Review by Pete Vack

Read review of Vol.I

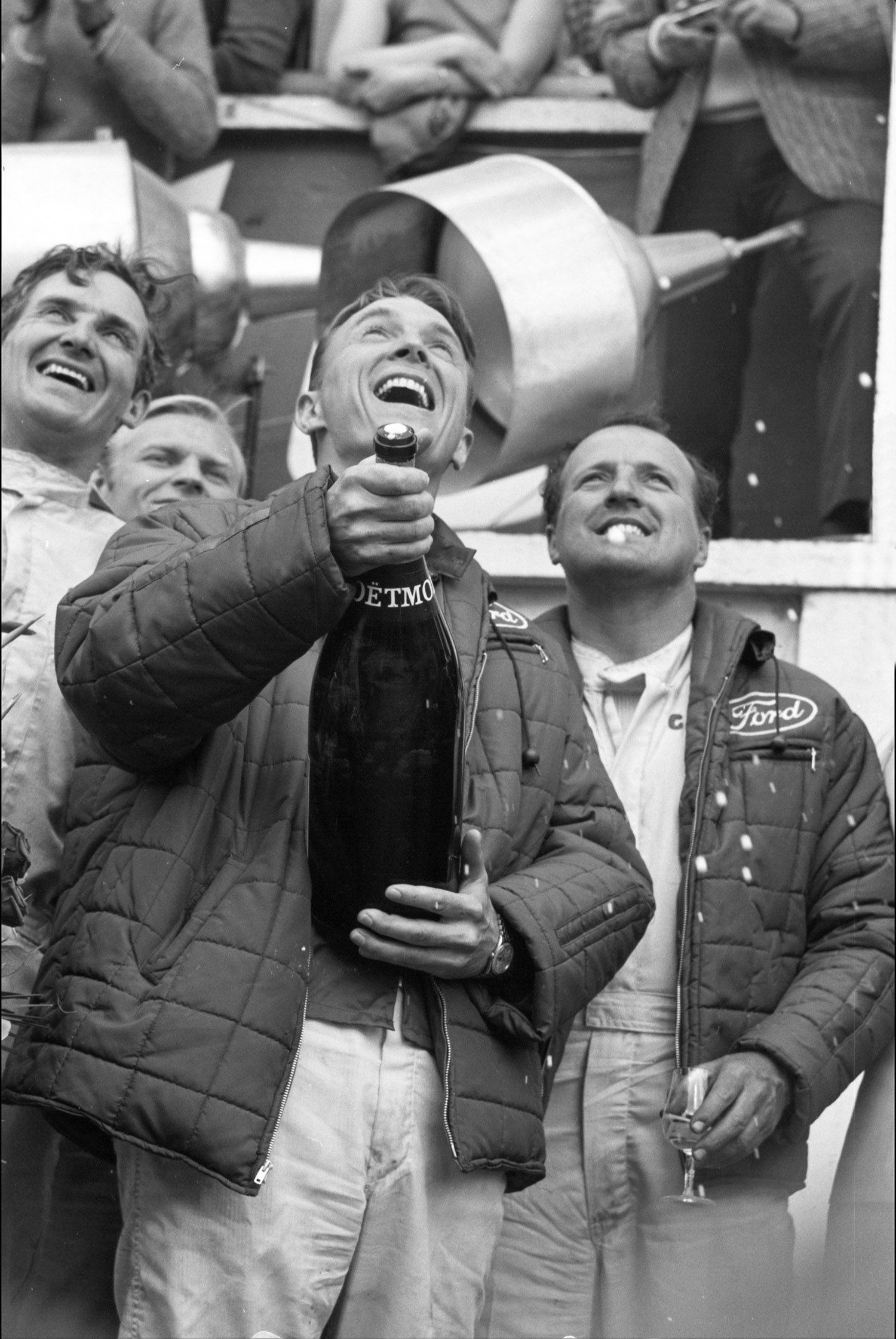

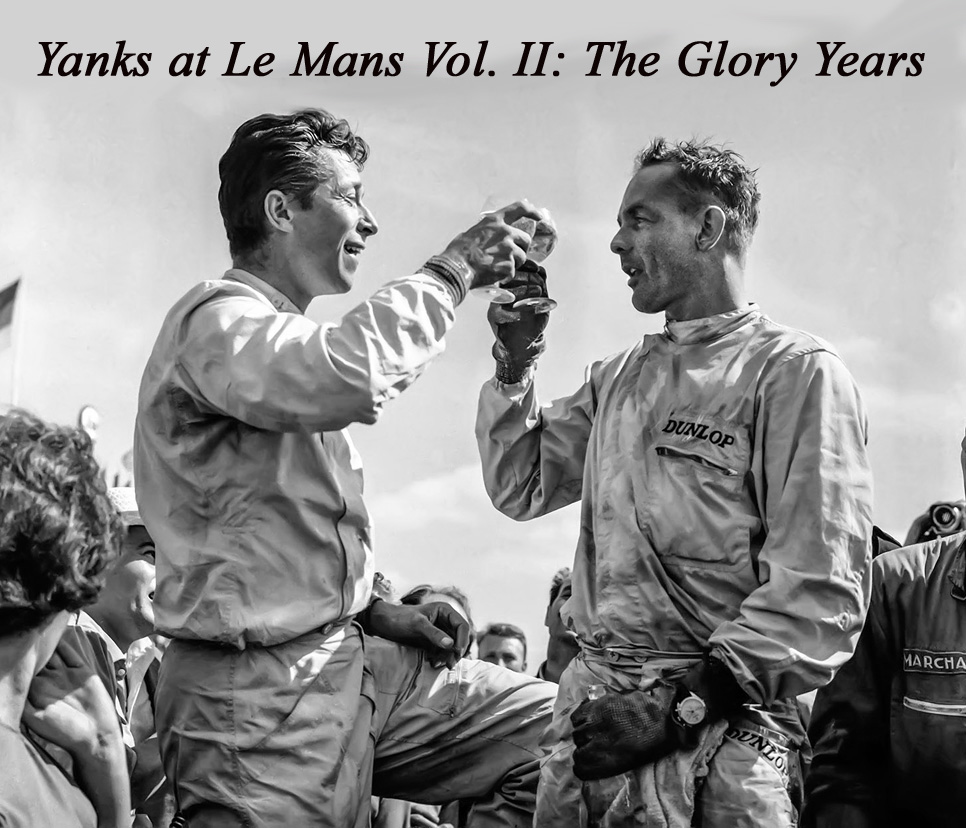

Lead Photo: Hill and Gendebien encapsulates the joy of their third victory at Le Mans in 1962. Gammo-Rapho image.

The 1960s witnessed the peak American participation as well as the greatest American successes at Le Mans. And by 1960, Tim Considine is just getting warmed up to the task. “Between 1960 and 1969, 123 Americans line up to drive in the French Classic, 49 of them for the first time,” writes Considine. But trust us, Tim is up to the job and then some.

We were extremely impressed with Volume I, even though the personal interviews didn’t kick in until the 1950s with the Cunningham team. By Volume II, which covers the years 1960 to 1969, Considine’s skill at getting drivers, mechanics and team members to talk and provide anecdotes shines through the entire book.

However an interview is done, face to face, via email, phone or letter, questioning race team members is not the easiest of tasks. (Tim and I have interviewed some of the same drivers; Tim got more out of them!) Famous drivers have been interviewed so much they usually have a prepared set of answers to any question; the difficulty is to get them to go into more detail. Others have an ax to grind, or have a failing memory. Crew members often see only one side to an issue. Some have their posterity to think about and react accordingly. Considine obviously has the skills and knowledge to sort through this, and the patience and forbearance to keep asking the right questions. He also has to figure out what is true and what is simply BS.

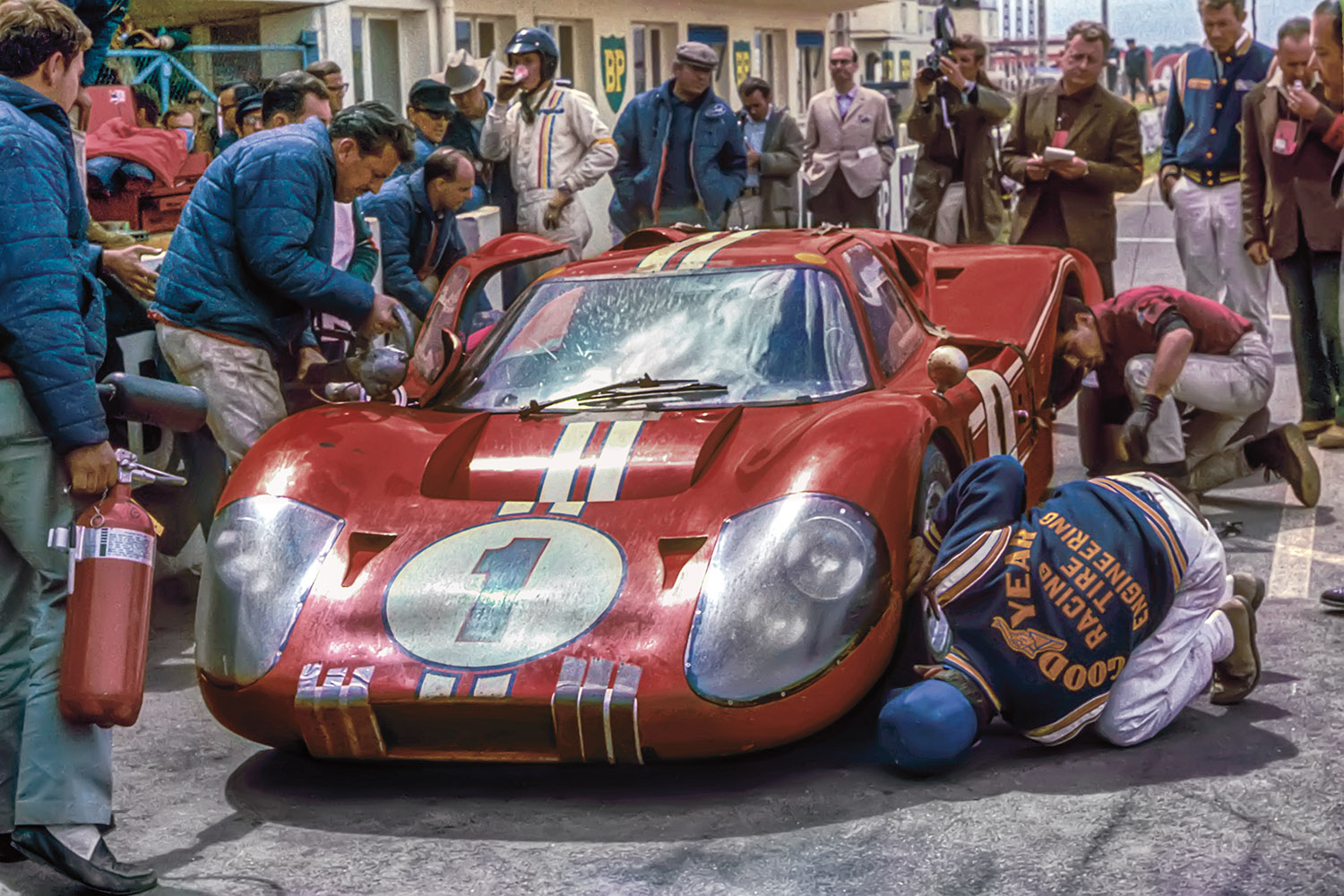

By 1967 Gurney was a Le Mans veteran and guided the Ford MK IV to a win. Here Gurney sips water while calmly waiting for the car to be ready during a pit stop. Considine’s interviews with Foyt, Gurney, Remington and Shelby reveal a great deal about America’s biggest win overseas. Cahier collection photo

In addition to his writing and people skills, Considine knows photography, what shot to use, and where. I asked him why it seems that a good deal of the race photography after the mid-sixties seems – to me, anyway – to lack the drama and impact. I offered that it may be due to combination of things: use of long lens; smaller 35 mm format; very few open cars; larger helmets and face shields; increased uniformity; more restrictions on photographers; streamlining and aerodynamics creating look-alike cars. But that was just my impression. Tim’s answer told me a bit about photography itself, but was also indicative his consummate knowledge, and all-abiding enthusiasm which came through like a flashbulb.

“As to the changes in photography, I wouldn’t say the post ’50s lack drama. But they are different, to be sure, because of the technological changes you cite, but also because the earlier images tell us things with which we are not familiar, and in a way – black and white – that we don’t see things today. We see people we may have only vaguely heard of, the evolution of the car, and importantly, the circuit as it used to be, dirt roads originally, that actually went into the outskirts of the city of Le Mans, and the proximity of the spectators. As a photographer, black and white is less literal and more romantic, I think.

“But for me, that romance continues in the ’60s. My God, look at the spectacular work of Bernard Cahier, Pete Biro and Dave Friedman in the Ford years, and yes, the color now mixed in – maybe lacking the unfamiliarity of black and white, but vivid and an art form of its own, whether from masters like Klementaski or Schlegelmilch, or from talented amateur spectators like Howard Coombs, whose two-page spread introduces the decade. Or then-16-year old Terry Andrews’ dramatic shots that year from the signaling pits of Munaron leaping out of his slowly-rolling Camoradi ‘Birdcage,’ the beginning of the end for Maserati in ’60. Or Gary Fisk’s picture of the entire Cobra team lined up in ’65. Or Sam Posey’s mother’s candid image of her son before starting his first Le Mans, in ’66. Color or black and white, the moment matters. Either can still tell a story. In Yanks, the task has been to keep it personal, and that challenge will no doubt intensify in the next volumes. We don’t just want beautiful long lens car portraits. Sure, we want to see great examples of what they’re driving, but Yanks is primarily about people…Unapologetically, our people.”

In addition to the photography, Tim’s narrative continues to amaze the reader. Volume II is so full of descriptions and stories, it in itself defies description. So here are a few quotes, anecdotes and photos of many that caught our attention.

1960: Fitch and Grossman recalled their 8th place, first in class finish with the Cunningham Corvette, which after losing its coolant, was cooled with ice in the V to allow it to run four more laps to get to the finish. No one was watching the winning Ferraris…at the finish Grossman said the crowds went wild. “I couldn’t get out of the car. They were peering in through the hardtop and wouldn’t let me out of the car. It was so dramatic…”

1961: Augie Pabst and Dick Thompson never gave up with the Cunningham Maserati T63 and finished fourth, Maserati’s best ever result at Le Mans. But they had to change plugs, 24 of them, several times. Maserati was a plug manufacturer and someone got the heat range wrong! Pabst on changing plugs: “There were just little trap doors on each side, so the mechanics had to wrap their arms in wet towels and reach in through the exhaust manifolds to change the plugs. It seemed like hours…”

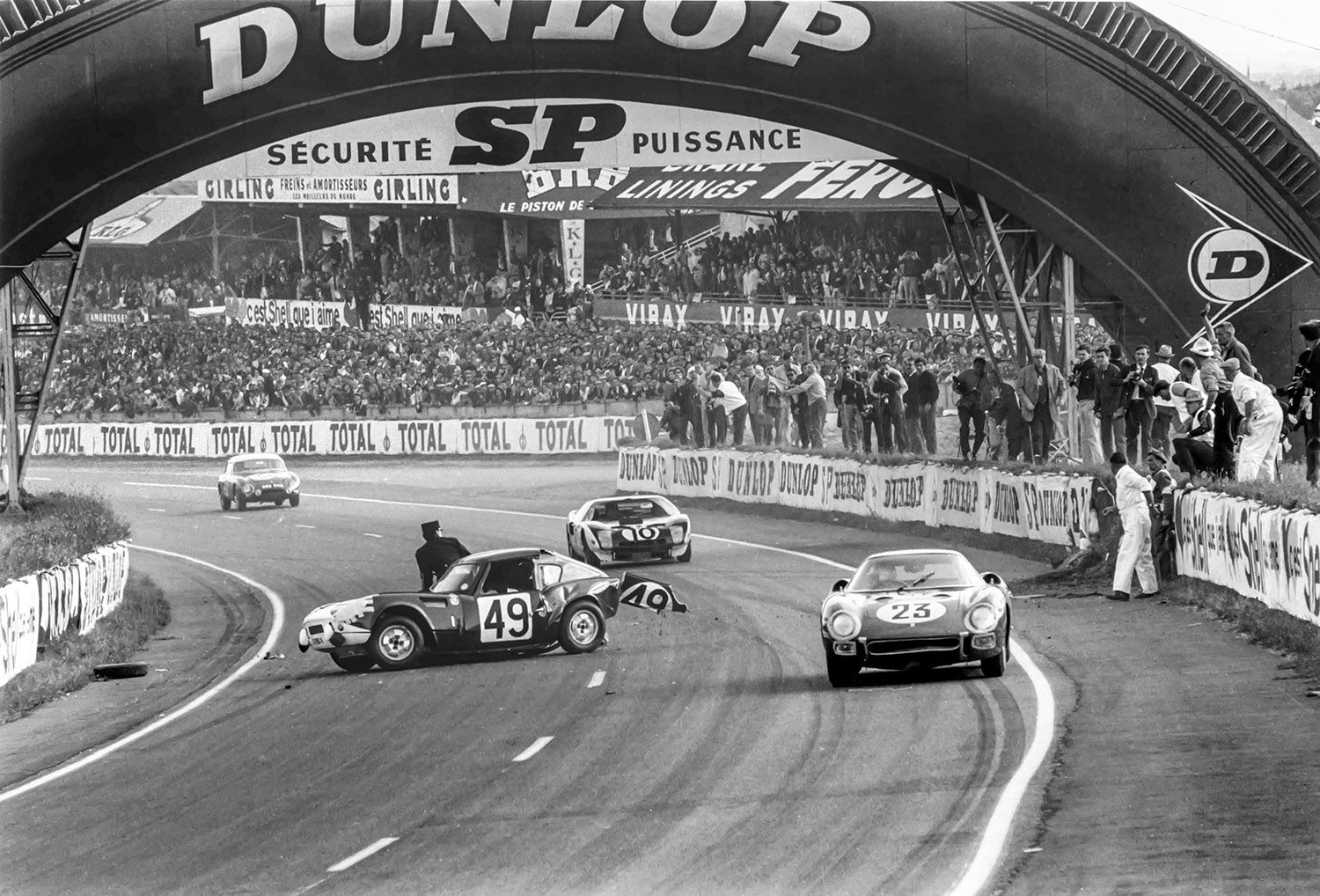

Enroute to a fourth overall, the Maserati of Augie Pabst and Dr. Dick Thompson. Note the small doors behind the driver which allowed mechanics access to the plugs. Klemantaski collection

1962: At the hotel bar, Phil Hill tells GTO driver Fireball Roberts how to negotiate the infamous Kink at night. “Just before the Kink, there’s a big tree on the right. When you pass it, count, one, two, three then turn right a little.” Roberts and Grossman finished 6th overall and first in class.

1963: Noting another great Indy victory this year and his reputation for precision, it was a bit amusing to learn that Penske wasn’t always perfect. In 1963, he teamed with Pedro Rodriquez in a NART Ferrari 330 TR1, and blows it. “I missed a shift,” he admitted. “One of the things that caught me out in that car was that you shifted with the left hand. I think maybe instead of going to third, I went back into first and blew the engine up.”

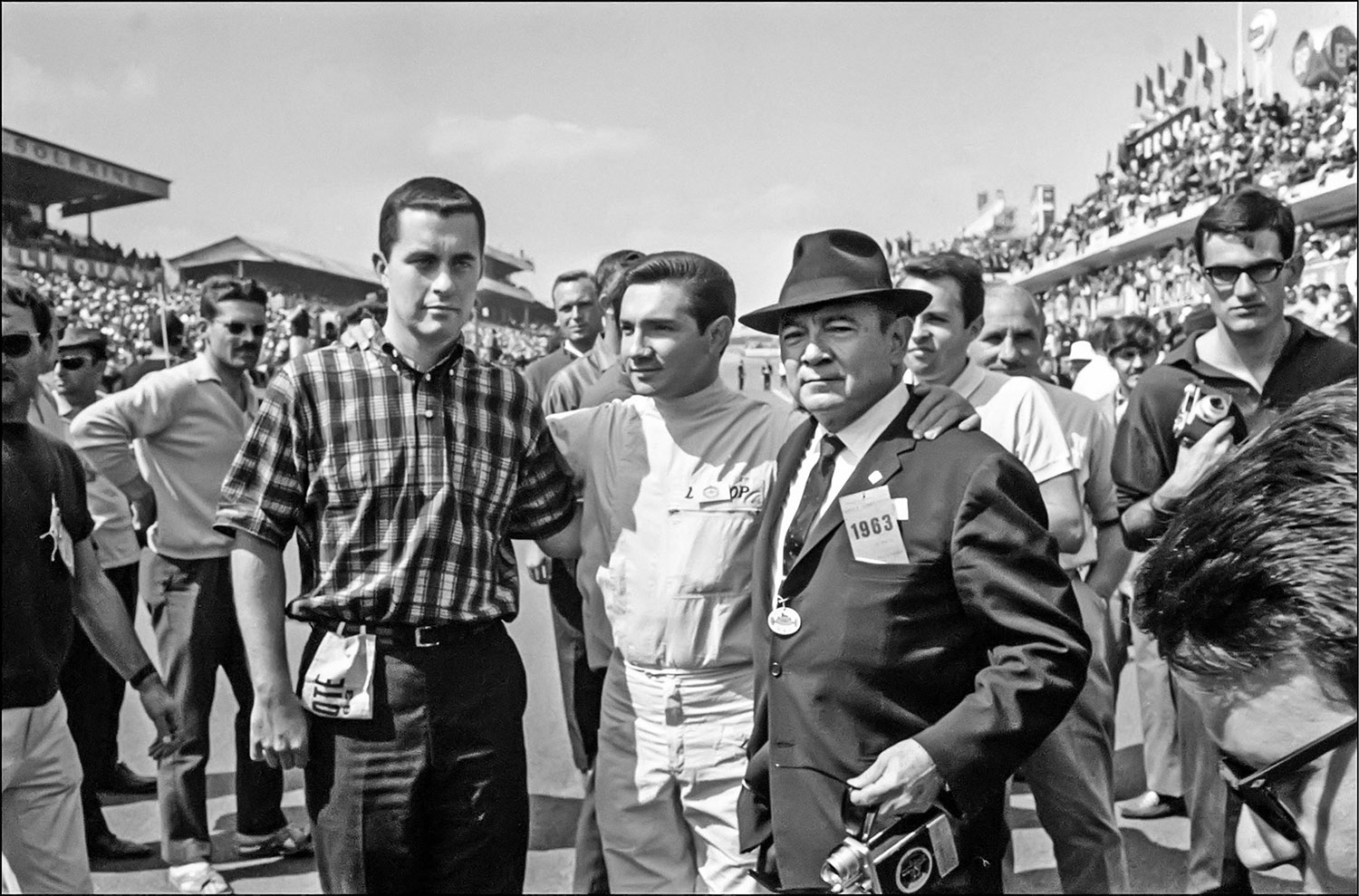

Penske, Pedro Rodriquez with Pedro’s father in 1963. Their ex-Hill/Gendebien NART Ferrari was the 1961 winning car. Gamma-Rapho image

1964: American Mike Rothschild was hurt when he crashed his Triumph Spitfire just before the Esses. The film crew from the movie “A Man and a Woman” was on the scene and filmed Mike being loaded in the ambulance. The scene was used in the movie and further upset Mike’s wife when she saw the movie.

The Rothschild/Tullius Triumph hits the barrier. Tullius: “I couldn’t see what happened. But the caution lights came on and I instinctively knew it was him…” LAT photo

1965: Considine finds three images that tend to support Ed Hugus’ claim that he drove the winning Ferrari at night. One shot of him riding on the front of the Ferrari during the victory lap, another as a gendarme tries to get Ed up on the podium, and a third with the NART team shortly after the victory. Hugus always said that since he was not listed as co-driver, to claim he was might jeopordize the win.

1966: Victory at last but what a mess. The screw up at the finish is analyzed by many of the participants but it still is shrouded in mystery. Most agree that Miles and Hulme got screwed; to make matters worse, Miles lost his life two months later testing one of the new Fords. Shelby: “Ken Miles was way ahead of the race. He would have been the only man in history to win at Daytona, Sebring and Le Mans. He should have won it.”

1967: What was called America’s greatest motorsports victory, ever. All American team of Gurney and Foyt win despite being appointed as the rabbits to force the Ferraris to retire. The MK IV just kept on going like the Energizer Bunny instead. Foyt’s comments are often hilarious; according to Phil Remington, Foyt told his driver to “Get me a couple of them French girls, but I don’t want none of them with hair under their arms.” But at the same time Foyt knew exactly what he had to do to win and did it.

Gurney sprays champagne in what will become a regular event in motor racing. The Henry Ford Collection photo

1968: Enter John Wyer. Out of eight Ford GT40s, Pedro Rodriquez and Lucien Bianchi finished first in the only Ford left in the race. American Porsche exponent Joe Buzzetta was at the Kink when Willy Mairesse had near-fatal crash in a GT40. “I’m going to guess we were in that Kink at about 180 mph, and you had to be off your line to miss the puddle [on the opposite side of the Kink]. And Willy Mairesse, who knew that course better than most people, somehow forgot about it.”

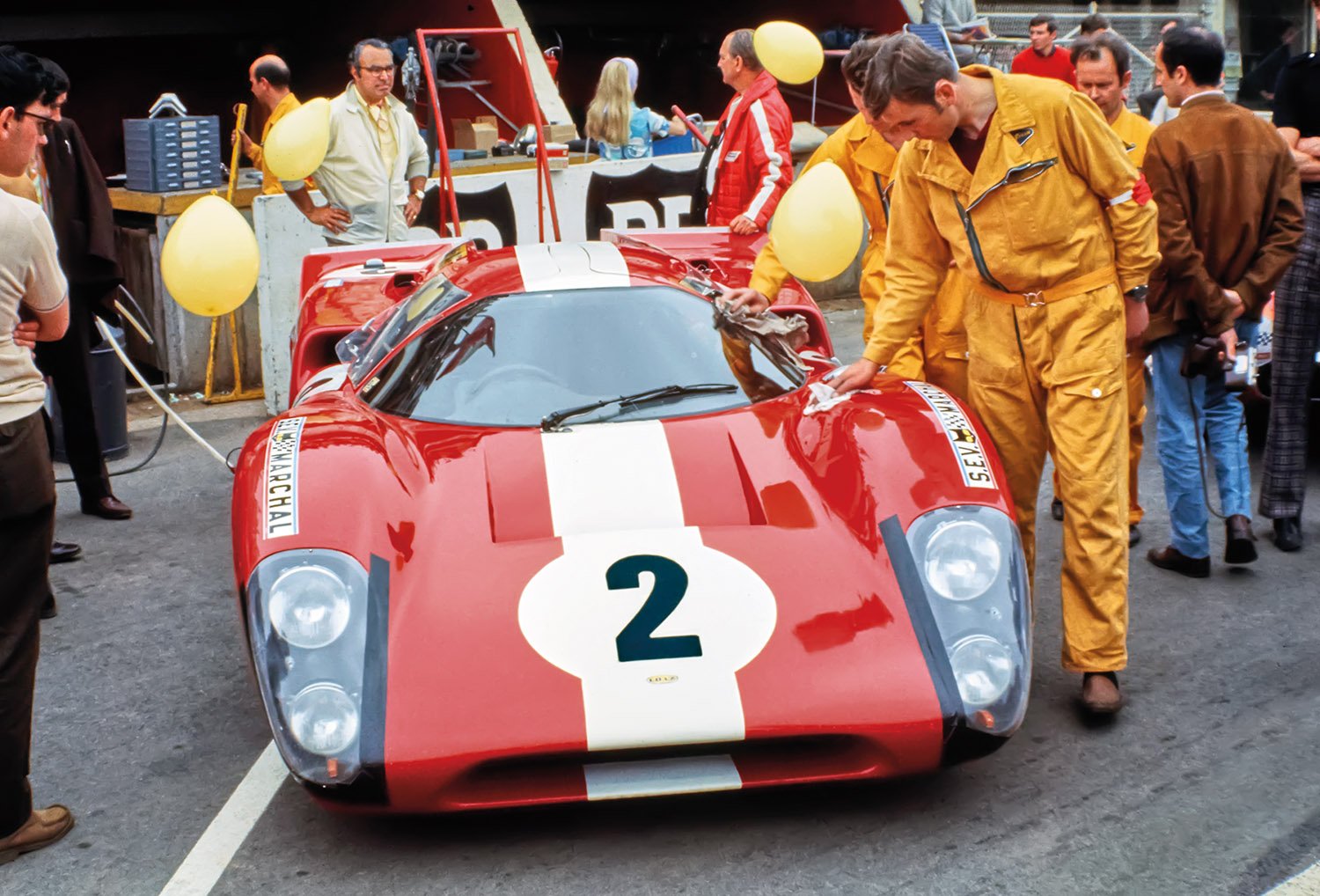

In 1969, Masten Gregory was making his 13th appearance at Le Mans, driving this lovely Lola. Gregory drove at Le Mans more than any other American driver. REVS Institute photo

1969: Ford wins but the Germans are coming. From a high of 25 drivers in 1960, by 1969 there were only two American drivers at Le Mans. But the John Wyer GT40s lived on for another year as Jacky Ickx out drove the Hans Hermann Porsche 908 to win the closest unplanned finish at Le Mans to date. But Sam Posey drove the 1965-winning NART Ferrari 275 LM and finished 8th overall with David Hobbs. “That car was unstoppable,” laughed Posey. “It’s in the museum at Indianapolis now, and you could probably roll it out and do another 24 hours.”

Twice Around The Clock – The Yanks At Le Mans Vol. I-III

Author: Tim Considine

Publication Date: October, 2018

ISBN: 978-0-9993953-0-1

Page Size: 9 x 11 inches

Three volumes, hard cover in slipcase

Vol. I (1923 – 1959): 408 pages / 371 photographs

Vol. II (1960 – 1969): 360 pages / 327 photographs

Vol. III (1970 – 1979): 328 pages / 227 photographs

Note! If you want an autographed copy, request one from the CONTACT button, which goes straight to Considine.

Next week we’ll review Volume III.

Good Morning!

I must compliment you on your praise of Tim Considine’s “Yanks” …

And, If I may … add a bit of an “upgrade” to the news that the book was the Motor Press Guild’s pick as “Best Book of 2018”, which is correct.

The book was further honored with the singular Dean Batchelor Award for Journalistic Excellence for 2018.

THANK YOU!

Doug Stokes

2018 Chair- Motor Press Guild Dean Batchelor Awards

Here is the link to the review of Volume I…

https://velocetoday.com/twice-around-the-clock-the-yanks-at-le-mans/

Pete