January 3rd 2007

Photo by Alessandro Gerelli.

|

Story by Pete Vack

Before we begin down this long and winding road, allow us to remark that we are well aware of the various contributions to the classic Grand Touring car which came from countries like Great Britain, France, Germany, and even Czechoslovakia. Italy was most certainly not alone in the development of the genre.

Grand Touring. GT. Gran Turismo. GTA, GTB, GTC, GTE, GTI, GTL, GTM, GTO, GTP, GTR, GTS, GTV, GTX, GTZ. There is no doubt a �GTSUV� out there of which we are blissfully unaware.

No other automotive adjective has ever been the victim of such repeated assaults upon its meaning. Originally, though we don�t know exactly when, where or by whom, the definition of a Grand Touring car was �a road going lightweight semi-luxurious coupe built on a high performance chassis.�

The concept of a lightweight coupe stretched tightly over a powerful short wheelbase chassis evolved in the mid 1920s as independent coachbuilders adopted the �aerodynamic� forms to road going cars, sensing that the increase in total frontal area and increased weight might be overcome with a streamlined shape.

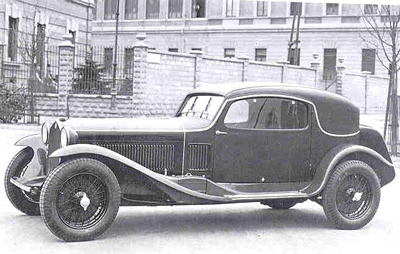

This 1932 Weymann Touring Alfa 2.3 won the closed car catagory and placed a remarkable 4th overall in the Mille Miglia. Note the dull body and straight panels.

|

Construction techniques

Unthinkable to us now, in the pre war years, car chassis were extremely flexible. In fact, the chassis itself was considered part of the suspension, and allowed to visibly move around corners and over bumps. Building a rigid body upon such a structure was possible but very heavy and costly. The answer to the flexible flyer problem was, for a while resolved by a Frenchman by the name of Charles Torres Weymann, who worked out a way to allow a body frame made of wood and leather (or leatherette) to flex without coming apart at the seams. So good was his technique that the closed car became much easier and more reliable to produce. One can easily tell a Weymann bodied car: nearly straight panels with a dull finish. The Weymann patent was used throughout the world from the early 1920s to the late 1930s, including an Italian shop by the name of Touring.

The Superleggera framework (1936-37) was both flexible but light, as can be seen here. The technique was perfect for competition and small production companies.

|

Touring made maximum use of the Weymann patent and construction technique, but gradually began to experiment using metal in place of the wood and fabric. By 1937, chassis design now often incorporated independent front suspension and less often, independent rear suspension. The frame became stiffer as a result. At the same time, Touring introduced his �Superleggera construction�. On a more rigid platform, a series of tubes along the shape (now convex and concave at will) of the body were welded to the chassis, and over that aluminum panels were tacked or tucked over some of the tubes. There was still flexibility; the tubing underneath could move slightly while the overlying aluminum panels remained fixed. The entire structure was extremely light weight.

For the first time cars could have complex curves over the entire surface area of the body and a remarkable change swept throughout the automotive industry (save MG and Morgan). We and we hasten to add that the Budd Steel body stampings were, if anything, even more responsible for this revolution in complex curves particularly as applied to mass production.

This technique was applied to spiders and open cars, but the effect on the coupe was much more impressive.

The sun was rising on day of the Grand Touring car.

Grand Touring racing activity

While a Grand Touring car should have been ideal for Le Mans, given the regulations which always sided with stock configurations, a very long straight and the length of the event, a coupe did not win at the French classic until Mercedes Benz did the trick in 1952 with their 300SL cpupes. Ironically, the 300SL Gullwing in production form was to be the instigator to the rapid development of Ferrari GT cars, the 250GT in particular.

One of the Grandest Touring cars ever. The 250GT Tour de France was hastened to life by the successes of the Mercedes Benz 300SL Gullwing. Photo by Alessandro Gerelli.

|

The Mille Miglia, on the other hand, openly encouraged closed cars beginning in 1930, when a class for �Touring cars� was established. In 1931, a closed �semi rigid� Touring bodied Alfa 1750 GT was among several entered in the race. The team of Gazzabini and Guatta won the closed cars class and placed 8th overall. In 1932, driving a 2.3 Alfa Touring saloon, Minoia and Balestrero not only won the closed coupe class but placed 4th overall. It was to be a harbinger of things to come, for closed cars, gradually called �Grand Tourers�, would win five of the next 18 events.

The 2300 Alfa Pescara, a car now rarely remembered, was a favorite for the Touring lightweight Superleggera process. Photo by Alessandro Gerelli.

|

By the middle of the 1930s, coupes, large and small, made their appearance on the streets and circuits of the world. The list included Adler in Germany, Talbot and Bugatti in France, and the famed Embricos Bentleys in England/ In Italy, Lancia, Alfa, Fiat and Siata were all donning a top by way of Pininfarina, Touring, Farina, and others save the most famous coupe maker of all, Zagato, who didn�t really get into the act until after the Second World War. Some were little else than spiders with a tin top attached, others, like the delightful cars which rolled out of the factory now called �Superleggera Touring�, were luxurious even when designed for racing only.

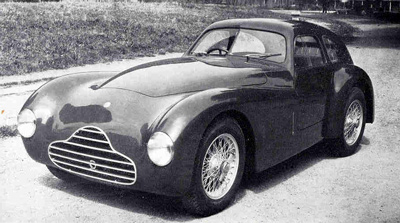

Another rare Alfa is this 2500 SS. It was Alfa's first postwar competition car and as a coupe won the 1950 Targa Florio.

|

Among the first foreigners to take advantage of the Superleggera construction was BMW, who had Touring design and build a competition spider and coupe for the Mille Miglia. They promptly won the shortened 1940 event with a coupe, thus becoming the first closed car to win the Mille Miglia. After the war, the event was again to last for one thousand miles, and a pre war Alfa 2.9 Touring coupe driven by Biondetti in 1947 was the winner. Biondetti won again in a Allemano bodied Ferrari coupe in 1948. Marzotto�s �business suite� victory in 1950 was made possible with a 166MM Ferrari, and the next year Villoresi won with a 4.1 Ferrari Vignale coupe. The last coupe to win the Mille Miglia was the 212 Ferrari Vignale coupe of Bracco in 1952. Notably, not one of these cars ever had the script �Grand Touring�, �GT� or �Gran Turismo� attached to any part of the body.

As at Le Mans, coupes missed the mark at the Targa Florio, the world� oldest motor race. It was not until 1950 that a coupe--still not called a �GT� won the 34th Targa Florio. And a rare car it was, too, being a hybrid Alfa Romeo 2500 SS Tipo MM, which in the hands of the brothers Bornigia, easily won the event.

The first car to be called a "Grand Touring" car by the factory. Unfortunately they did not

use the GT nomenclature as part of the body trim. That would be done by Studebaker. Oh well.

|

The first postwar car, and arguably the first car ever to be properly called a �GT� was the Lancia B20 Aurelia, a nomenclature which it heartily deserved by winning outright the Targa Florio of 1952. And a coupe it was.

Yet, there was no script on the famous Lancia declaring its GT heritage. That small victory would be claimed by an unlikely car, the Studebaker Golden Hawk.

Next time, folks.