By Brandes Elitch

Collecting Automotive Books and Literature

In 1982, a British book dealer named Charles Mortimer published a book called The Constant Search, Collecting Motoring and Motorcycling Books. Mortimer started his business during WWII, and spent half a century doing research for this book. At the time, he believed he had chronicled, in 40 different categories, everything published to that date on this subject. In addition to this bibliography, he included chapters on how to start a collection, whether to specialize or not, and how to store and display printed material. Mortimer started at the dawn of the automotive age, so this was an ambitious project. Today, I wonder if it would even be possible to chronicle all the published material on this subject in just the last 30 years. There weren’t a lot of new books about what we call “automobilia” in the sixties and seventies, but starting perhaps 20 years ago there has been a veritable explosion in published material. In this brief article, I would like to touch on some interesting aspects of automotive journalism and book collecting for the car enthusiast. My sense is that almost every car collector has also built up a book, periodical, manual, and literature collection, at least that has been my experience.

In 1982, a British book dealer named Charles Mortimer published a book called The Constant Search, Collecting Motoring and Motorcycling Books. Mortimer started his business during WWII, and spent half a century doing research for this book. At the time, he believed he had chronicled, in 40 different categories, everything published to that date on this subject. In addition to this bibliography, he included chapters on how to start a collection, whether to specialize or not, and how to store and display printed material. Mortimer started at the dawn of the automotive age, so this was an ambitious project. Today, I wonder if it would even be possible to chronicle all the published material on this subject in just the last 30 years. There weren’t a lot of new books about what we call “automobilia” in the sixties and seventies, but starting perhaps 20 years ago there has been a veritable explosion in published material. In this brief article, I would like to touch on some interesting aspects of automotive journalism and book collecting for the car enthusiast. My sense is that almost every car collector has also built up a book, periodical, manual, and literature collection, at least that has been my experience.

he published a motley collection of his archives in something called, Floyd Clymer’s Historical Motor Scrapbook, for the princely sum of $1.50. From this modest beginning, he went on to publish hundreds of books, including the annual Indianapolis 500 yearbook. Clymer should be recognized as the most prolific publisher of the period, and he did a lot to create and foster interest in old cars.

Clymer wasn’t a writer, but in 1946 the first real automotive writer, in the modern sense, made the scene. He started writing for, of all things, Mechanix Illustrated. His name was “Uncle Tom” McCahill. Even today, some 60 years later, he is recognized as one of the innovators of automotive journalism. He wrote six hundred road tests for M.I. and he was a great writer. When I was still in junior high, I would go to the stacks in our local library and read his articles, which mesmerized me, even as a 12 year old. Out of all those cars, his two favorites were, you’ll never guess, the ’53 Bentley Continental, and the ’56-’62 Imperials. He must have had some subliminal influence on me, because somehow I ended up with a 56 and 61 Imperial in my garage, and they’re still there. In those days, my allowance was 25 cents a week, which I spent at our local magazine store on car magazines. There were two publishers then: “Pete” Petersen, who founded Motor Trend, Hot Rod, Sports Car Graphic, and many others, and John Bond, who ran Road & Track. At this point, I want to quote from another pretty influential person in this space, one who came a bit later, when he started a publication called Special Interest Autos, Michael Lamm. Lamm is currently (May, 2012) writing a wonderful series for Hemmings Blog, called, “Cars I’ve Loved and Hated,” and in number 15 of the series, he explains the difference between Bond and Petersen. “Pete was basically a salesman, and Bond was what I’d call an “automotive intellectual,” a car enthusiast with a degree in engineering, and the ability to write. He was a walking encyclopedia of auto facts and trivia, and he had the good sense to join about him people of similar interests…Pete Petersen was more in tune with the audiences he was appealing to…and he could pick good editors.” Lamm points out that in the late forties and early fifties, editors like Bond and Walt Woron at Motor Trend had carte blanche to write about whatever they wanted, and didn’t have to adhere to a formula, unlike the case today.

Click on record to listen to Phil Hill and Road & Track Publisher John Bond. There is a 20 second delay at the start.

In 1953, a Los Angeles attorney wrote a column for Motor Trend, called “Classic Comments.” His name was Robert Gottlieb. He published a book with Hank Bowman called Classic Cars and Antiques, and three years later, another called Classic Cars and Specials. It was Gottlieb who introduced me, and many others, to the idea that certain cars were different and special. Yes, the Classic Car Club of America was started in the early fifties, but it was, in my opinion, Gottlieb who got the word out and popularized the concept. He defined what it meant to be a “classic” car, now trademarked by the CCCA, and is pretty much on the mark even 60 years later. I have been a member of the CCCA for almost 50 years now, and Gottlieb’s vision is as clear and fresh today as it was then. Incidentally, there was one person who was largely responsible for the high quality of the CCCA’s publications. Her name was Beverly Rae Kimes, and she joins the pantheon of illustrious writers and editors in this space.

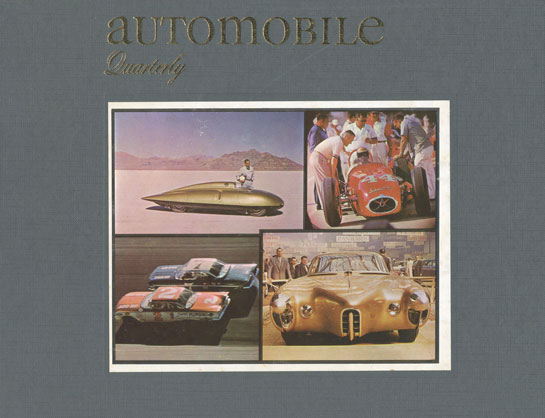

Then, in the spring of 1962, a revolutionary event occurred: a publisher named L. Scott Bailey started publishing a hard cover large format book called Automobile Quarterly. I was still a teenager and I marveled that someone could spend the princely sum of $21 a year for a subscription. Among the first authors were: Ken Purdy, Ralph Stein, John Bond, Denise McCluggage, William Nolan, John Keats, Warren Weith, and Cameron Peck. Bailey wrote in the first edition, “The automobile is an extreme passion with us. As writers, editors, and artists, we have been drivers, racers, and collectors, carrying on a continual love affair with the motorcar. In touring, we have discovered the beauties of the American countryside, in racing, the supreme challenge of speed, in collecting, we relive the great moments of a glorious past.” There was nothing quite like AQ, and I would surmise that every serious automotive enthusiast has at least a partial collection of them over the years. I think that it was AQ that inspired serious American automotive historians, and I would submit that it led, indirectly, to the creation and formation of interest which provided enough momentum to start the Society of Automotive Historians. Indirectly, I think, it inspired Special Interest Autos. I subscribed to SIA from day one, and have every issue, up to the time it was sold to Hemmings. SIA was so powerful a concept that when Hemmings acquired it, they had to split it up into 3 separate publications: one for antiques and vintage cars, one for foreign cars, and one for muscle cars. Lamm can be very proud of what he created.

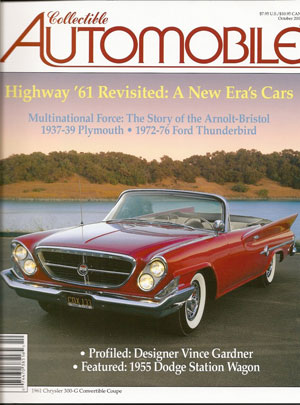

There is another excellent publication called Collectible Automobile, and while I don’t have every issue of that, I have spent many years accumulating a large collection of them, because they are even more in the way of a reference work than even SIA. In fact, when someone asks me for a definitive article on a particular marque or model, I immediately turn to my collection of Collectible Automobile. Last year, one of my friends in France asked me for an article about a specific car, and I had to go to the Hershey swap meet to find a literature vendor who had that particular issue.

In the fifties and sixties, car people read magazines because there were so few new books. Most bookstores didn’t even have a section on automotive books, and there wasn’t a big mail order, catalog provider until Classic Motorbooks came along some time later. When I started working in Manhattan in the early 1970’s, there was one bookstore for all of New York City that sold car books, called Gordons, in midtown. By today’s standards, their selection was not that large, but it was Mecca for car people at the time (along with Le Chanteclair restaurant run by Rene Dreyfus, of course).

There weren’t a lot of books published on automotive subjects in the fifties and sixties. In fact, let’s be honest, there were hardly any, outside of some British books. I remember when a publisher named Dan Post advertised two new books, one called The Classic Cord, and another on the Duesenberg. This was unheard of in the 1960’s, and I remember sending away a five dollar bill for the Cord book (it was ten dollars leather bound, but that seemed extravagant) – a book that I have treasured to this day, even though the Cord was only twenty or so years old at that time, it seemed like it was from another universe, which of course it was. So, in the early 1960’s, there was an emerging consciousness that certain old cars should not be scrapped, but rather preserved and cherished, but it was certainly not a widespread feeling among the American public. I got the idea that my mission in life was to save and restore old cars, and I’m sure I ‘m not the only one with this obsession. As I like to say, “The children come and go, but the cars are forever.” I must have picked up this idea somewhere, probably from something I read. It has been at least partially responsible for more than one failed marriage. In the next column, I will explore the current state of automotive book and literature collecting, including an interview with a well known book dealer. Stay tuned.

Ahh, Tom MeCahill. Loved a number of his extravagant descriptions and answers to readers in the mail to McCahill dept.

I found a few old issues of Mechanix Illustrated in a second hand shop a few years ago and bought them just to read Tom’s articles. Don’t really want them anymore, but can’t seem to just throw them out.

Tom McCahill was really fun; I still remember his description of the ’56 Studebaker Golden Hawk (I had one): “It has the weight distribution of a blackjack.” Back in ’57 when I got my first sportscar I used to buy anything sportycar related–there wasn’t much. Books, models, etc., maybe several a year. I even have such a thing as an autographed print of the LeMans de Cadenet. Now the amount, even from a narrow angle of interest, is huge. The last great buy I found in some hot-roddish magazine: new old stock Dunlop drivers suits for about $20, back in the mid-’80s. Wonder what the backstory was on those!

seems like the automotive world has completely forgotten pioneer p

Calif publisher Dan R, Post who atwars end prodicedbooks on Custom casrs and crested(and wrote) first real book on Duesenberg in 1951, followed by Cord 810 next yr, re-discovering Gordon Buehrig who was forgotten also!..he was a remsrkable man with vision, furthuring careers of a young StrotherMac Minn and Bob Gurr.

Somehow the writer neglected to list John Bentley, a prolific sports car writer of the ’50s and ’60s. He wrote car tests for all of the magazines. But he was the only writer who actually raced those cars. He participated in SCCA races as well as the 12 Hrs of Sebring and the 24 Hrs of Le Mans. I still treasure the gold Omega watch that he and Jack Gordon won at Sebring. I still have his old red Herbert Jonson helmet that he used untill Snell approved helmets were mandatory.

John also wrote racing fiction, but not as well as James Fontana, who you recently reviewed,

Jerry lehrer

Ah, the memories you’ve renewed! I visited Charles Mortimer at his home several times during the early ’70s for old sales literature, and treasure his books. And what wonderful publications we knew in their earliest days; Road & Track, Motor Trend, Automobile Quarterly, SIA, Collectible Automobile.

NYC was a wonderful place to grow up; Inskip’s building on East 64th St. was my mecca. I joined the Classic Car Club of America at the urging of Miss Stein at R. Gordon’s on 59th Street in the early ’60s, when she finally chafed under the task of saving the accumulated issues of The Classic Car mag. during the 10 months a year I was away at college.

I had to print your article to save; eagerly awaiting the next installment!

Still have a reprint of “Uncle Tom’s” MG TC road test for Mechanix Illustrated, in which he teases the driver of a more powerful Buick sedan to try keeping up with him through the twisties…great fun.