. Centro Storico Alfa Romeo

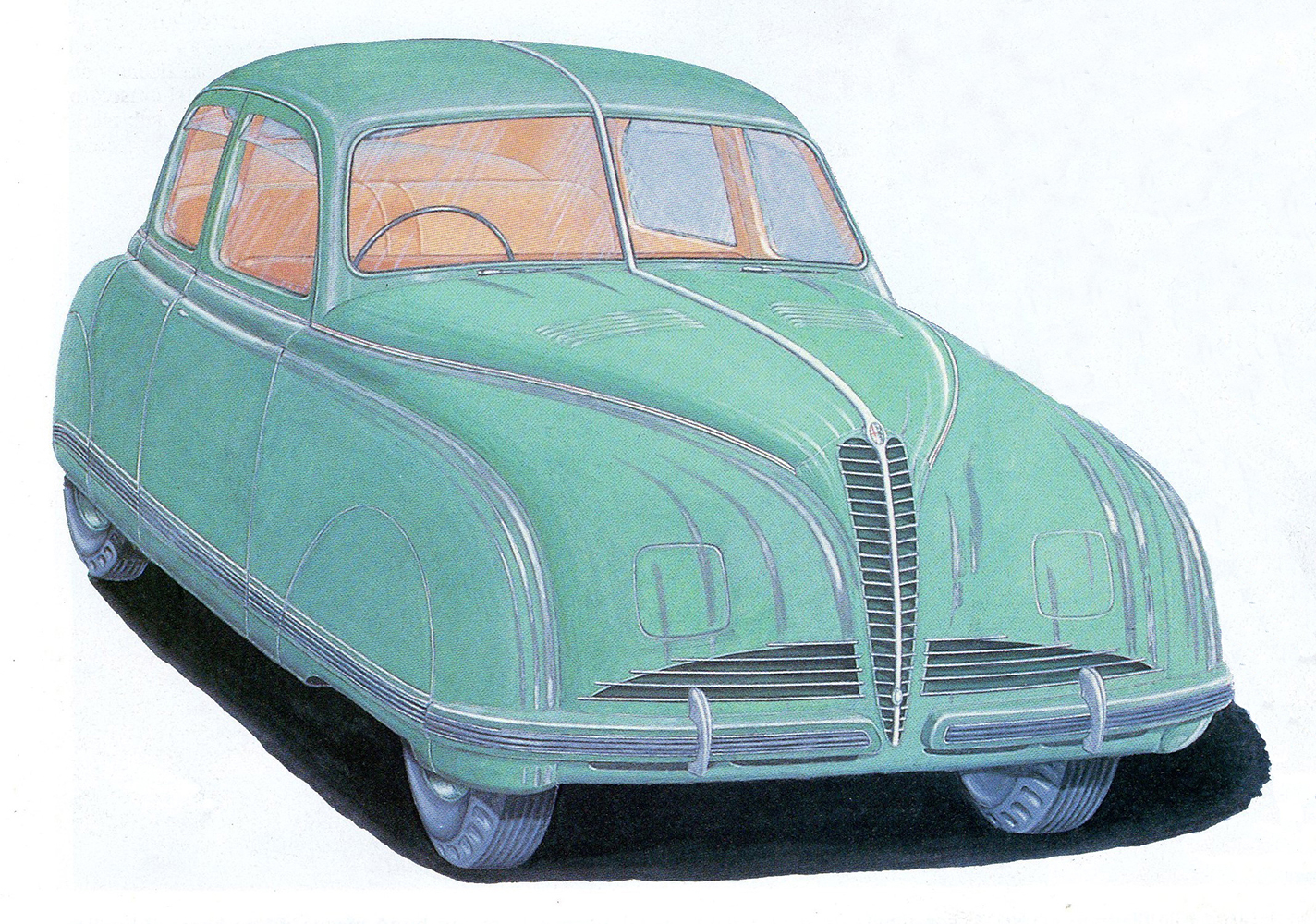

Ricart’s tenure at Alfa is recounted in detail including the now famous tension between Enzo Ferrari and Ricart. Due to comments by Ferrari, it was widely believed that Alfa test driver Attilio Marinoni was killed in 1940 while testing Ricart’s Auto-Union-like rear engine Alfa 512 prototype; Beare finds just enough evidence to support the theory that the car involved in the accident was not the 512, but a special 158 D, modified with an experimental De Dion rear end. And according to Ricart’s son, the truck driver fell asleep and the truck veered into the path of Maronini’s test car. Both the front engine 162 GP project car and the 512 were stopped due to Italy’s entry into WWII. Another project that was put on hold was the Ricart-designed Gazella, a four-door passenger car with either a DOHC six or a SOHC six.

After leaving Alfa in 1945 (read Beare), Ricart had his work cut out for him. It wasn’t until 1948 that CETA (Centro de Estudios Técnicos de Automoción) and ENASA (Empreza Nacional de Autocamiónes Sociedad Anonima) were truly operational and Ricart could look forward to new projects, the first being to upgrade the old Hispano-Suiza 66G (now called the Pegaso Type Z203), giving it a new 9.4 liter diesel engine. The Z403 was a new bus with a monocoque chassis called the “Monocasco”.

The Development of the Pegaso sports car

Beare moves on quickly to detail the rather surprising development of the Pegaso sports car, a project that was established to provide hands-on training for inexperienced technicians, engineers and workers, and to enable his staff to explore new technologies. Unsaid but fairly obvious was Ricart’s passion for high performance automobiles; designing trucks is gratifying but exotic cars so much more exciting. Whether or not there was ever a desire to compete with the products of Ferrari may never be known, but given Ricart’s background of designing and producing hi tech racing machines as early as 1922, Ricart was way ahead of Ferrari in any event.

The oldest known Z102A has an interesting history, having had a 2.5 liter, then two different 2.8 liter engines, then renumbered. It sports a factory ENASA body. Photo by Tim Scott

Technically, the Z102 Ricart Pegaso sports car was initially a DOHC 90 degree aluminum V8 with steel liners, 2472cc both blown and unblown with a five speed transaxle with a de Dion rear end all set in a rigid steel platform chassis. The first engine was completed in November of 1950 and developed 130 hp. Torsion bar springing was used front and rear, the front being wishbone with telescopic shocks. Aside from the first few cars designed and produced by ENASA, the bodies were all created by Touring, Saoutchik, and Serra, a local Spanish firm.

Pegaso nomenclature and upgrades are often complex, and Beare takes us through the changes from the Z102B through the Z103 and the Z104, which was the designation for an entirely new 90 degree V8 with a single came between the banks and short pushrods and increased displacement.

Competition and showcars

There is also a fairly complete chapter on the competition efforts of Pegaso. In Spain, many privately entered Pegasos did well in competitions, but the factory efforts were for the most part embarrassing failures. Crashes at the Panamericana, Le Mans, withdrawals at Monaco’s only sports car race in 1952 had to have made Ricart and Pegaso look bad in light of Ferrari’s victories. In September of 1953, a specially prepared Touring Spyder did manage to take the Belgian flying kilometer sports car record on the Jabbeke highway, at 151 mph, but it was quickly displaced by the Jaguar effort with the XK120M that bested the run by over 20 mph and was well publicized all over the world.

Two lightweight coupes were entered at Monaco in 1952, but multiple problems in practice made Ricart withdraw the entries. Ricart is at the far left. Credit REVS

These failures were somewhat offset but the showcars, including the Thrill, the Cúpula (of which two were produced), and the eye-catching Plexiglas Pegaso shown at the Paris Salon of 1954. Whether clothed by Saoutchik, ENASA, Touring or Serra, Pegasos were always beautiful and the stars of whatever Salon in which they appeared.

But the glory days were all over by October of 1956, though a few cars were built from parts, the factory was no longer interested in making the admittedly costly sports cars.

One last try

Using a Porsche 914 chassis with a Buick V8, Manasian planned to resurrect the Pegaso name. Credit Raffi Manasian

Beare included a chapter on Pegaso re-creations. In the 1980s, Raffi Manasian and his father decided to create a new Pegaso, and almost secured the Pegaso name to produce a small run of fiberglass creations with a rear mounted Buick V8. ENASA, still very much in business building trucks, almost relented until they decided to try a recreation themselves. Manasian gave up the effort while Pegaso recreated the last Serra designed spiders with similar running gear. ENASA quickly gave up on that effort as well after a few prototypes were constructed.

Pegaso decided to create their own replicar in 1990. 10-15 were made with Buick-Rover V8s. Christian Manz collection

In addition to a wide variety of source material, Beare also relies on material from the remarkable book on Ricart Pegaso by Enrique Coma-Cros/Carlos Mosquera (Arcris Ediciones 1988). Beare writes that if you can find a copy, buy it and we agree – it is a fantastic book which covers just about everything Pegaso. The problem is that is it in Spanish only and has never been translated into any other language that we know of.

Do you want this book? Even you can find a copy of that elusive Spanish book on Pegaso and get it translated, David Beare’s two volumes are essential for understanding the evolution of Hispano-Suiza and Pegaso. Don’t even hesitate if you are all interested in either marque. Beare footnotes sources, includes a bibliography but no index.

Where did Ricart die? Where buried?