January 31st, 2007

Italy in the Era of the Appia

Part I of IV

By Lorenzo Marchesini

Original Lancia brochure for the Series I shows a happy scene in post war Italy.

|

The history of the Lancia Appia can be used to epitomize the struggle and success of one of Italy�s oldest car manufacturers in the aftermath of World War II, as well as to illustrate life of the Italian motorist during the challenging times that preceded the �Economic Miracle� of the Sixties and the �Economic Boom� of the early Seventies.

Post War Recovery

The Lancia Appia line of cars was born in 1953 at a time when Italy was still far from having overcome the devastating impact of World War II. With assistance from the Marshall Plan, the country's fledgling economy experienced a somewhat hasty reconstruction. The benefits of this reconstruction had however not yet reached the population at large. The country still faced critical shortages, while unemployment was still rampantly high. The ravages of World War II were evident everywhere, and many Italians, fearful of the communist threat, had moved abroad in search of a better future. Nevertheless, the Italian automobile industry was recovering and major car manufacturers � such as FIAT, Alfa Romeo and Lancia - had by then imported tooling equipment and technology from the USA and looked with great expectations to the future.

Italian automobile production grew rapidly from 217,000 vehicles in 1954 to about

269,000 in 1955, and was projected to attain 300,000 units in 1956. Exports rose even stronger from 40,800 units in 1954 to 70,000 units in 1955; major export markets were Germany and Austria, followed at a distance by Switzerland, Belgium and Sweden. Most remarkably exports to both Malaysia and India reached 3000 thousand cars, while the exports to the USA in 1954 were accounted for as part of the exports to the rest of the world and were in volume by far less than even the 1100 units exported to Portugal.

Domestic car population

Not surprisingly, about 85 percent of the cars produced in Italy were, in the mid-Fifties, destined for the home market where the Italian car manufacturers benefited in those days, and for many years to come, from a highly protective regime of import duties which were set at 45 percent of import value on foreign made cars with an engine of displacements less than 1.5 liters, and 35 percent of such value for vehicles with engines exceeding 1.5 liters.

By the mid Fifties the country had a relative small but nevertheless rapidly growing car population that went from 3.4 million vehicles in 1954 to about 4.1 million vehicles in 1955; by the latter year experts projected the number would further increase to 4.9 million vehicles in 1956, or by about 20 percent!

In 1946 Italy had a density of one car for every 305 inhabitants, whereas in 1950 there were 138 inhabitants per car; car densities further �improved� to one car per 57 inhabitants in 1955 and to 26 persons per car by the year 1960. While this growth was impressive, it must be stated that it lagged far behind the densities of other countries; in 1960 the USA had on average one car per 3 inhabitants, France and the United Kingdom 9 each, and Switzerland 10. It can also be stated that the Italian car density was, in 1960, at the same level of that of Singapore.

The Via Appia, the Roman road from which the new Lancia borrowed its name.

|

Road and Highway construction

The growing car population exacerbated the problem of an inadequate road network. By the end of World War II Italy had a small network of highways (�Autostrade�) that totaled 506 kilometers (a mere 320 miles) in length. Among these was the Milano-Laghi highway that connected the outskirts of Milan to the Lake District that borders Switzerland; built in 1925, the Milano-Laghi was the world�s first highway. Expansion, however, continued at a slow pace. By the mid Fifties only an additional 44 kilometers (about 30 miles) of highway were added by connecting the coastal cities of Genoa and Savona.

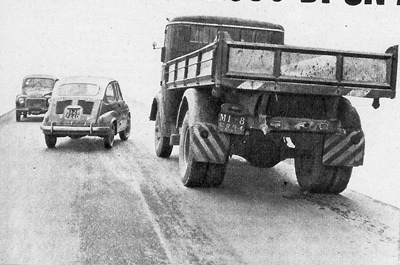

A Fiat 600 narrowly completes a dangerous pass on the roads of Italy in the mid Fifties.

|

The national network of highways was very unevenly distributed over the country�s territory. Only 40 kilometers (or 25 miles) of highway ran from Naples to Pompeii in Southern Italy, and about 20 kilometers (only about 15 miles) from Rome to Ostia in what is known as Central Italy; all of the remainder, and thus 490 kilometers (about 310 miles) were found in Northern Italy, essentially along two axis, one covering Turin-Milan-Padua-Mestre (near Venice), and the other covering Milan-Genoa-Savona; the Firenze-Mare (or Florence-Sea) highway did not connect to any of these two axis.

However, the county availed from an extensive network of roads (�Strade Statale� (or S.S.) for State Roads and �Strade Provinciali� for provincial roads). The origins of S.S. roads such as the Via Flaminia, the Via Aurelia, and the Via Appia dates back to the days of the Roman Empire; it is the names of these roads that were used for the Lancia passenger car models of the Fifties. Traffic on the �Statales� and �Provinciales� was very intense, particularly in the Fifties. A prime example of a �Statale� is the Via Emilia, a road that played a magic role in the Mille Miglia public road-racing event and that runs, essentially in East-West direction, from Milan all the way to Adriatic coast.

Road accidents

Those who used roads other than the highways traveled at highly differing speeds, in a fashion that is much similarly found in today�s traffic on major roads in Africa, Asia, or Latin America. This, and the passion that Italians have for road racing on public roads (each village seemed to have its own Mille Miglia hero along with a local race event) led to many spectacular and often-times fatal accidents. The number of annual road accidents increased rapidly from about 54 thousand in 1951 to roughly 126 thousand in 1954; during the same four years the number of deaths by traffic accident increased from three thousand to more than five thousand and the number of injured people more than doubled from 42 thousand in 1951 to 99 thousand in 1954. These figures meant that by 1954 an accident happened on average every four minutes, that 15.6 people died due to traffic accidents while 274.3 were wounded on an average day; put differently, on average one person died every 90 minutes whereas one person was wounded in traffic on average every five minutes. Expressed per vehicle this meant that annually one out of every 8 vehicles would get involved in a traffic accident, that one fatal injury occurred per 205 vehicles, and that one person was injured per 11 vehicles.

Accidents reached epic proportions in the 1960s. The new auto magazine "Quattroroute", where this photo was found, would publish many such images as warnings to Italy's new drivers.

|

The number of traffic accidents reached epidemic proportions in the second half of the Fifties as Italy slowly but steadily started the process of mass motorization, early on by using the scooter and later on - when FIAT�s 600 and 500 became increasingly popular - by using the car. By then it was not uncommon the see entire families (father, mother and 2 or 3 children) on Vespas and Lambrettas (a practice less common with motor bicycle riders). The �lucky� ones traveled by car, usually cramped (5 or 6 people per car were the rule rather than the exception) and with bulging luggage placed on roof racks, while food and wines were stowed in every nook and corner of the cars.

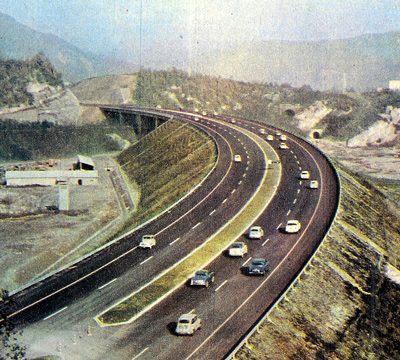

Autostradas relieve congestion

The road network and traffic situation much improved by the late Fifties, at a time when Government completed a great number of important infrastructure projects in the roads sector, such as the �Autostrada del Sole� (literally the �Highway of the Sun�) that covered a 200 kilometers (125 miles) Milan-Bologna section. The new Autostrada alleviated traffic on the Via Emilia, which had the most spectacular 100 plus scenic kilometers (65 miles) of highway between Bologna and Florence and allowed to reach Florence without having to climb the famous �Passo della Futa�. It was a drive that gained respect as a daunting mountain section of the Mille Miglia race.

The Autostrada borrowed heavily from the German Autobahns and alleviated a great deal of congestion, particularly in northern Italy.

|

The high cost of driving

Owning and operating any car was a costly affair in the Italy of the early to mid-Fifties. Italians had to face gas prices that were among the highest in Europe (special discount coupons were made available to attract tourists). Moreover in those years the per capita incomes were certainly not among the highest in comparison to other industrialized countries. Hence, all but a relatively few affluent people � mostly living in the urban areas - could afford to use the toll-highways or to buy a new car. Tax laws further assured that Italian automobile manufacturers dominated the national small-car market. Traffic on roads other than the highways would for many years consist of a mix of trucks, lorries, buses, passenger cars and pick-ups, bicycles, motorcycles and pedestrians, as well as carts that were pulled by a mule or a horse. Driving safely on the non-highways was highly complicated by numerous town centers and the great number of railway crossings.

Back roads, however, continued to be filled with a variety of transportation devices.

|

A cottage industry of speed

Up to the late-Fifties the Italian national car population comprised large amounts of prewar trucks and other vehicles that, with a disproportional optimism were kept running �ad infinitum� by the �master� mechanics and their apprentices with parts sourced from junkyards or else modified mechanically in a fashion that would be described as �tuning.� These "tuners" comprised a thriving cottage industry where skilled artisans earned a living by transforming prewar FIAT Balillas and 1100s passenger cars into pick-up trucks and the occasional �special.� Many of these mechanics and �coach builders� would also become famous for their �Etceterinis�. Stanguellini in Modena and Bandini in Forli are but two examples of this genre. There were many speed shops (in the North at least one per village) where a local master mechanic-cum-amateur race car driver specialized in �elaborazioni� (or car tuning) thus providing his clientele with power enhancing upgrades such as free flowing exhaust systems, modified heads and oil pans, as well as enlarged carburetors and the multi-tone series of air horns.

Such was the economics and state of the automobile when, in 1953, the Lancia Appia was introduced. The Appia would provide a generation of middle class Italians with a solid, reliable, somewhat luxurious and practical automobile for the next ten years.

Next: The Appia Series I