Story and photos by Paul Wilson

Those breaking-wave fins are the feature that I love best about BAT 7, and with just minor changes, I wanted similar ones on my BAT. For better side vision, mine would rise from slightly further back. I don’t think that large slot in the tall areas has enough thematic connection with the overall design. And on the sides, did I want the crease extending back from the top fender line to fully disappear, as it does on BAT 7, or continue all the way to the rear? Yet again, I had the rare advantage of being both the designer and fabricator. I could make up something, see if I liked it, and change it if I thought it could be improved.

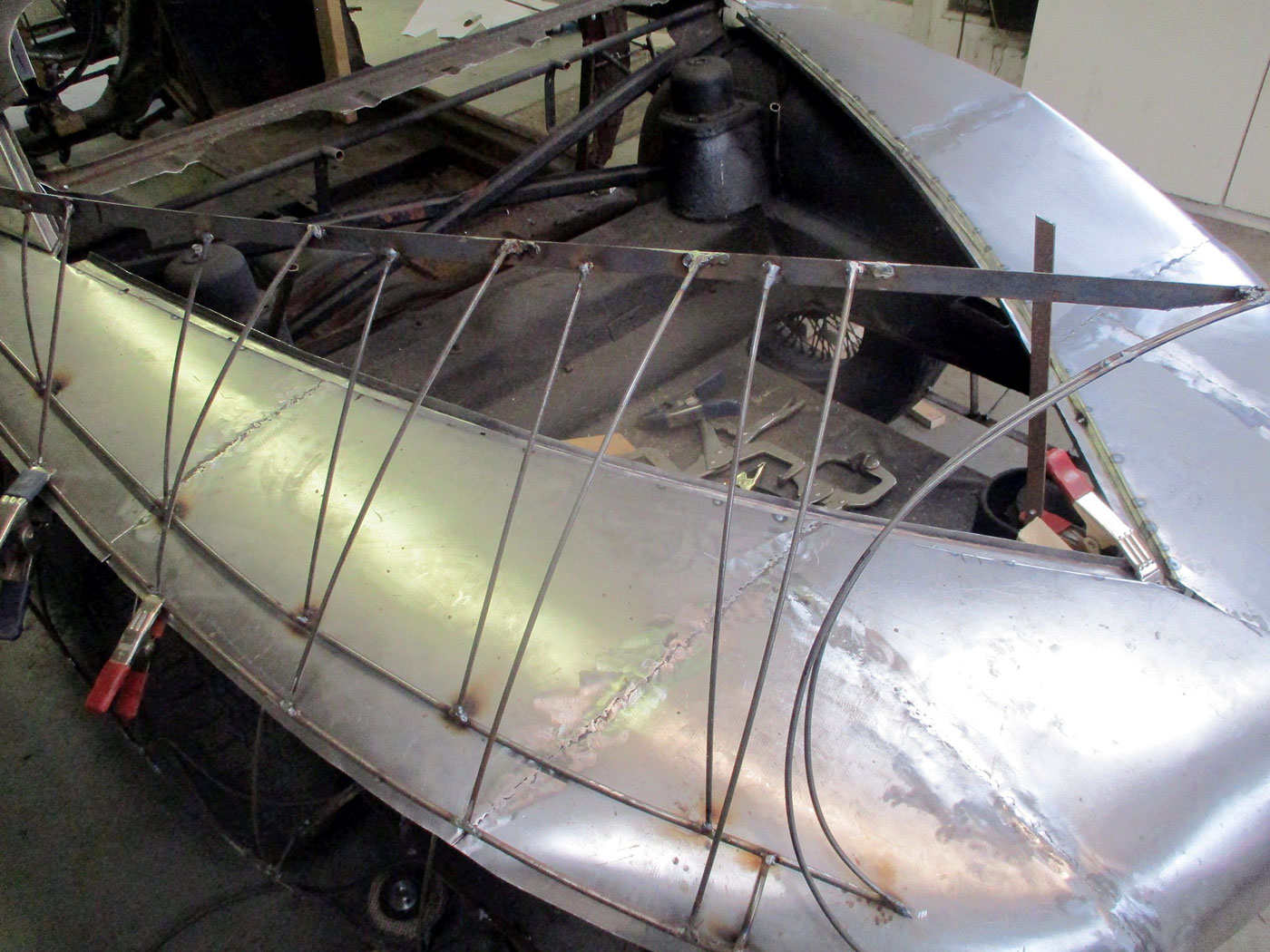

Making a wire form was easier than expected–on the first side, anyway–when I discovered that the top line wasn’t free-formed, but curved in just two dimensions. Think about it: a yardstick, placed at a slight inward angle, would align with the peak of one of BAT 7’s fins: on a near-horizontal plane, it’s a straight line. So instead of a round rod, I made the top rib with a flat piece of steel stock that bent easily only for the inward sweep, but was rigid in the vertical direction. Very soon I made a frame that duplicated that long curve exactly.

Most of the sheet metal is nearly flat, so just a little stretching on the English wheel (in the middle) or shrinking at the edges was all it took to make it fit. The top of each piece could be bent over the frame, holding it more conveniently and accurately than spring clips.

Very quickly, the fin took shape. By now, though, I’d learned a hard lesson about metalwork: rapid progress is always an illusion. A difficult and time-consuming job is always lying in wait. I foresaw at least two of these.

First, the back of the fin had one curve when viewed from the side, another when seen from the rear. At the bottom, it blended into the fender shape. And it was, itself, slightly rounded. Making this area was going to be hard enough; making a perfect match on the other side . . . I didn’t want to think about that. A second problem was the fit to the fender, on the bottom. The fin is six feet long (nearly two meters). Making it touch the body over that huge length would be hard. And what if, in attaching the outside, I needed to adjust the angle slightly? The whole inner seam would open. I had to redo both of these problem areas several times.

BAT 7 has large slots in each fin, parallelograms that lean forward. Like so many BAT features, they were supposed to have some aerodynamic function, but I suspect that design, not science, occupied Scaglione’s mind when he added them: they give a welcome accent to an otherwise bland area. However, their square corners conflict with the theme of smooth air flow, and shouldn’t they lean back, in sympathy with that dramatic line above them?

I tried that solution, but didn’t like it any better than the original.

OK, how about a crescent shaped like a new moon? Maybe with an inner duct, carrying the air outwards? I had lots of ideas. But all, in the end, were rejected. I didn’t want to draw attention from the fins themselves. If a square slot pleased Scaglione in 1954, a small modification was all I felt I could do. My final version follows the curve at the back of the fin, but otherwise is much like the originals.

From the beginning, I realized that exact symmetry was critical in construction of the fins and rear area. If one front fender wasn’t exactly like the other, the difference would be hard to spot. Not so in the rear, where the lines of the fins and hatch were so easily compared, side to side. When the hatch was opened, the fin tips had to clear it by precisely the same thumb’s width.

And the fin contours, especially at the rear, were complex: their curves change as the viewer moves around them. I did my best to make the second fin’s framework match the first, but it’s not perfect. Here’s where modern CAD methods do better. But my rule is that my BAT must be built just as the originals were–same materials, design environment, and construction methods. I’ll bet the hand-made originals weren’t perfect, either.

At this point, for the first time, I had enough of the car built that I could see what it would look like as a whole. Nearly every day for seven months I’d added this piece or that, but inside my shop I got only a closeup view. Now came the test: when I moved it outside and viewed it at a distance, would it come together as I’d imagined it? I think it looks promising.

After a years-long delay, mechanical parts for my 6C2500 coupe have arrived. So I’m setting aside construction of the BAT for a while. I would love to be able to report on the completion of one, maybe both, of the 6C2500s before too long. Wish me luck–it’s the key ingredient in all these projects, and too often lacking.

Hello, I owned this car I bought from Joe Pasak in South Bend Indiana it was in his basement.. He sold it for us and got a Porsche 911 and some cash

It’s really looking great. A question which I have is whether the wire armature/buck is left inside the fender?

Ben,

Actually the whole wire frame comes out. I have to be careful not to make shapes that make this impossible, but with the fins it worked fine. I took it out before closing up the back. The fenders don’t need any extra strength–the contours make them very stiff.

Paul